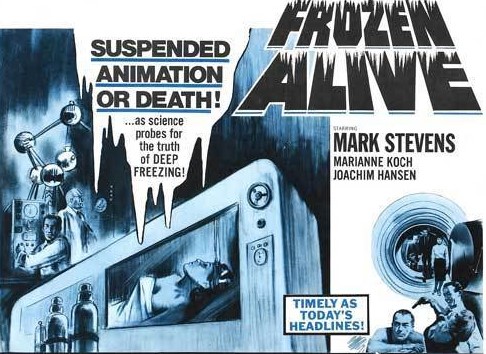

Sometimes the stars fail to align, initial promise fizzling out. Mark Stevens, rising post-war star, top-billed in film noir The Street Has No Name (1948) and Between Midnight and Dawn (1950), paired with Olivia de Havilland in The Snake Pit (1949), seemed all set for major stardom. No go. By the end of the 1950s he was mostly seen in low-budget westerns, and too few of them. September Storm (1960) was his first picture in two years. He had tried his hand at direction, but landed in B-movie hell with titles like Escape from Hell Island (1963) and after a bit part in Fate Is the Hunter (1964) hightailed it to Germany for this.

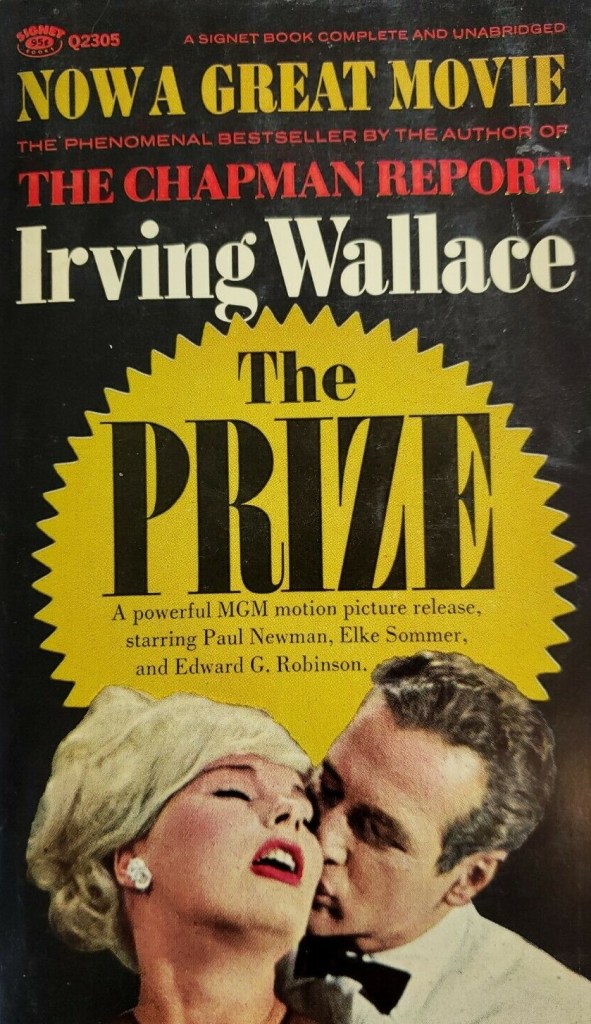

Not quite the sc-fi or noir number it says on the tin, more an exploration of personal and professional jealousies in the scientific community. You probably didn’t know the World Health Organization ran a Low Temperature Unit engaged in cryogenics experiments. Maybe they did, this being promoted as a timely movie.

Dr Overton (Mark Stevens) along with lab partner Dr Wieland (Marianne Koch) are on the verge of a breakthrough in their cryogenic experiments with monkeys. Although she has a lover Tony (Joachim Hansen), his unfaithful alcoholic journalist wife Joan (Delphi Lawrence) is jealous of his success and of Wieland and dreads leaving the fast lane for life in the country and potential motherhood.

Professional jealousy results in the successful scientific team being split up, so before that can be actioned, Overton decides to embark on a human experiment with himself as the guinea pig.

All the tension of watching an inert frozen human being relies on wondering whether he’s going to wake up and will he have all his working parts, brain especially. So, just to heighten that tension, Overton could face a murder charge when he does emerge. And Wieland, in love with him, has to decide whether it’s better to let him die than go to prison.

The crime aspect is something of an oddity. The time element puts Overton potentially in the frame. And there’s a definite Hitchcockian element to the death, that in one sense robs it of tension, but in the other jacks it up to eleven. Because what we know but Wieland doesn’t is that Joan died by accident, playing with the gun of her lover.

So not only could an innocent man go to jail in the first place, stacked up against him his potential anger at potentially discovering his wife has a lover, but Wieland could let him die only to find out afterwards that he’s innocent all along.

It’s a good job Joan did die because she was stealing the picture. But even being soused in booze doesn’t dampen her zest for life, the kind of woman whose life mostly exists in cocktail bars and smart parties, dressed to the nines, showing enough cleavage to annoy her husband but tease potential suitors, and with enough toughness to dump any lover that gets too close. She’s sassy fun and married the wrong dull guy.

And she’s smart enough with her “intelligent anticipation” to figure out that husband is soon going to cosy up to lab buddy. Overton’s boss notices the signs when he’s not too busy covering his own back. “You sit on the fence and if someone makes a fuss later I take the rap.”

The Mind Benders the previous year covered similar territory but concentrated on the post-experiment after-effects, so this is almost a prologue to that, and interestingly, setting Joan aside, delivered with almost a British stiff upper lip, secret passion kept under wraps, lust revealed in lingering looks, while the cut-throat elements of ambition are played out under the guise of a civil service mentality.

Not quite what you’d expect from the title, but then it’s kind of a cul de sac in sci fi terms, as it’s generally the awakening that produces the problems and this doesn’t go there. But still a decent watch. British actress Delphi Lawrence (Farewell Performance, 1962) steals the show but the simmering turn from Marianne Koch (A Fistful of Dollars, 1964) comes close. Mark Stevens doesn’t have as much to play with and he’s pretty much kept his emotions tamped down up to this point so hardly going to let rip now. Wolf Rilla (The Secret Ways, 1961) has a small part.

Bernard Knowles (Hell Is Empty, 1967) directed television writer Evelyn Frazer’s only screenplay. You might dwell on the irony that Delphi Lawrence’s star turn here led to nothing as much as Mark Steven’s career dwindled.

Something of a cult possibly because it’s hard to find.

Watchable.