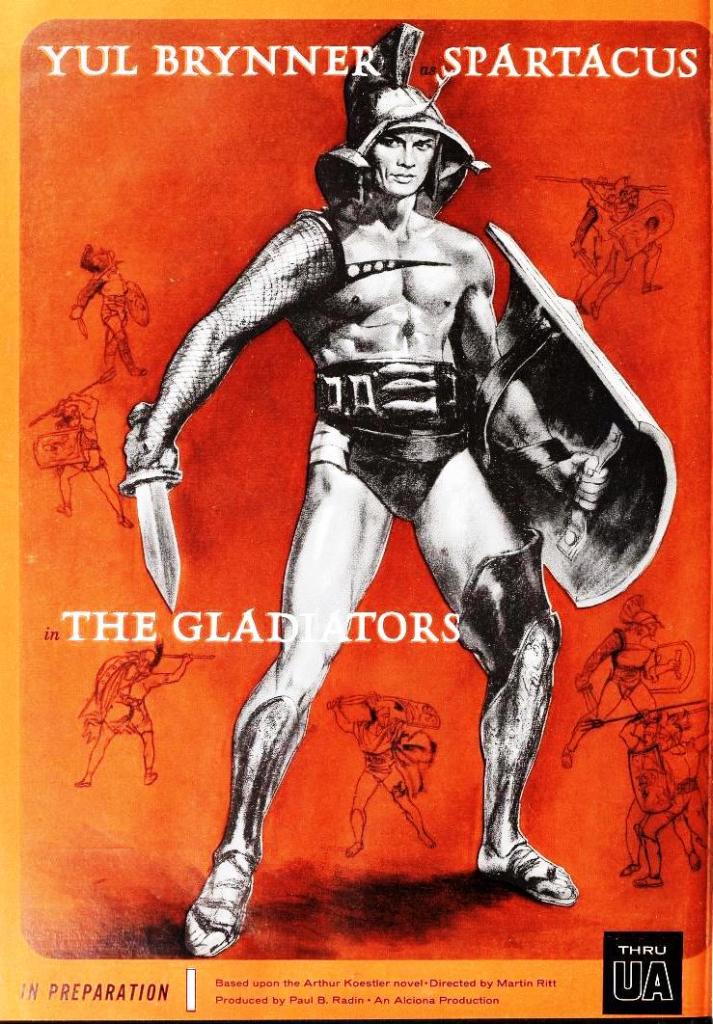

When I wrote my book some years back on the making of The Magnificent Seven (1960) I was aware that Yul Brynner had attempted to set up a project called The Gladiators in direct opposition to rival Kirk Douglas venture Spartacus. What I didn’t know until I came across this fascinating new book, telling the untold story of The Gladiators vs. Spartacus, Dueling Productions in Blacklist Hollywood by Henry MacAdam and Duncan Cooper, was just how close Brynner came to derailing the Douglas production. Indeed, at first it appeared Brynner’s The Gladiators, based on the novel by Arthur Koestler (Darkness at Noon, The Ghost in the Machine), was a cinch to be first past the post. After winning the Best Actor Oscar for The King and I (1956) and starring in box office behemoth The Ten Commandments (1956), Brynner was set to become a movie mogul after being handed a record $25 million – $230 million at today’s prices – from United Artists for 11 pictures. His first project was The Gladiators on a $5.5 million budget, Meanwhile, Douglas, rejected for the title role in the forthcoming Ben-Hur, his picture Paths of Glory (1957) producing dismal returns, struggled to find funding for Spartacus, based on the book by Howard Fast.

There are instances of two studios embarking on similar projects at the same time – sci fi adventures Deep Impact and Armageddon appeared within months of each in 1998 but Warner Bros and Twentieth Century Fox decided to combine competing movies about a skyscraper on fire into The Towering Inferno (1974). Here, as much as efforts were made to combine the projects both actors were determined to continue the battle despite the potential competition. At another point, Brynner sought to recruit Douglas for The Magnificent Seven. The race to the screen went back and forth for a couple of years, Brynner unable to choose between the historical drama and the western, while Douglas had the luck to have as his agent Lew Wassermann, in the process of buying up Universal who determined that Spartacus would be the ideal prestige vehicle to relaunch the studio.

What gives this volume special significance is that the films were being produced against the backdrop of the blacklist, the anti-Communist hysteria stirred by HUAC in the late 1940s/early 1950s. Screenplays for both films were the work of blacklisted writers, Abraham Polonsky on the Brynner side and Dalton Trumbo for Douglas. Polonsky was writer-director of Force of Evil (1948) as well as writer of another quintessential film noir Body and Soul (1947), for which he was Oscar-nominated, before his career was prematurely interrupted. Trumbo was held in even greater esteem, Oscar-nominated for Kitty Foyle (1941), and with A Guy Named Joe (1943) under his belt. While blacklisted, both wrote under “fronts”, Trumbo responsible for the Oscar-winning screenplays for Roman Holiday (1953) and The Brave One (1956), Polonsky successfully switching for a time to television. Both productions proceeded with the need to keep secret the real screenwriters, Ira Wolfert fronting for Polonsky, author Howard Fast unknowingly doing the same for Trumbo.

The parallel tales of two ambitious producers dueling for supremacy and of two blacklisted writers fighting for survival make a thrilling read. At any moment, either production could be killed by revelations about the screenwriters, while the planned films faced a succession of what seemed sometimes insurmountable obstacles. Both movies pursued, for example, the same three stars – Laurence Olivier, Charles Laughton and Peter Ustinov. Martin Ritt, initial director for The Gladiators, dropped out while Anthony Mann, in the same position for Spartacus, was fired. Script problems dogged both pictures. Rivalry was conducted openly in the trade press while the productions clashed over the title. Even when Spartacus nudged ahead in the production process, the spiraling budget almost put paid to the endeavor, while The Gladiators hovered in the background, intent on capitalizing should, as appeared for a long time the most likely outcome, the Douglas film flop at the box office.

The third riveting element of this book is a scoop. The authors have located the original Polonsky screenplay for The Gladiators, believed lost for over 60 years, and so are able to contrast the different approaches to the subject of the Spartacus revolution. (In a separate volume, the entire screenplay has been published with annotations and critical commentary by Fiona Radford and background essays by MacAdam and Cooper). Koestler was a cult figure, far better known than Howard Fast, and has remained in the literary consciousness ever since his suicide in 1983. With The Gladiators failing to reach the screen, Polonsky remained under the Hollywood radar for several years before his career revived with the screenplay for Madigan (1968) and as writer-director of modern western Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here (1969) starring Robert Redford. The revelation that Trumbo had written Otto Preminger’s Exodus (1960) and the involvement of Polonsky in The Gladiators helped break the blacklist. Trumbo went on to enjoy a successful official comeback, biopic Trumbo (2105) depicting the tribulations he suffered as a blacklistee.

The book is available from Cambridge Scholars.