One of those bonkers pictures whose nuttiness is initially irritating but ends up being thoroughly enjoyable once you give in to the barmy plot and overheated melodrama. Murder, suicide, madness, illicit sex, blackmail – and that’s just the start of this farrago of nonsense. And set in Liverpool before The Beatles made it famous.

Christine (Susan Hayward), a doctor, is jailed when she kills her married seriously ill lover in a mercy killing. She’s not convicted of the murder but of the lesser crime of medical malpractice, but after serving an 18-month sentence finds she is unemployable, even in more lowly professions where her prison stretch counts against her.

When she is hired by the attorney Stephen (Peter Finch) who prosecuted her to look after his mentally ill wife Liane (Diane Cilento), the audience will already smell a rat given that Christine has changed her name and therefore the lawyer must have made considerable effort to track her down. His argument is that since she is no longer a qualified practitioner, she cannot advocate to have his wife committed to a mental institute, as a proper doctor would be required to, since Liane is clearly a danger to herself and other people. Your immediate suspicion is that Christine has been hired to take the rap once Liane is bumped off.

And it doesn’t take long for Christine to work out that not everything adds up. Liane is given enough rope to hang herself, access to a car to cause an accident, access to a horse which could easily bolt or fall.

Liane has been told her Irish father died in an accident where she was driving, the incident that triggered her madness. But when we discover the father, Captain Ferris (Cyril Cusack), is very much alive that’s the cue for a slew of unlikely events. When Liane finds her father, he’s not in the least a candidate for canonization, but an alcoholic. That triggers further mental trauma. And another accident, self-inflicted. After Christine administers pills, the young woman is found dead.

