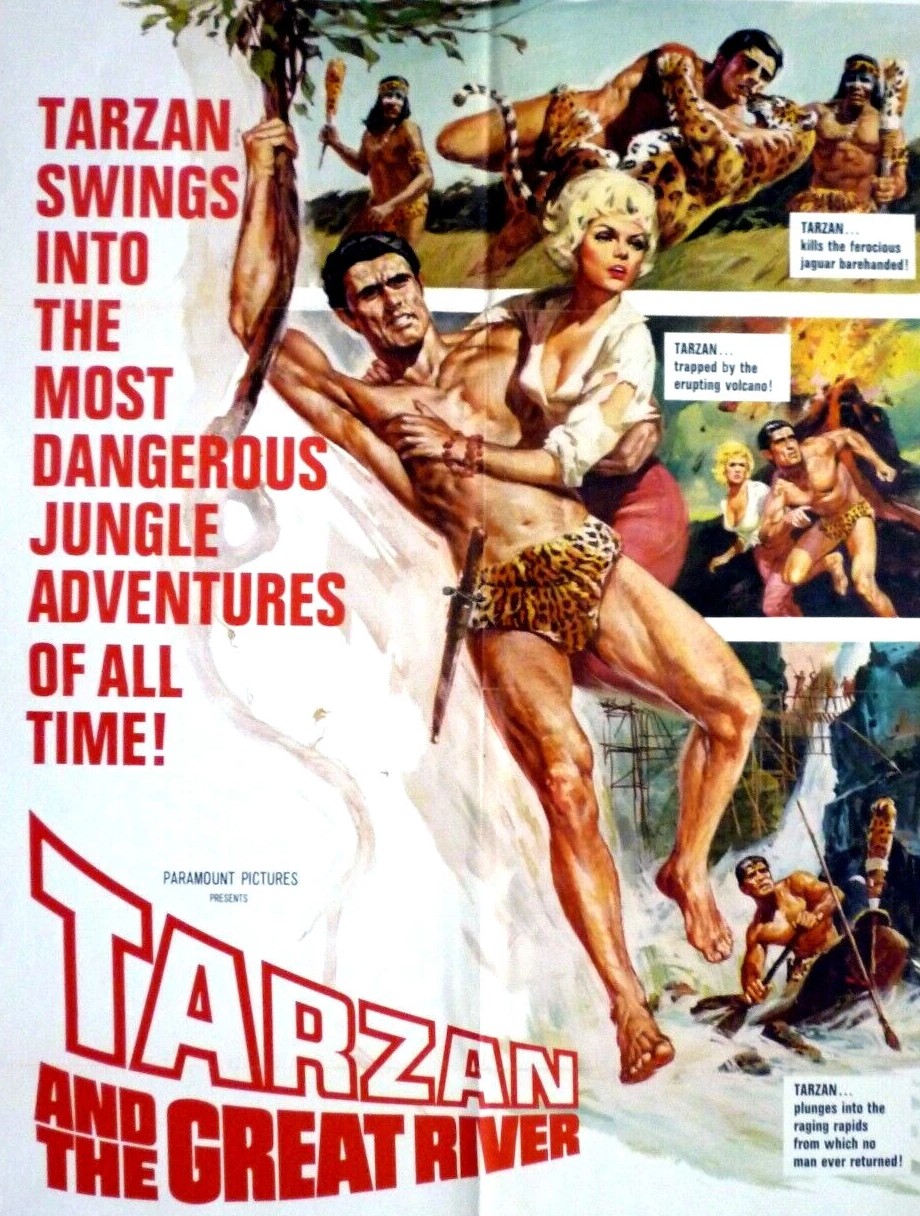

Tarzan (Mike Henry) has been repurposed as an international adventurer dropped into trouble spots an ocean away from his African roots. He’s the male equivalent of the bikini-clad females peppering the espionage genre, kitted out in only a loincloth, torso kept bare for the titillation of the ladies. And just like the James Bond series, there’s an evil personage, and while not in the business of taking over the world still wanting to dominate a good chunk of it in South America. Barcuna (Rafer Johnson), espouses the Jaguar death cult, terrorizing villages and enslaving their inhabitants for the purpose of searching for diamonds.

To fill out the narrative, a good chunk of the picture is spent with riverboat Captain Sam Bishop (Jan Murray) and the native orphan Pepe (Manuel Padilla Jr.) he has unofficially adopted and their comic shtick mostly involving the older man cheating at cards is all we’ve got to keep the drama going until the female in distress, Dr Ann Philips (Diana Millay), turns up. But, as you know, Tarzan is no lothario, unlike his colleagues in the espionage department, so we don’t have to wonder if romance is going to raise its ugly head.

In the meantime the producer has scoured the vaults for stock footage and clearly is of the opinion that if you can transplant Tarzan from his natural African habitat you can do the same with hippos. Tarzan wrestles a lion and a crocodile and despatches Barcuna’s henchmen on land and in the river, swimming underwater and tipping over canoes to do his part in keeping the local crocodiles well-fed.

Barcuna, meanwhile, roasts alive anyone caught trying to escape, though he allows the good doctor to escape either because he’s not partial to blondes or he reckons she won’t be much good at hunting for diamonds or, as suggested once he burns her village, because he wants her to let everyone know that he’s the big cheese around here.

There’s the usual plague subplot. Dr Millay is waiting on the arrival of a vaccine to fight a new plague – Bishop is delivering the stuff – but she has a job getting the natives to accept inoculation and it’s only when Pepe offers himself as a guinea pig that the others queue up.

Devoid of the gadgets, speedboats and fast cars of the espionage genre, Tarzan relies on the speed of his legs as if he was auditioning for the Tom Cruise role in Mission Impossible or that of Liam Neeson in the Taken series. There’s a spectacular fight between Tarzan and Barcuna for the climax.

Harmless stuff, as innocuous as the others in the trilogy featuring former football player Mike Henry (The Green Berets, 1968). They were filmed back-to-back in 1965 and released at the rate of one a year from 1966. This was the third time producer Sy Wintraub’s had reinvented Tarzan. He had previously shepherded home a pair – starting with Tarzan’s Great Adventure (1959) – starring Gordon Scott. Jock Mahoney inherited the mantle with Tarzan Goes to India (1962) and lasted for one more adventure.

This was the last of a quartet of outings with Tarzan for director Robert Day (She, 1965). Written by Bob Barbash (The Plunderers, 1960).

Perfect Saturday matinee material.