An absolute cracker, two blistering performances, tons of twists, and set to become the word of mouth hit of the year. Clever piece of counter-programming though nobody was foolish enough as I was to market it as an “AvataMaid” double bill and just as well because it would blow the overlong and rather tepid James Cameron epic out of the water.

This didn’t come trailing a whole bunch of accolades from a film festival and print critics have generally been snooty about it because they don’t know what the public really wants. Nobody thought to sell it as a woman’s picture either, but I saw this (three times now) in a packed theater on a Monday night and the crowd, mostly women, just lapped it up. Not because it was a hot romance or said something pious about motherhood or women’s issues but because, without giving away too much of the plot, it featured two tough cookies, almost a modern Thelma and Louise, who weren’t going to take it anymore.

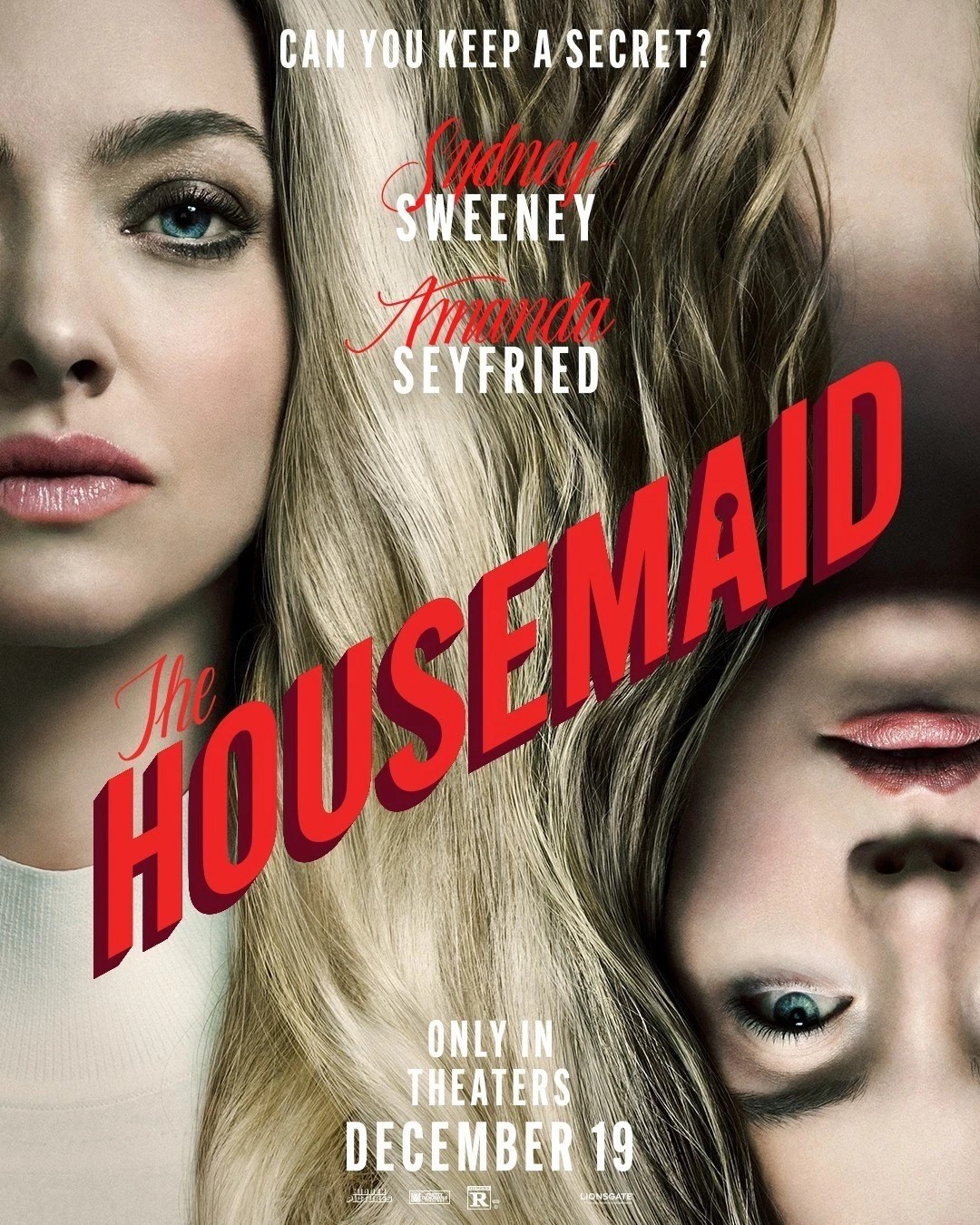

Nobody is what they seem. And the plot slithers from under you. I had no idea what this was about apart from the fact that the book was a bestseller. So I came in expecting the usual kind of story – new housemaid Millie (Sydney Sweeney) infiltrates millionaire’s household, dupes the loving mother Nina (Amanda Seyfried), seduces husband Andrew (Brandon Sklenar) and between them the lovers find a way of offing the wife and getting away with it.

I couldn’t have been more wrong. Nina, who seems initially a great employer (giving Millie $20 at the job interview to cover her time), turns out to be anything but. The house is a complete mess, she blames Millie for anything that goes wrong, seems on the edge of a constant nervous breakdown, and eventually sets her up to be arrested. And there’s no bonding with her daughter Cece (Indiana Elle), the most stuck-up obnoxious brat.

On the other hand not only is Andrew goddam handsome with a fabulous smile, he’s a saint to put up with his wife. Turns out she spent nine months in a psych ward after trying to drown her daughter in the bath. And that means should they split up, she’ll likely lose custody, and thanks to the ruthless prenup, will be penniless, and mad though she is who’d want to give up a millionaire lifestyle.

Turns out there’s a reason why Millie is so sweet and never stands up to her employer. She’s on parole and her parole conditions mean she needs a job and an address. To lighten her load, Andrew takes her side against the worst his wife can throw at Millie. Unwittingly, Nina is the architect of her own downfall, and it’s no wonder Andrew and Millie end up in bed and in love.

