The Man Who Haunted Himself (1970) appeared as part of new British production strategy. In fact, the British had been trying to dominate the global film industry since the silent era when the population of its Commonwealth exceeded that of the United States. At various points, the British had launched various distribution attacks on Hollywood – aligning with U.S. cinema chains, organizing their own distribution system (Gaumont-British in the 1930s for example) and even taking over major Broadway houses as a launch platform for new releases. Come the end of the 1960s , Britain had lost its production grip on the world stage. Though movies were still being made in Britain they were often funded by Hollywood, or were B-movies or genre-specific such as Hammer horror.

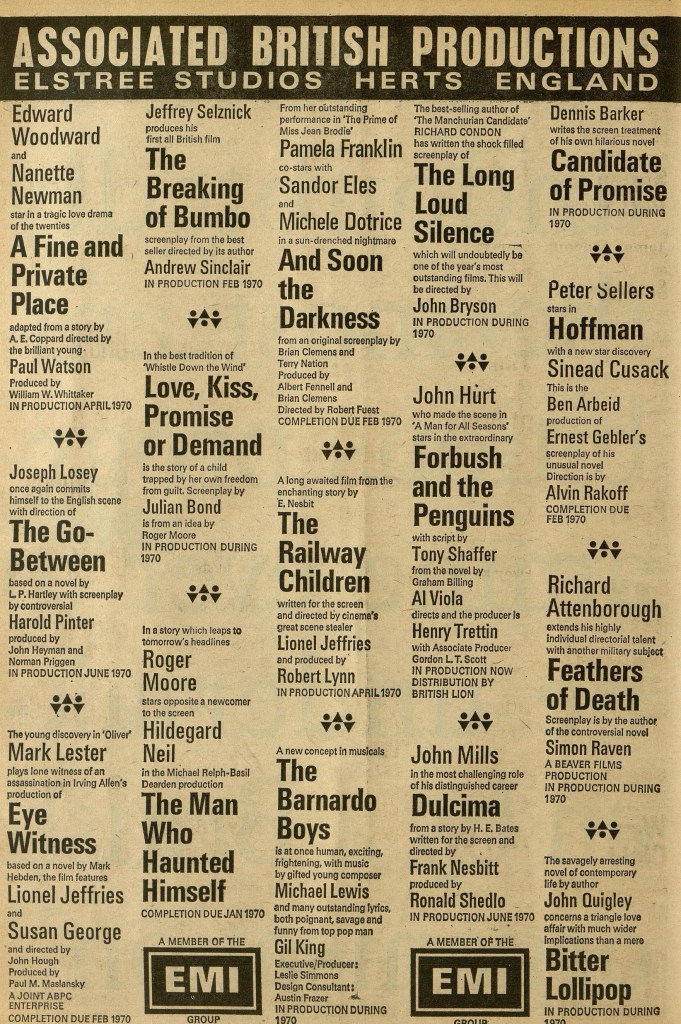

In 1969, Associated British Picture Corporation, following a takeover by EMI, relaunched as a major production entity, aiming to provide increased programming for its own 270-strong ABC cinema chain as well as hitting the export market. Bernard Delfont, chairman of ABPC, set up two production strategies that he intended to run in parallel. He brought in director Bryan Forbes (King Rat, 1965) as production chief of ABPC while Nat Cohen, head of ABPC subsidiary Anglo-Amalgamated, would augment that effort.

Of the 26 features planned, only 15 were made.

Forbes took on the role after initially signing a three-picture deal with Delfont which developed into “something wider…at a time of real crisis.” Forbes explained his motivation: “I think if you’ve been a critic as I have over the years…you’ve got to put up or shut up. And if the job is offered to you, you can’t turn it down and then go on criticising.”

The initial slate was being made with no guarantee of foreign distribution. Even getting a foothold in Britain was difficult. “We are very dependent…on getting West End outlets. There’s a long queue and we don’t have any particular pull.”

(In Britain at this point, roadshow – which to a large extent was no longer the favoured release device for big budget pictures in the U.S. – still dominated the West End and the type of picture being envisaged was more targeted towards the circuit. But a West End run was always seen as a mark of quality. The downside of the West End release was that it delayed movies reaching the provinces and by the time they did all the initial media interest was long forgotten.)

Budgets were being assessed to meet the prospect that a very successful film could recover its negative costs on a British release alone, with anything else pure profit. Trying to appeal to the international and/or U.S. market at the outset was too complicated and expensive a proposition. And there was always the prospect that with the production well running dry in American, that a distributor, with a hole to fill, would come calling.

ABPC allocated a total budget of £36 million to make 28 pictures, with Forbes’ outfit taking the lion share, leaving Nat Cohen only $7 million to make 13 movies. According to Delfont, it was the “most ambitious” program ever scheduled by a British company. While certainly an overstatement given the investment by Rank, ABPC and Gaumont-British in the past, it nonetheless captured media attention.

