The third act of this heavily-favored Oscar contender is so demented I half-expected Mark Wahlberg from Flight Risk (2025) to come charging in through the woodwork. So, spoiler alert and all that jazz, I’m going to tell you what all the critics, determined to shove this into Oscar pole position, have kept hidden.

The dramatic climax, if that’s the right word, is a male rape. Our hero Laszlo (Adrien Brody), by this point a bit addled what with his alcoholism and heroin addiction, on a trip to the marble quarries, while extremely addled, is raped by multi-millionaire patron Van Buren (Guy Pearce), previosuly inclined towards the philosophical and intellectual rather than showing any hint of apparent violent or for that matter homosexual tendencies.

This rape sets Laszlo off an inexplicable series of tirades against all and sundry which puzzles said all and sundry until his crippled wife Erzsebet (Felicity Jones), until now in a wheelchair and equally inexplicably now on her feet, albeit with the help of a walking frame, turns up at a Van Buren dinner party to point the finger. At which point, understandably, the money is pulled from the architectural marvel being built, though not before we see, in another inexplicable sequence, its one genuine marvel, the way light from outside lights up a cross on the altar.

Just to round everything off, just when the movie is headed, what with said millionaire pulling the plug, for one of those sad endings when said architect is left high and dry and the building set to be an unfinished folly and Laszlo possibly heading for a mental institution or the breadline, genius unrecognized, we are presented with a coda, and with a swish of the directorial magic wand, it turns out that instead Laszlo went on to have a magnificent career, so much so a major exhibition is launched in his lifetime.

So, what was a pretty engrossing drama, with, for probably the first time on celluloid, an understanding of what goes on in the mind of a genius builder given the same credence as the evolution of an artist of the painting or music variety (witness the recent A Complete Unknown), turns, with several fell swoops, into an oddity, one which critics are desperately trying to salvage to position it, as I mentioned, as not only the Oscar favorite but as a contemporary version of Citizen Kane.

In an ordinary theater this makes not the slightest difference.

These aren’t the only inconsistencies. Completely broke, living in a single room, at the end of the 1940s, after our Holocaust refugee has become an American immigrant, he manages to scrape enough money together to hire/buy a movie projector and hire/buy a porno flick. And I’m still getting my head round the building of a “community” endeavor, part-funded by the community, being constructed on a remote hill several miles away from the community it is meant to serve. Not to mention, Laszlo being able to afford a packet of smokes while queuing at a soup kitchen and while raging against the machine that a young child is left without even a slice of bread doesn’t go and buy a loaf of bread for the starving child instead of a packet of cigarettes for himself. And if you’ve ever met anyone who has a fabulous library, the last thing they want is the books hidden away, even from the dangerous sun, and even to allow an architectural genius an architectural flourish.

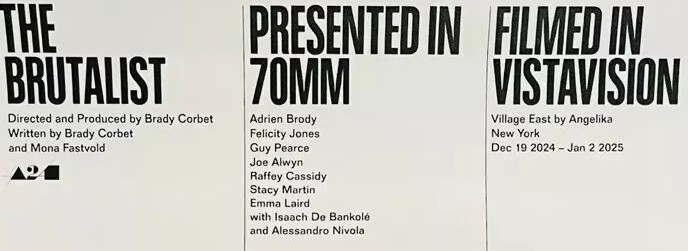

Certainly, director Brady Corbett (Vox Lux, 2018) wants to have his cake and eat it, so as well as Holocaust references, we are shown grinding American poverty before getting back on track to tell the story of artistic genius and the financial obstacles, considerably more in the building business than painting or writing a tune, it must overcome.

So why everyone is trying to position this as the Oscar fave is because despite these deficiencies, the first two-thirds of the picture present a very absorbing and ambitious drama. While you’re scarcely going to find a scene that genuinely sticks in the mind, if we are putting Corbet in the Scorsese, Nolan, Scott, Spielberg category, the overall effect is certainly effective and the look distinctive. And while the male rape is going to divide audiences, there is an unusual stack of sexuality elsewhere – his cousin Attila (Alessandro Nivolo) is overly affectionate even given the overly expressive male camaraderie of European countries and likes to sashay around in an apron. On landing in the U.S., one of Laszlo’s first acts is to hook up with a hooker, and there’s a distinct frisson of sexuality in the Attila household, while the crippled wife finds the sex act alleviates her pain.

What brings this alive and gives it substantial heft are the three male performances. Adrien Brody, proof that one Oscar win (for The Pianist) doesn’t open as many doors in Hollywood as you’d expect, is immense, given a wide panorama of feelings to play with, completely engaging and more important, believable, all the way through. But Guy Pearce has equally drifted in a tsunami of supporting roles or top-billing in small pictures and he is superb as the restrained businessman finding expression through closeness to art. And Alessandro Nivolo (Amsterdam, 2022), also somewhat in need of acting redemption, has a brilliant turn as the sinuous cousin.

I didn’t find this as bum-numbing (even while sitting in the worst seats in the world – at least a quarter of a century old by my count, yeah that old – in my local arthouse) as I expected – the first time I looked at my watch there was only 25 minutes left to go. It wasn’t the length that made me antsy but the drive into off-piste territory in the third act, as if Corbet had no idea how to finish the picture.

Despite my reservations, and there are, as you can see, many, this is worth seeing, though maybe you might want to skip out at the conveniently-placed intermission.