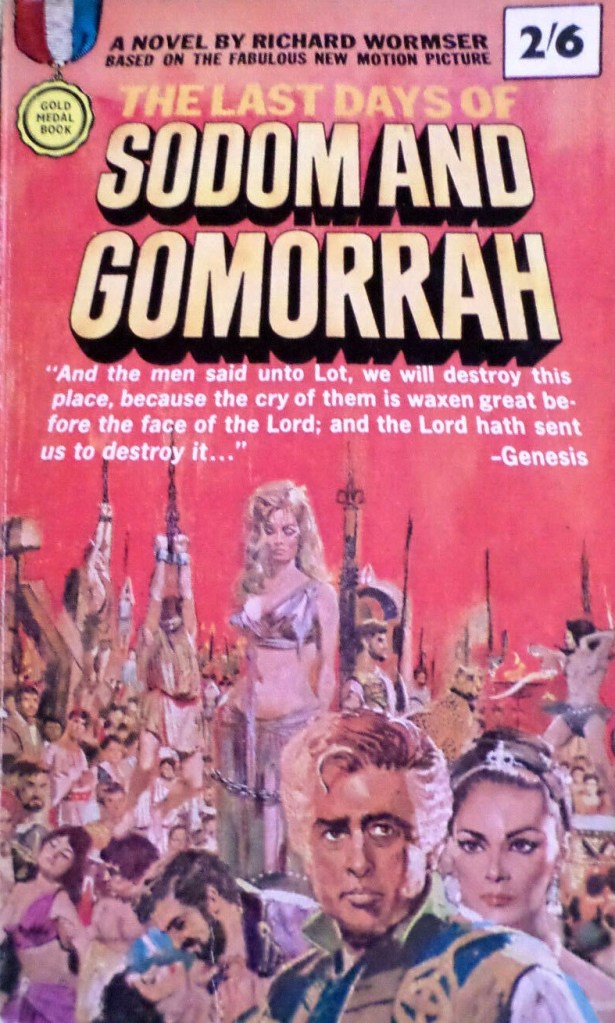

Taking a Biblical tale as a starting point veteran director Raoul Walsh (White Heat, 1949) stirs up heady brew of intrigue, rebellion, politics and romance. Returning home victorious, King Ahasuerus (Richard Egan) discovers his wife Queen Vashti (Danielle Rocca) has committed adultery and that his minister Klydrathes (Renato Baldini) has been squeezing the people blind with punitive taxes, hanging them for non-compliance.

