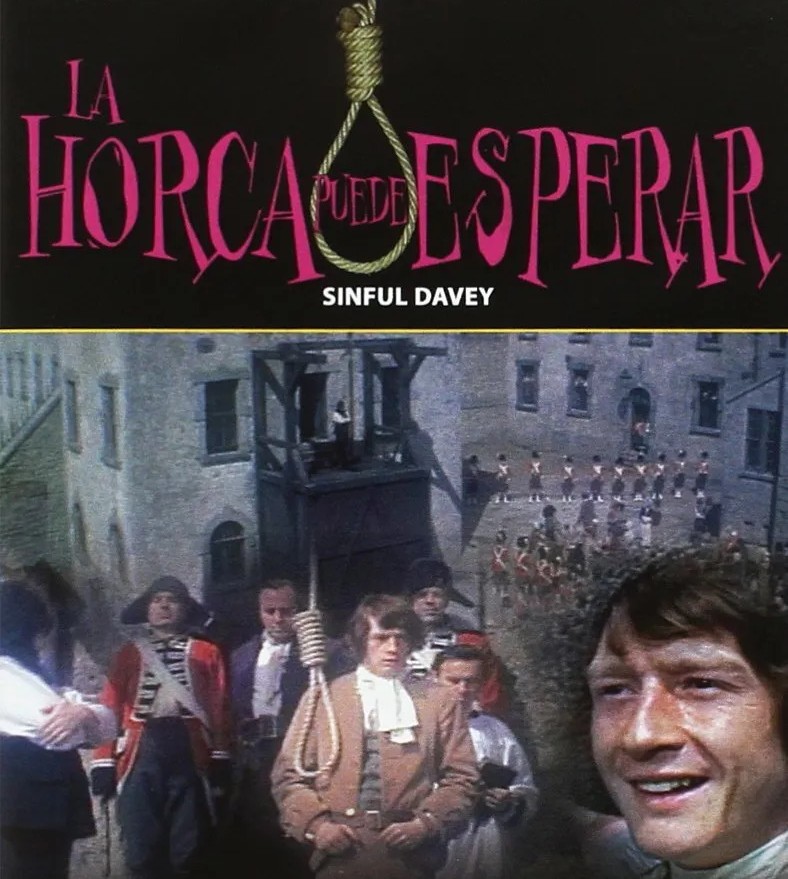

Major disappointment from a director of the caliber of John Huston. Granted, the quality of his output during the decade had been variable but this marked a new low and the suspicion lingers that he only took on the gig to spend time in Ireland – the movie was filmed there – where he had set up a home in the grand manner of a country squire. Equally odd is James Webb as screenwriter. Having chronicled the American West via How the West Was Won (1962) and Cheyenne Autumn (1964), Webb had turned his attention to British history, beginning with Alfred the Great (1968).

But where that had at least historical reality to guide the narrative, here Webb relies on the dubious autobiography of the titular subject, resulting in an episodic, picaresque, sub-Tom Jones (1963) and even sub-Where’s Jack? (1969) tale set in the Scottish Highlands. And much as John Hurt later achieved considerable recognition for his acting, the role, as played, could have been handled just as easily by any number of rising male stars, since, beyond being able to affect two accents – broad Scots and upper-class English – little is required.

In fact, the director clearly couldn’t distinguish between the Irish and the Scottish accent as among the joblot of accents, none more than serviceable, there is many an Irish lilt. As if to make the point that he couldn’t care less, you will also discern on the soundtrack a refrain from “Danny Boy.”

Beyond that it made a good scene, quite why Davey Haggart (John Hurt) decided to announce his desertion from the British Army in such ostentatious manner is difficult to understand. He’s a drummer, marching along, banging said drum, when he takes it into his head to jump off the nearest bridge into the nearest river, complete with drum, only to find himself headed for a mill. In possibly the best line in the script, seeing the mill wheel blocking his escape, he mutters, “Who put that there?”

From here on it’s a tale of pursuit – two actually. Lawman Richardson (Nigel Davenport) leads the merry chase but he’s also got childhood sweetheart Annie (Pamela Franklin) on his tail to ease him out of scrapes in the hope that he’ll reform. Beginning as a pickpocket, he switches to highway robbery and piracy, rarely with particular success. Loaded down with booty on the carriage he has stolen, for example, he loses control of the horses and is left at the side of the road, as poor as when he started.

He’s certainly inventive but contemporary audiences will recoil from the notion of using the head a height-challenged man aloft another’s shoulders to test the rotting rafters inside a jail, leading not to escape but to a home-made pleasure parlor, since it provides entry to the female jail above where our hero establishes himself as a pimp.

But that’s as inventive as this picture gets and in the manner of Cat Ballou and Where’s Jack? you know that whenever a hero heads towards the gallows you can be sure the hanging will be thwarted. The period setting – the 1820s – offers little assistance, as the picture could be set any time before the invention of steam, and could as easily have taken place in a galaxy far far away long long ago called Brigadoon for all the period authenticity shown.

This didn’t lead to instant stardom for John Hurt and possibly just as well as he’d have been wasted in a series of ingenue roles. Pamela Franklin (And Soon the Darkness, 1970) doesn’t have much to do beyond trying to master a Scottish accent. Nigel Davenport (Play Dirty, 1968) was in his element playing yet another frosty authoritarian figure.

John Huston (Night of the Iguana, 1964) did prove one thing – that he lacked the knack for comedy.