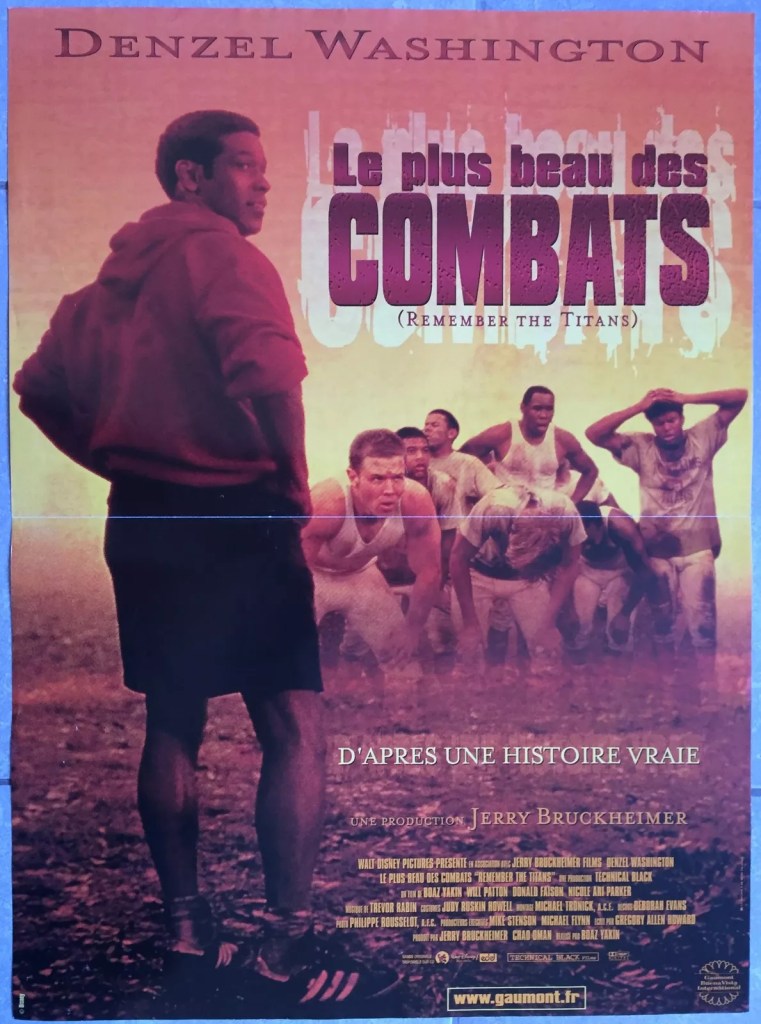

Denzel Washington’s breakout movie. An odd statement given he had already appeared in such box office hits as The Pelican Brief (1993), Philadelphia (1993), and Crimson Tide (1995). But in the first two he was second banana to, respectively, Tom Hanks and Julia Roberts. And only the first topped the magical $100 million mark – though only just – the other two reaping $77 million and $91 million, respectively. But all three had considerable juice – Julia Roberts well into her stride as a box office phenomenon, the AIDs drama courting Oscars, uber-director Tony Scott helming the nuke sub drama – and backed with big marketing dollars

Apart from Washington, Remember the Titans had nothing going for it. Nobody else with any box office marquee. And covering a sport that had little traction in the U.S. and zilch in the global market. North Dallas Forty (1979) with Nick Nolte had hauled in just $26 million, The Program (1993) pairing James Caan and Halle Berry just $23 million, biopic Rudy (1994) $22 million and even the heavyweight Any Given Sunday (1999) helmed by Oscar-winning Oliver Stone and featuring Oscar-winning Al Pacino and a roster of top names could only climb to $75 million.