The Forbes project didn’t go according to plan. Hoffman (1970) with Peter Sellers, thriller And Soon the Darkness (1970), The Man Who Haunted Himself (1970) starring Roger Moore, The Breaking of Bumbo (1970) and Mr Forbrush and the Penguins (1971) headlining John Hurt and Hayley Mills all flopped, despite costing a lot less than originally expected. The Railway Children (1971) was the only undeniable hit while The Tales of Beatrix Potter (1971) made a profit. Raging Moon / Long Ago, Tomorrow (1971), with Forbes directing Malcolm McDowell and Nanette Newman, and Dulcima (1971) with John Mills and Carol White also ended up in the red.

Forbes fared much better heading up MGM-EMI, a co-production unit set up in 1970, which produced hits The Go-Between (1971) and Get Carter (1971). Forbes resigned in 1971.

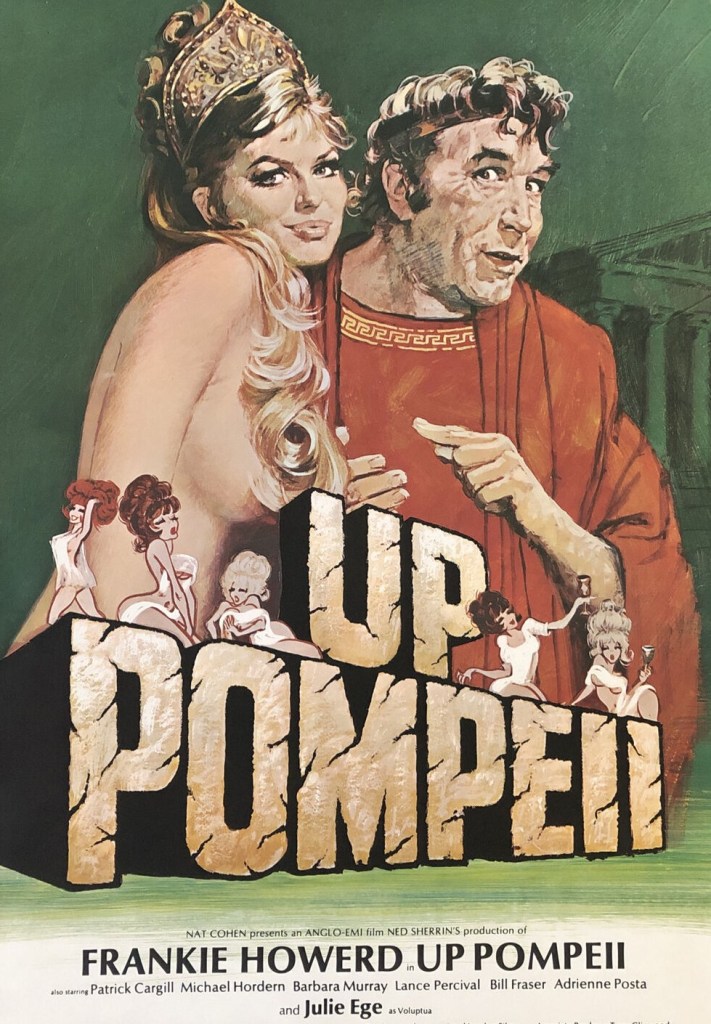

Nat Cohen, while pandering to a lower common denominator, enjoyed more straightforward success with sex-change comedy Percy (1971), and big screen versions of On the Buses (1971), Up Pompeii (1971) and Steptoe and Son (1972) – and their various sequels – Richard Burton as Villain (1971), Fear Is the Key (1972), and Stardust (1974) while Murder on the Orient Express (1974) with an all-star cast was a huge global hit.

In 1976 Michael Deeley and Barry Spikings became joint managing directors of EMI and aiming for an international audience fronted part of the finance for The Deer Hunter (1978), Sam Peckinpah’s Convoy (1978) and Walter Hill’s The Driver (1978) and had significant investment in Columbia pictures like Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and The Deep (1977).

But the British invasion amounted to very little in the end, as Hollywood, led by gargantuan hits of The Godfather (1972), Jaws (1975) and Star Wars (1977) swept all before them and made it impossible for British-made films to compete either on a commercial or artistic basis.

The experiment was a massive flop. EMI failed to break into the American market and, in fact, the box office achieved was on the dismal side. Best performers were Get Carter and The Go-Between both estimated to achieve rentals of just under $2 million. Tales of Beatrix Potter didn’t reach $1 million and Villain not $750,000. The Railway Children couldn’t manage $500,000 nor Percy $250,000 and none of the others even crossed the $100,000 mark. It was considered such a footnote in British movie history that it didn’t merit a mention in Sarah Street’s Transatlantic Crossing, British Feature Films in the USA (Continuum, 2002).

SOURCES: Alexander Walker, Hollywood England, (Orion paperback, 2005) p426-440; Advert, Variety, January 21, 1970, p12-13; Derek Todd, “The Emperor of Elstree’s First 300 Days,” Kine Weekly, March 7, 1970, p6-8, 19; “MGM-EMI In Joint Deal On British Filmmaking,” Box Office, April 27, 1970, p7; “MGM Setting EMI CoProds,” Variety, June 10, 1970, p3; “MGM-EMI To Produce 12 Films Annually,” Box Office, July 6, 1970, p6; “From $10-Mil and Up, Rentals, to $100,000 and Less,” Variety, November 12, 1972, p5.