So pitch perfect I’m almost tempted to put it up a notch to five stars. It’s hard to find anything that would detract from what was an extremely enjoyable entertainment. They don’t make feelgood movies anymore, certainly not of the innocent Home Alone (1990) variety, because once again we’re back to the William Goldman dictat of “nobody knows anything” meaning nobody knows how movies will perform. Everything these days that might fall into the feelgood category has to have such an edge it removes it from the equation.

Which is not to say this doesn’t feature the hard stuff. It does – and how. But for once it’s about the little people without some director with ideas above their station trying to make a political or artistic point. In my time, I’ve known four part-time musicians. They were the opposite of my expectations. Not because they weren’t drugged-out or drunk, but because they didn’t conform to my idea of musicians hellbent on being creative, writing their own music, failing to get record deals. Nope, these were guys only too happy to play anyone else’s stuff if it meant they could get up on stage and perform, even if that was – most commonly – at a wedding.

So that’s where we are here. I’m not sure if tribute singers and bands are a cut above the musicians who play at weddings if only because they have to perfect their imitations and spend more on costumes.

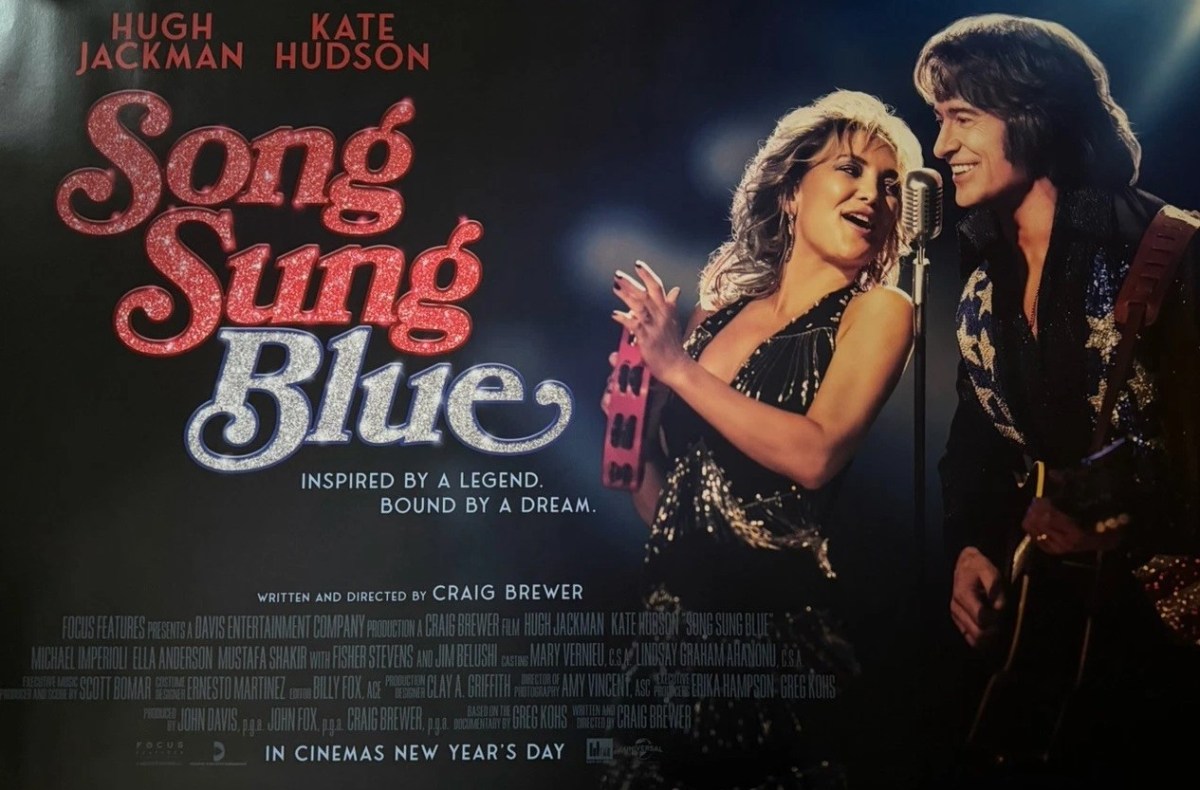

Car mechanic Mike (Hugh Jackman) has all the makings – the moves, the poses – of a rock star frontman except he’s reduced to performing for a touring tribute outfit run by Mark (Michael Imperioli). He’s got some of the musician’s baggage, a recovering alcoholic and divorced. But he’s still struggling to conform until he meets bubbly hairdresser Claire (Kate Hudson), single mom and glitzy tribute singer. Music, or more precisely their dreams, have, nonetheless, taken a toll on both previous marriages with their offspring driven to truculence.

In the course of romancing her quick-style, Mike convinces Claire to join him to join the backing band of his “Neil Diamond Experience,” with somewhat grand aspirations to “interpret” the famed singer’s music and like a rock star determined to play his faves rather than fan faves, planning to open his set with the more obscure “Soolaimon” rather than the widely popular “Sweet Caroline.”

And while this doesn’t head straight for the trashy side of the business like The Last Showgirl (2024) it’s still in the ballpark of the small-time. Mike’s manager is his dentist (Fisher Stevens), their bookings kingpin runs a dismal bus tour operation, and their first gigs are on the humiliating scale.

Even so, once the music kicks in so does the feelgood factor. And I was just humming along to the numbers, enjoying the tale of the little guy getting his big break (opening a concert for Pearl Jam) when I’m knocked for six by a catastrophe that nobody saw coming.

And the rest of the movie is coping with that disaster. Which should have shifted it into another genre entirely and dipped into the mawkish. But it doesn’t. Director Craig Brewer’s (Black Snake Moan, 2006) grip of the material is so tight he keeps it all very earthbound, giving both Claire and Mike equal time when we hit the recovery home straight. And while we’re rooting for Claire through her ordeal there’s a ticking clock where Mike is concerned. He has serious heart problems.

We only realize just how bad his condition is when Mike starts showing Claire’s daughter Rachel (Ella Anderson) how to use a defibrillator just before he falls unconscious. Brewer’s concise use of his material is brilliant. We only learn that Mike was a Vietnam vet when he uses Army planning skills to teach Rachel how to plan for pregnancy.

And I can’t be only fed up to be presented with characters always tinkering with engines without demonstrating that they know a spanner from a wrench. Here, Mike explains to Claire that she’s mend the hole in her oil tank simply by pouring in oil because it contains some kind of mending material. I didn’t know that, I doubt if many in the audience did, but it was a superb way of demonstrating his mechanical knowledge.

There are two other brilliant scenes that epitomize the director’s skill. One, believe it or not, focuses on door-knocking. The other concerns a fire that isn’t a fire – but much worse. But Brewer’s main achievement is weighting this correctly. He doesn’t, as would have been the temptation, hand this on a platter to Claire since she will carry the more obvious emotional heft. Instead, screen-time-wise, it’s pretty much evens.

And although Kate Hudson (Glass Onion, 2022) is attracting all the critical attention, that’s unfair on Hugh Jackam (Deadpool and Wolverine, 2024) who not only holds the stage act together but the family.

One of the other pleasures here is seeing a bunch of supporting actors just being ordinary people, not the slimeballs or weirdos who often go with the territory. I’m talking about Michael Imperioli (The Sopranos, 1999-2007), Jim Belushi (Fight Another Day, 2024) and Fisher Stevens (Coup! 2023). Written by Brewer based on the documentary Song Sung Blue (2008) by Greg Kohs.

A great start to the year.