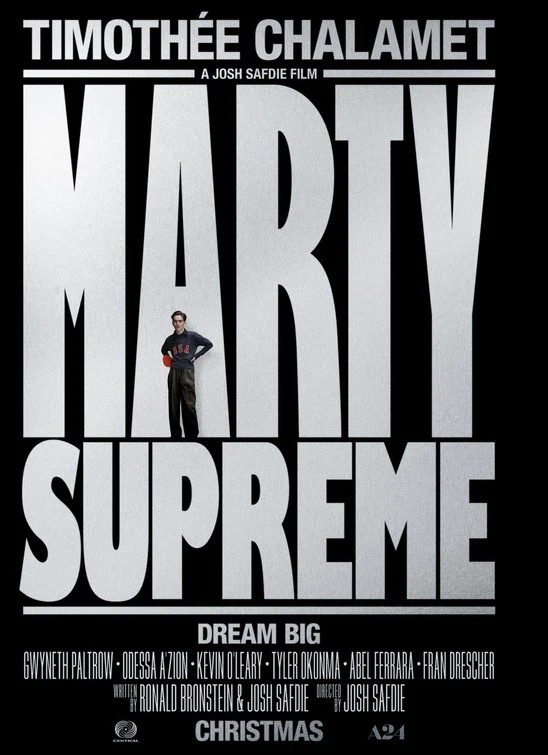

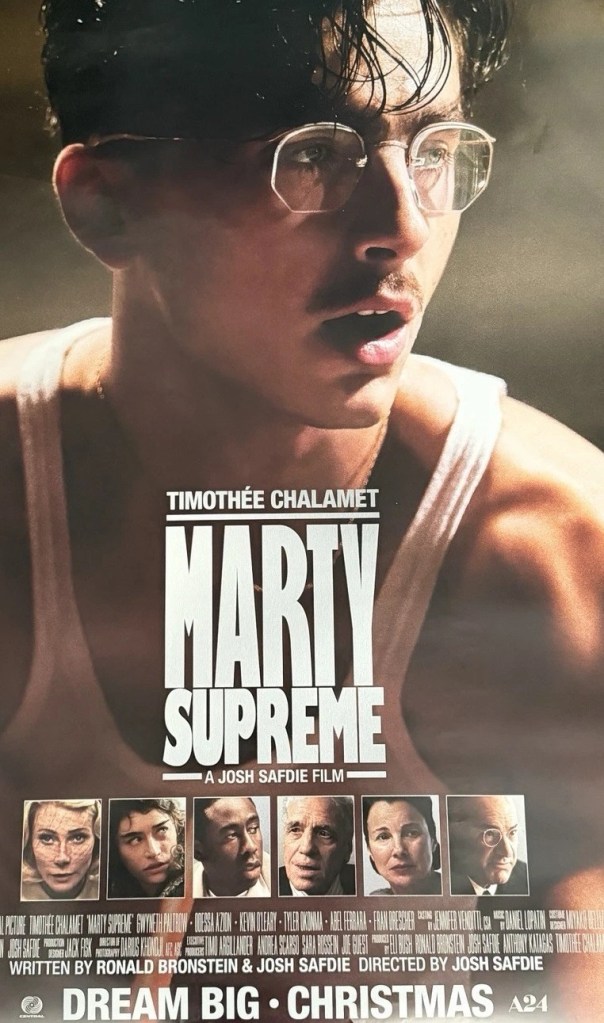

Remember the Titans hit $115 million, the biggest movie of Washington’s career, the biggest sports movie of all time. And here’s the kicker. None of the characters were instantly likeable. You had a ruthless hardass coach who refuses to listen to advice, the jocks are all spoiled and entitled, even the kids are likely to turn you off. But where recent pictures like Roofman (2025), Marty Supreme (2025) and After the Hunt (2025) leave you with no liking for the characters at the end, here the opposite is true.

