Lollapalooza! Trash horror is back. Step aside the relatively classy Blumhouse offerings and the torture porn of the Saw dynasty, what the world needs now is a throwback to the so-bad-it’s-good style of horror where blood flows like a burst dam and reanimated corpses trail yards of intestines.

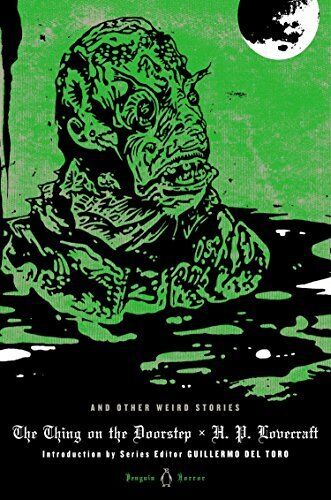

Not forgetting that the star turns are either pop-eyed or garnish every line with a smirk. H.P. Lovecraft may well be turning in his grave, or relishing every camped-up ramped-up moment of this updating of his tale of gender-bouncing possession The Thing on the Doorstep. Throw in hypnosis, bdsm, smoking treated as illicit pleasure, and the kind of sexuality that used to be the prerequisite of the DTV scene.

Dr Derby (Heather Graham) has to be the dumbest psychiatrist ever to hit the screen, breaking the golden rule of never seeing a client, especially one as deranged as Asa (Judah Lewis), in their house. But, sensing a book or at least a write-up in a journal, she discovers he’s possessed by nasty father Ephraim (Bruce Davison). Or by a creature going back centuries whose main aim in life/death is to jump like an eternal parasite from person to person, indifferent to gender.

Such transference works magic with the sex genes, the good doctor soon capable of playing the kind of sex games her husband never imagined while the snarky Asa is turned into a sex god with magnetic appeal to women. So, when everyone isn’t at it like rabbits, they get a tad worried about seizures.

In a nod to Dracula, it’s brains not hearts that have to be put out of commission, and there’s a whole bunch of demonic mumbo-jumbo served up to make this sound believable but by this point the audience is beyond caring. More, we call out, give us more – gore, sex, transgendering gone mad, references to Dunwich, bitchfights, corpses that won’t die – who the hell cares.

Mostly, it’s the kind of slam-bam horror fest that dominated the 80s/90s, with prime specimens of either sex to the fore. There’s a desultory pair of cops who do little more than add narrative confusion: who died, or did they even die, and was it all in Dr Derby’s mind? And once the sly Dr Upton (Barbara Crampton), also a dumb psychiatrist, who is either Derby’s sister or best pal, with a shady past, enters the picture the possibilities multiply.

Whoever is in charge of pushing a movie into cult territory better have a look at this especially when you consider the ropey camerawork – shaky or spinning screens dominate – not to mention that idea that was once the preserve of cartoons where the screen disappears into a dot. Cinematically, if anyone is remotely interested in that, there’s one scene of note, where the usual stunt of following action in a rearview mirror becomes seeing it from a vehicle’s reversing screen.

At times Heather Graham looks as if she’s walked in from playing the pop-eyed innocent of Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me (1999), other times she’s time traveling back to the uninhibited Killing Me Softly (2002). Whatever, she has worked out subtlety is not required. Judah Lewis pays homage to Bruce Willis and Mickey Rourke by reviving their trademark smirk. Johnathan Schaech (That Thing You Do, 1996) spends most of his time shirtless, showing off his pecs and hairy chest, and trying to get obsessive wife to drop her workload and jump into the sack. Craching additiont to the Bruce Davison (Last Summer, 1969) can, and Barbara Crampton (Alone with You, 2021) has a sackload of this kind of thing (left on a doorstep or not) in her closet.

Dennis Paoli (Re-Animator, 1985) did the updating, Joe Lynch (Point Blank, 2019) the camping up to high heaven.

Judging from size of the cinema audience when I saw it, this isn’t going to last more than a week at your local multiplex. So drop your planned schedule and get there now.

Otherwise Shudder has this for streaming in January.

Call the cult police!