That’s not a twist, that’s what the audience was led to believe was going to happen. Twist Number One is Nina’s reveal is that Millie is serving a 15-year stretch for murder, still a third to go while out on parole. Twist Number Two isn’t that Nina also knows about the affair or even that as a result of another exceedingly malicious act by his wife that Andrew throws Nina out.

Twist Number Two is the best twist since The Sixth Sense (1999). Initially, it looks as if Nina is distraught with grief at losing her cushy number. But that quickly turns to being hysterical with relief at being freed of Andrew’s grip.

Why she would want to be free and what kind of trap Millie is walking into forms the second half of the picture and that’s a helluva ride, twist piling on twist, a combination of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and Jane Eyre (madwoman in the attic).

If we’ve had too much torture porn over the last couple of decades courtesy of Saw and its imitators, this raises the art to a new level. This is torture of the most subtle kind, at least initially, with one woman having to pull two hundred strands of hair (complete with follicles) out of her head.

But the best twist in this smorgasboard of twists is that it’s not Millie who’s walking into a trap, but Andrew. Millie was hired because she beat a man to death and Nina reckons she’ll be more than a match for her husband. I’m tempted to reveal more just for the pleasure on the clever tale, but I’ll let it go at that. And, as you have come to expect with this type of thriller, there’s a stinger in the tale. Here, there are two.

Sydney Sweeney (Eden, 2024) and Amanda Seyfried (Seven Veils, 2023) are both superb, and you have to take your hat off to Brandon Sklenar (It Ends With Us, 2024) for his transformation from saint to devil.

Neatly directed by Paul Feig (Another Simple Favour, 2025) and he does well to control the balance although obviously following the template laid down by screenwriter Rebecca Sonnenshine (Archive 81 TV series, 2022) adapting the Freida McFadden novel.

A welcome return to what Hollywood does best, beginning with a stellar story and then adding actors who can bring something to it, rather than the other way round, which usually results in a rambling tale only elevated by performance which is distinctly unsatisfying.

It says something for the quality of a thriller than even knowing all the plot points I was delighted to go back for a second look – and a third – and came away even more impressed at the way the pieces locked together.

Box Office Update: The Housemaid which cost only $30 million is already into hefty profit with $200 million, more than double the take of critical fave Marty Supreme (costing $90 million). Plus it’s been so successful there are plans for a sequel.