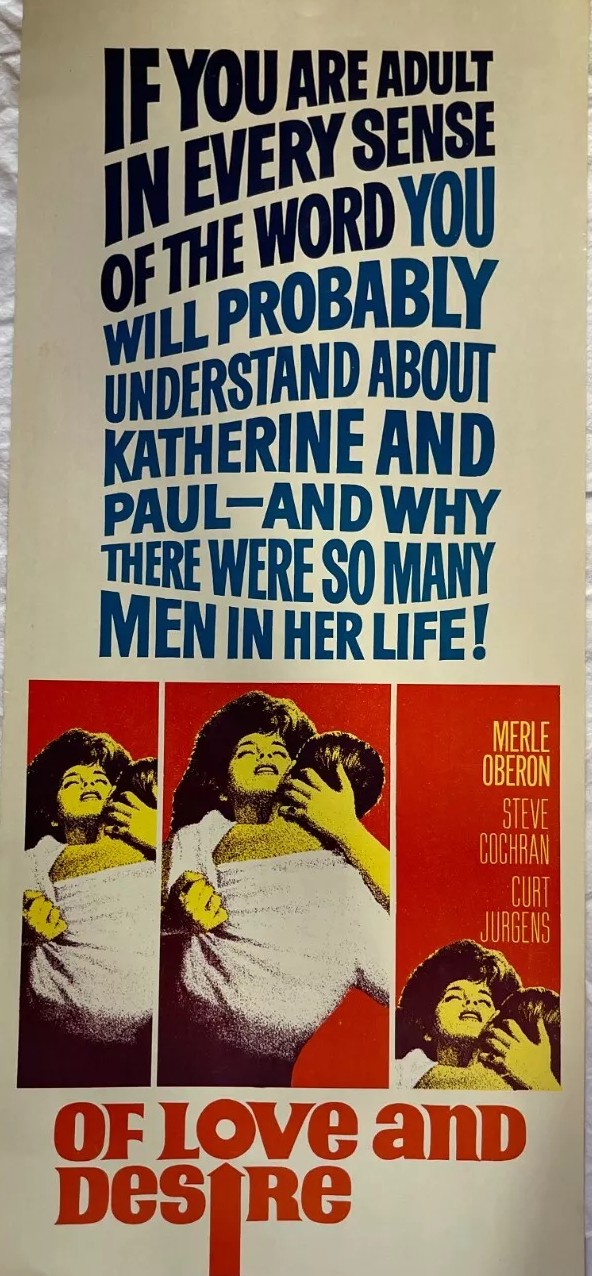

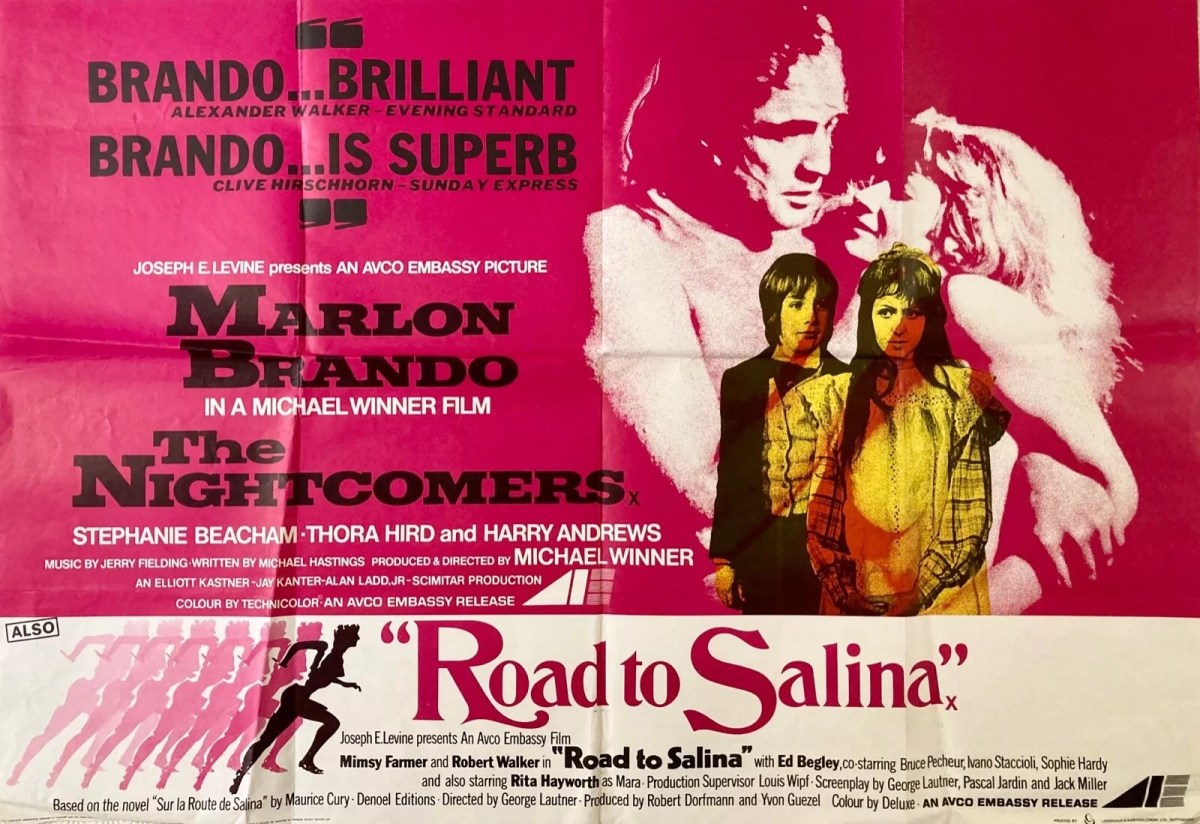

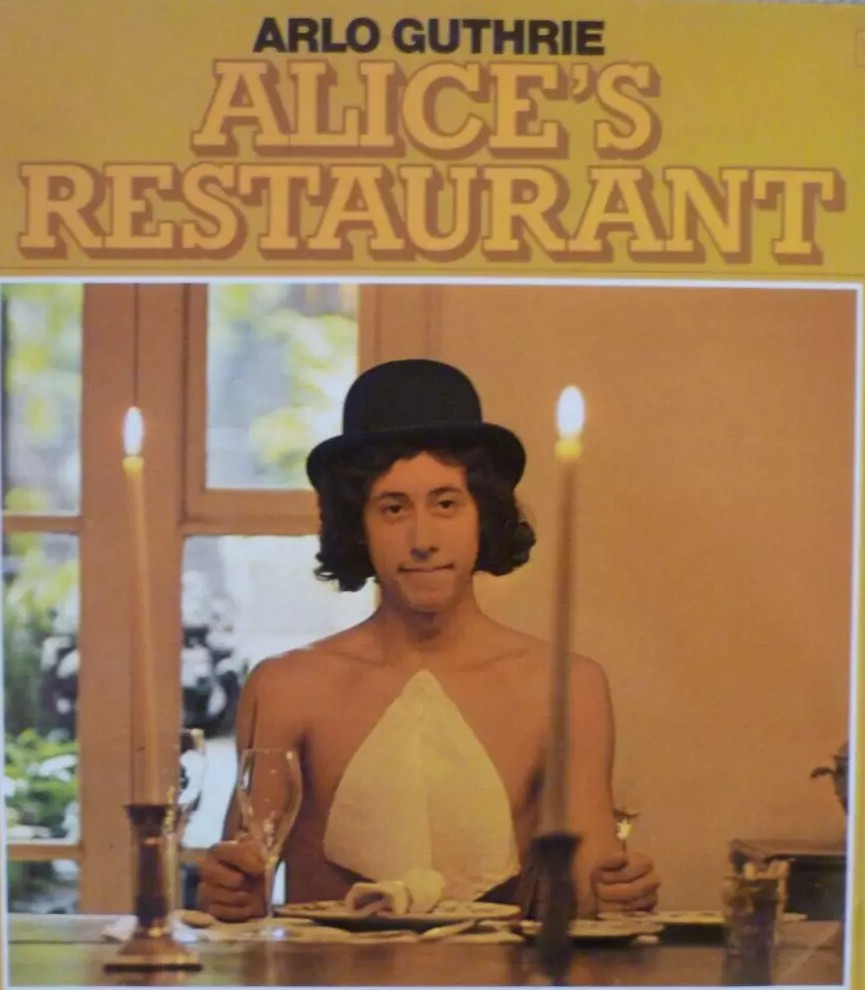

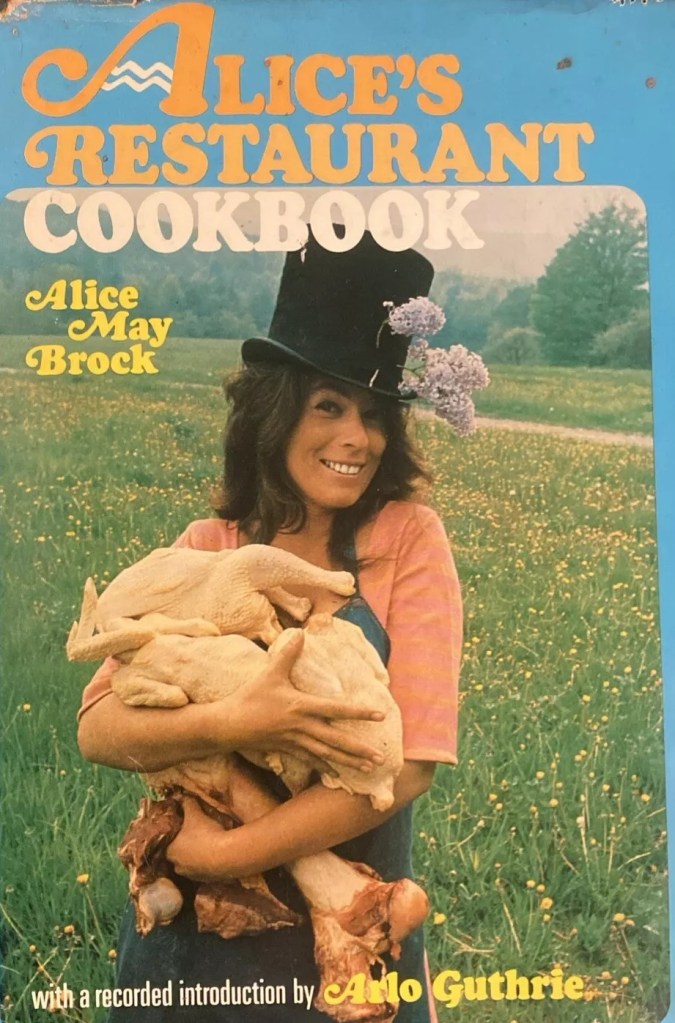

mentioned in this poster.

Naturally, an inquest brings up Christine’s past and suspicion falls on her. And that would be par for the course, and it would be up to the condemned woman to find a way to prove her innocence. But that takes us into even murkier depths.

There’s bad blood between Capt Ferris and Stephen and the inference that this was only resolved by the father offering his underage daughter to the lawyer to be followed by the unscrupulous father blackmailing Stephen. Then it turns out there’s no case to answer and that Christine is innocent because, blow me down, Liane committed suicide.

But what should have been a straightforward, if unlikely, murder plot comes unstuck because it can’t make up its mind what it wants to be. Too many ingredients are thrown into the pot and the result is a mess.

Even the queen of melodrama Susan Hayward (Stolen Hours, 1963) can’t rescue this. And the pairing with Peter Finch (Accident, 1966) doesn’t produce the necessary sparks. Despite a variable Irish accent, Diane Cilento (Hombre, 1967) comes off best as the wayward deluded young woman.

Robert Stevens (In the Cool of the Day, 1963) directs from a screenplay by Oscar-nominated Karl Tunberg (The 7th Dawn, 1964) adapting the bestseller by Audrey Erskine-Lindop.

Had every opportunity to be a star attraction in the So Bad It’s Good sub-genre but fails miserably. Still, if you enter into the swing of things, remarkably tolerable.