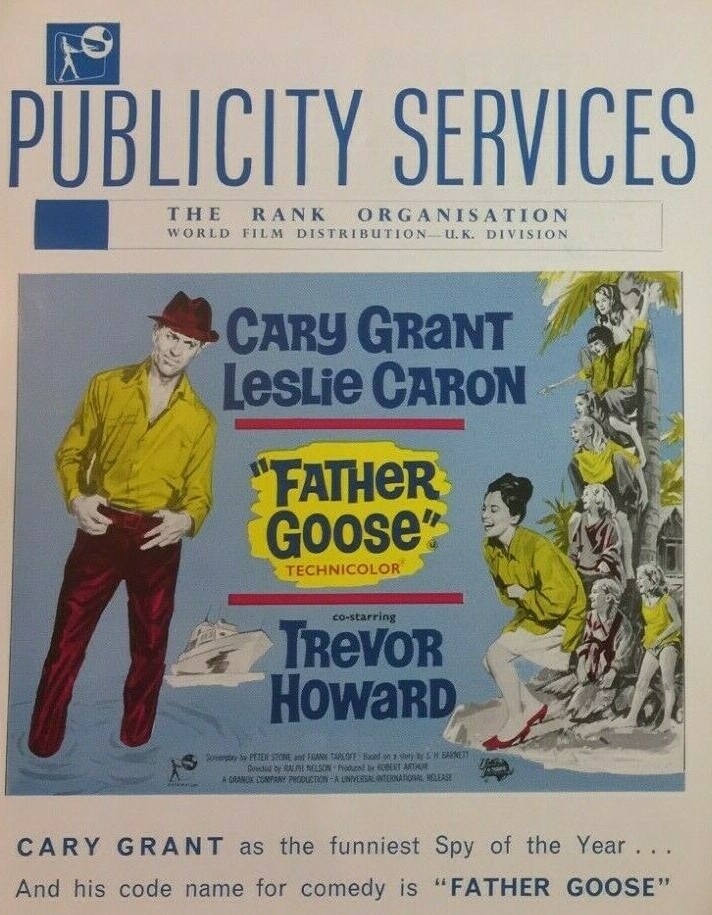

The African Queen with kids or 100 ways to see Cary Grant deflated. The penultimate movie in the screen giant’s career is a tame affair especially after the thrilling Charade (1963) and it may have prompted him to shy away from attempting to carry on a romance with a woman decades younger as occurs in his final offering Walk, Don’t Run (1966). When Trevor Howard (Von Ryan’s Express, 1965) effortlessly steals the picture with a performance that turns his screen persona on its head, you can be sure it’s not quite top notch.

In World War Two, Walter (Cary Grant), a hobo on water with a knack of stealing official supplies, is commandeered by British officer Houghton to operate a radio outpost on a Pacific island giving early warning on Japanese aircraft sorties. While there, he encounters Catherine (Leslie Caron), a French schoolmistress and consul’s daughter, in charge of a pack of female schoolkids.

Effectively, both relationships follow a pattern of verbal duels, initially with Walter losing them all as he is kept on a leash by Houghton and then is beaten by teacher and children. The kids steal his hut, his bedding, clothes (shredded and sewn to fit young girls), food, booze and sanity.

The straight-laced Catherine is happiest when straightening a picture. Walter only regains some of his standing when it transpires he has practical skills like catching fish, repairing a boat and encouraging to talk a girl who has been traumatized by war into temporary dumbness. Naturally enough, any time Leslie warms to him he does something off-putting. But gradually, of course, they get to know each other better, romance is in the air, and secrets are revealed, his hidden past laughable.

It’s a series of set pieces, designed to make the most of Cary Grant’s deftness with physical comedy, he can pull faces with best of them and long ago mastered the double take and the pratfall. So there’s little here you’ve not seen before. And the trope of man and woman trapped on a desert island – most recently probably best exemplified given its inherent twist in Heaven Knows, Mr Allison (1957) – has long been over-used and this addition to the sub-genre suffers from lack of originality.

The little blighters are less an innovation than a complication (or perhaps a multiplication) but they do have the advantage of reducing him to impotence, since he can hardly deal with their transgressions the way he might Catherine. And of them is smart enough to realize that he runs on booze and rations this out.

All in all it’s gentle stuff, nothing too demanding, redemption neither an issue nor an option. Cary Grant is an unusual species of top star in that, as with Rock Hudson and a few others, he didn’t mind being the butt of all the jokes, and in some respects sent up his screen persona.

Keeping Cary Grant in check might well be a sub-genre of its own, so Leslie Caron (Guns of Darkness, 1962) is inevitably limited in the role, primarily a foil/feed for the Grant, the part not not quite of the caliber of the roles played by actresses in his thrillers such as like Grace Kelly (To Catch a Thief, 1965), Eva Marie Saint (North by Northwest, 1959) and Audrey Hepburn in Charade.

As I mentioned, Trevor Howard is the surprise turn, and steals the show. Ralph Nelson (Soldier Blue, 1970) directs from s script by Peter Stone (Charade), Frank Tarloff (The Double Man, 1967) and S.H Barnett, a television writer in his only movie. I’ve clearly under-rated the script because it collected the Oscar.

Perfectly harmless and enjoyable, if a tad obvious.