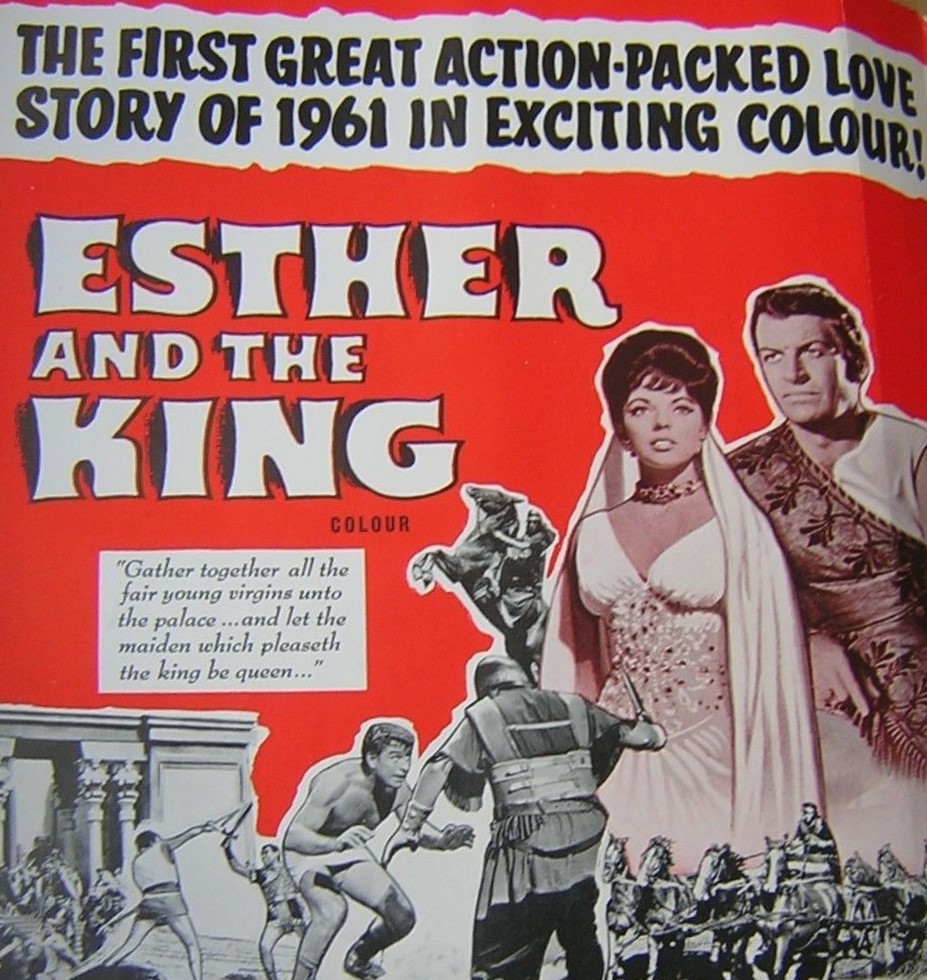

Casting his wife aside, the king seeks a new bride. Since he has conquered all the known world except Greece, marriage to make a political alliance is not an option, so, given women are treated as mere chattels and the king is all-powerful, all the likely virgins are rounded up including Hebrew Esther (Joan Collins) on her wedding day.

Her husband-to-be Simon (Rik Battaglia) kicks off, attacks Klydrathes and becomes a wanted man. The queen’s lover and the king’s chief minister Prince Haman (Sergio Fantoni) attempts to fix the bridal selection, inserting his hardly-virginal choice Keresh (Rosalba Neri) into the proceedings while attempting to murder clear favorite Esther. When that fails, Haman plots to usurp the crown. With the Hebrews facing possible annihilation, Esther is put in the position of giving in to the kind in order to save her people. As her serenity soothes the savage beast, her initial hate turns to growing attraction.

Meanwhile, Simon is on a rescue mission and Prince Haman cooks up a devilish plot that will see the Hebrews blamed for passing on military secrets to the king’s enemies. Naturally, all hell eventually breaks loose.

More a drama than a typical big-budget DeMille offering, with battles taking place off-screen action is limited to a few chases and skirmishes. There is a fair amount of sin on show what with a tribe of concubines at the king’s disposal, a whipping, a striptease by Vashti in a last gasp attempt to win back the king, some very seductive dancing routines by female slaves who, at times, look as if they were coached by Busby Berkeley. Substantial amounts appear to have been spent on costumes and production design, so historical atmosphere is well captured. Once you realise there’s not going to be any kind of big battle or major action center piece common to the Biblical genre, it’s easy to sit back and enjoy the political machinations, the initial torment of Esther, introduced as a rebellious soul, and the king, more at home with soldiers, shaking off his despondency at marital betrayal as he responds to Esther’s coaxing.

Richard Egan (300 Spartans, 1964) is a thoughtful king, showing very little temper, possibly because he doesn’t need to with everyone, beyond the conspirators, cowering in his presence. Regal and stately suits him fine rather than the more common explosions were accustomed to seeing from people in that line of work. The top-billed Joan Collins (Seven Thieves, 1960) has a difficult role. Normally, you would expect expressions of passion or depths of anguish, but the rebellion she displays at the start soon disappears when she enters the palace and is helpless to change the situation except by, initially against her will, accepting the king’s desires. In that sense, her portrayal is understandable but the understated performance gets in the way of a woman who is supposed to be devastated by the loss of her husband and then trapped by the needs of her people into making the marriage.

Sergio Fantoni (Von Ryan’s Express, 1965) excels as the spurned lover and Rik Battaglia (The Conqueror of the Orient, 1960) as the schemer. Rosalba Neri (Top Sensation, 1969) and Danielle Rocca (Behold a Pale Horse, 1964) both make striking appearances. Look out also for Gabriele Tinti (Seven Golden Men, 1965).

It was the end of the line for Irish actor Dennis O’Dea (The Fallen Idol), making his final film, and also, at least temporarily, for Joan Collins. She was coming to the end of her seven-year Twentieth Century fox contract but fell out with the studio after being rejected for Cleopatra, and on the evidence here you can see why. She been top-billed in The Sea Wife (1957) above Richard Burton and The Wayward Bus (1957) above Jayne Mansfield, but gradually fell down the pecking order. After leaving Fox, she only made five more films during the decade. Director Raoul Walsh made only another two.