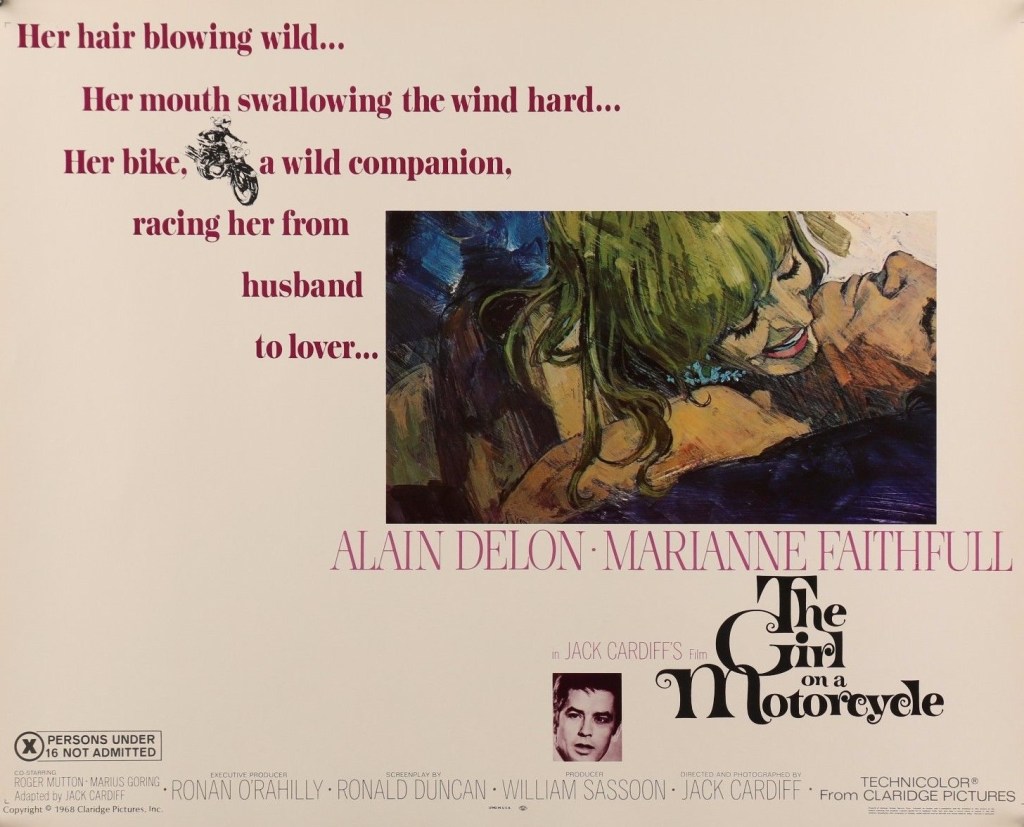

An erotic charge deftly switched this picture from the Hell’s Angels default of violent biker pictures spun out cheaply by American International. Where Easy Rider (1969) was powered by drugs, this gets its highs from sex. Rebecca (Marianne Faithful), gifted a Harley Davidson Electra Glide motorbike by lover Daniel (Alain Delon) two months before marriage to staid teacher Raymond (Roger Mutton), takes to the highways to find herself.

This ode to speed (of the mechanical kind) allows her to shake off her preconceptions and fully express her personality, beginning with the one-piece black leather outfit, whose zip, in one famous scene, Daniel pulls down with his teeth. The bike is masculine. “There he is,” she intones and there is a none-too-subtle succession of images where she clearly treats it as a male appendage.

She is both self-aware and lost. In some respects Raymond is an ideal partner since he respects her wild nature and gives her space, and she views marriage to him as a method of avoiding “becoming a tart.” In other words he represents respectability, just like her father (Marius Goring) who owns the bookshop where she works. But he is just too reasonable for her and, in reality, as she would inevitably discover that is just a cover for his weakness. The only scene in which she does not appear is given over to Raymond being tormented by young pupils who have him chasing round the class hunting for a transistor radio.

But Daniel is not quite up to scratch either. He believes in “free love”, i.e. sex without commitment and he is not inclined to romantic gestures and she knows she could just become another in a long line of discarded conquests should they continue. Raymond is a “protection against” Daniel and her ending up as an adulteress teenage bride and potential nymphomaniac. She seeks abandon not reality.

As well as sexy interludes with Daniel, her head is filled with sexual images, not to mention dabbling with masochism, in a dream her leather outfit being stripped off piece by piece by a whip-wielding Daniel, in a bar imagining taking off her clothes in front of the aged drinkers.

Jack Cardiff’s film is certainly an interesting meditation on freedom and sexual liberation at a time when such notions were beginning to take hold, but it suffers from over-reliance on internal monologue and Marianne Faithful’s lack of acting experience. Cardiff went straight into this from violent actioner Dark of the Sun (1968) and audiences remembering him from The Liquidator (1965) and The Long Ships (1964) would need reminded that he braced romance before in the touching and Oscar-nominated Sons and Lovers (1960). In that film he elicited an Oscar-nominated performance from Mary Ure, something that was unlikely here.

Pipe-smoking was generally the preserve of the old, or detectives, unless you were a young intellectual as Delon is here, but it does seem an odd conceit to force the actor into such a contrivance. Delon is accustomed to playing amoral characters, so this part is no great stretch, but, minus the pipe, he is, of course, one of the great male stars of the era and his charisma sees him through.

It was also interesting to compare Cardiff’s soundtrack to that of Easy Rider. Here, the music by Les Reed – making his movie debut but better known as a songwriter of classic singles like “Delilah” sung by Tom Jones – is strictly in the romantic vein rather than an energetic paeon to freedom such as “Born to Be Wild.”

Cardiff’s skill as an acclaimed cinematographer (Oscar-winner for Black Narcissus, 1947) helps the picture along and clever use of the psychedelic helped some of the sexual scenes escape the British censor’s wrath, though not so in the U.S. where it was deemed an “X”.