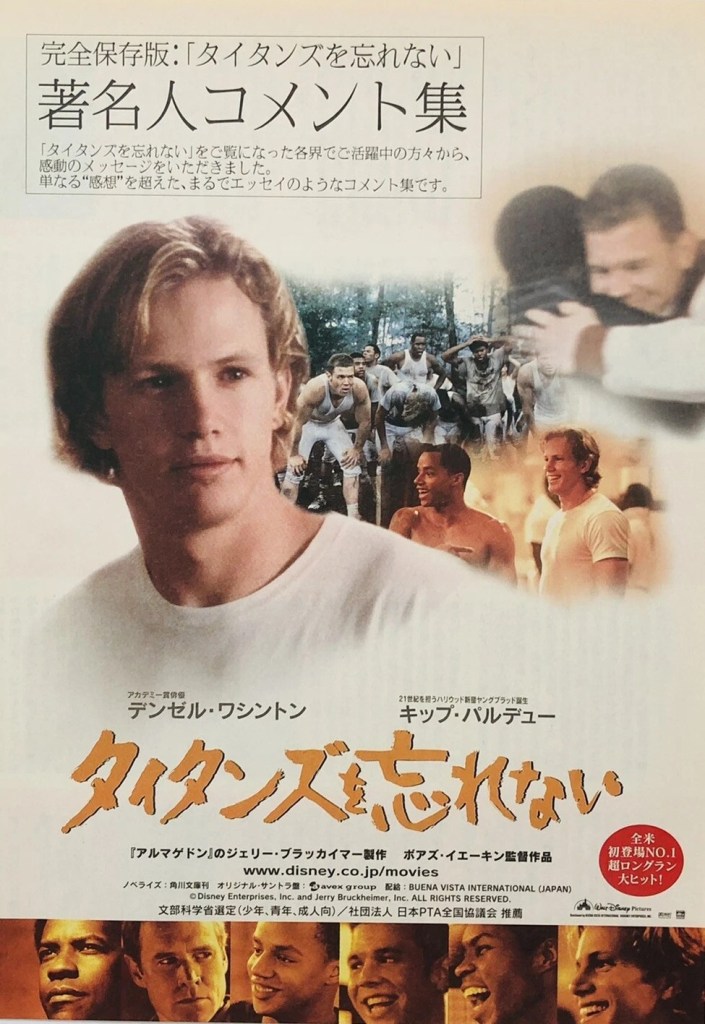

Each character has a rival. Incoming college coach Herman Boone (Denzel Washington) has little time for the man he replaced, Bill Yoast (Will Patton). Incoming Sunshine Bass (Kip Pardue) nettles team captain Gerry Bertier (Ryan Hurst) who in turn clashes with newcomer Julius Campbell (Wood Harris). Even Yoast’s daughter refuses to play nice with Boone’s daughter.

All this plays out against a background of racism. In 1971 T.C. Williams High School in Alexandria, Virginia, has been integrated, a notion largely opposed by the existing white authorities and residents, including Bertier’s mother and girlfriend (Emma) Kate Bosworth who refuses to shake a black hand. Like his daughter, Boone isn’t about to play nice and he proves to be the worst kind of driven coach, pushing his players to more demanding physical levels and punishing them when they don’t grasp his plays.

But he does understand how a team works, that it won’t function as a collection of individuals, no matter how brilliant – and the better the players like Bertier, the only All-American on the field, expect to be treated differently. Bonding, in this instance, forces black and white players to learn about each other’s lives.

And you could say the same about victory. Nothing brings a team together like winning. A successful team crosses all racial boundaries.

So we get the usual last-minute touchdowns, the individuals finding redemption on the field, the cheating and off-field maneuvers, and the “coming together” that was such a big part of Al Pacino’s team in Any Given Sunday.

Music plays a big part, as white players begin to enjoy what they initially view as black music, and as the team take music as their very own bonding exercise, dreaming up a theme song and entering the field of play with an original song-and-dance number.

Denzel Washington is the driving force and the fact that he’s not a do-gooder and is just trying do his job rather than undertaking any wider virtue-signalling remit is what propels the picture. Will Patton (Entrapment, 1999) is solid. Wood Harris (The Wire, 2002-2008) and Donald Faison (Scrubs, 2001-2010) catch the eye. Kip Pardue (Driven, 2001) was the breakout youngster and current box office behemoth Ryan Gosling has a small part.

Under the direction of Boaz Yakin (Safe, 2012), it fairly rolls along as the rivalries develop or are resolved. Written by Gregory Allan Howard (Ali, 2001).

Not a critical hit at the time and still pretty much written off by the media, but picked up a strong head of steam among audiences at the time and since.

Thoroughly enjoyable.