Very tricky home invasion thriller. And not just from the narrative perspective and my guess is you’ll work out what’s going on long before the end, but that’s deliberate, you’re meant to, because the final twist isn’t plot but emotion, unexpected pent-up release.

Deftly directed by George Englund (The Ugly American, 1963), distinguished camerawork, long shot and overhead put to exceptional use. Biggest surprise is Stuart Whitman (Rio Conchos, 1964) taking the acting plaudits from Oscar-winner Joanne Woodward (A Fine Madness, 1966).

Slightly throws you because the interesting questions it asks about the treatment of the insane and the rehabilitation of criminals could, in retrospect, just be a contrivance to serve the plot. Basically, it’s a one-set show but thrumming continually in the background is a working water mill, the location being an English mill house belonging to American Molly (Joanne Woodward) awaiting the return of her husband from a business trip to Amsterdam. She’s got quite the hots for her lover because she’s planning to greet him at the door all decked out in a swimsuit.

But that’s in the future, takes 20 minutes of this exceptionally short picture (just 78 minutes) before we get to her. First of all, we’ve got the set-up. Confined within an asylum surrounded by high electric fences is wife killer Alex (Stuart Whitman), five years into his stretch, whom resident psychiatrist Dr Fleming (Edward Mulhare) not only believes is sane but also innocent, the convicted man having no memory of killing his wife and, as it later transpires, no motive.

The asylum officials ain’t so crazy on Fleming’s theories but by this time the good doctor has fed Alex a line, a loophole in English law dating back to the Victorian Lunacy Act, which, bizarre though it may seem, allows a man who escaped from an institution and remained free for 14 days to be permitted a re-trial.

When Fleming’s request for leniency is turned down, Alex escapes, heads for the river to elude hound dogs picking up his scent and ends up at the mill. The siren has sounded so everyone in the village is on the alert. From his cell high on a hill, Alex has previously scoped out the village, and with the help of Fleming, identified various houses, and from his own observations learned about the community, such as that the mill owner is handy with a shotgun, killing rabbits with abandon.

though the characters skewed older in the stage version,

Margaret Lockwood approaching 50, Derek Farr just past 50.

So it’s Alex who is greeted by the swimsuit. And then it’s the familiar duel of minds. Though we’ve just seen him knock out the doctor and an electrician, when Alex enters this house he’s a changed man. Sure, he has the shotgun but he’s planning to only hide out for a night, till the search expands away from the village and he can sneak through the gaps and hide out for the fortnight necessary to implement the loophole.

We know he’s not exactly a maniac, or a tough guy in the Lee Marvin mold, because we’ve seen what a sensitive and intelligent character he is through his conversations with Fleming, and he’s trusted enough by the officials to be allowed an axe to chop wood. But Molly doesn’t know that. She’s expecting a maniac and is thrown when he’s calm and gentle, not to mention tender.

He seems to shed nine lives when he enters this realm of domestication. She’s not half as confident as her sophistication might suggest. Her marriage has not brought her the comfort or the love she expected. The countryside is shrouded in fog, so her husband’s not going to be back till morning, which removes one complication, but adds another, a growing feeling that they are kindred souls, lost and vulnerable.

His story appears to make sense to her and when he espies a corpse trapped on one arm of the wheel it’s she who comforts him when he thinks its imagination run wild and then in the more obvious sense they console each other.

Comes the twist. That was a real body. Her husband.

This where you think. Uh-oh. The old story of the femme fatale and the patsy and you wonder were any of her feelings true or was she just acting the part to gull him. So, when the police and Dr Fleming arrive, the finger is most obviously pointed at a man who has no memory of killing before. Remember, this is in the days when the simple detection methods available now would have easily cleared him, so you have to go with the flow.

When Alex defends himself and declares that they slept together and sounds so utterly confused, one of the cops, for no desperate reason it has to be said in the absence of the usual clues on which we rely, thinks something foul is afoot.

And it’s her who confesses. She had expected a maniac not a gentle man who touched her soul in a way that neither husband nor lover, Dr Fleming, managed. Totally turns the picture on its head. And instead of the usual plethora of clever sleuthing, we have a resounding emotional climax.

Full marks though to George Englund, not just for the outstanding use of the camera, creating distance between characters even in intimate situations, one great shot where through separate windows Alex and Molly stare at each over the rolling watermill, and to offset the tension some excellent comedy as the Yank comes to terms with British tradition after a death. He cleverly opens up the original stage play by Monte Doyle, and there’s a strong hint of irony in the opening section which sees a car-load of kids point to two loonies on the hill. We quickly learn only one is designated as such, Alex, but the other one, the sane one, Dr Fleming, turns out to be every bit as mad.

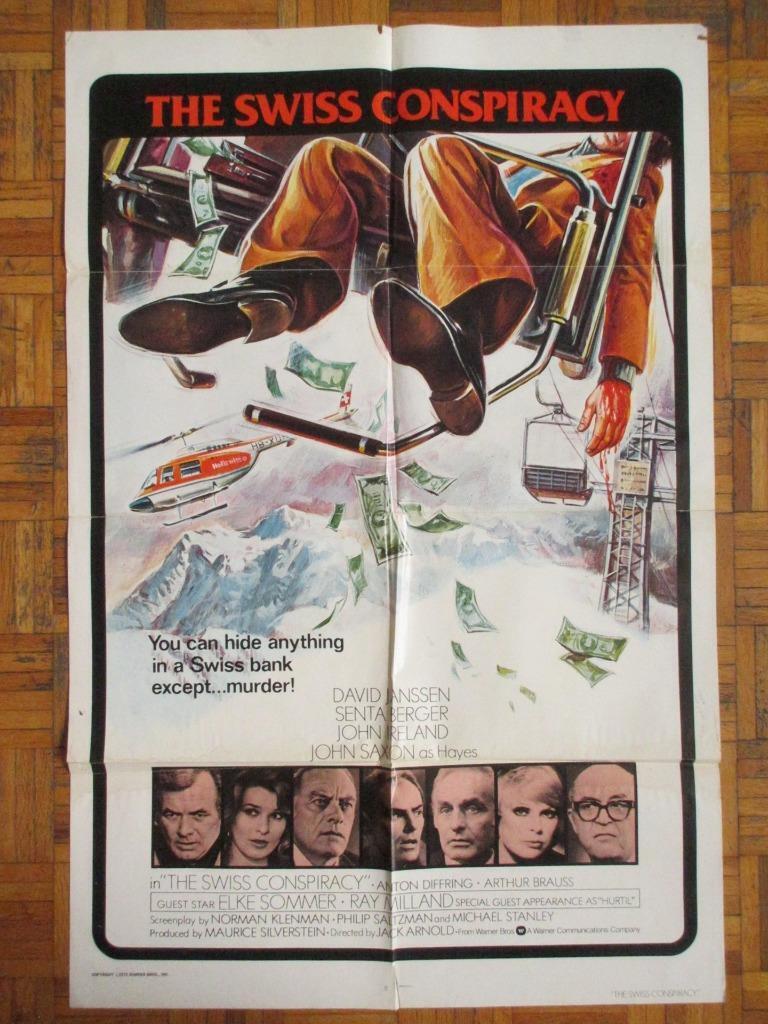

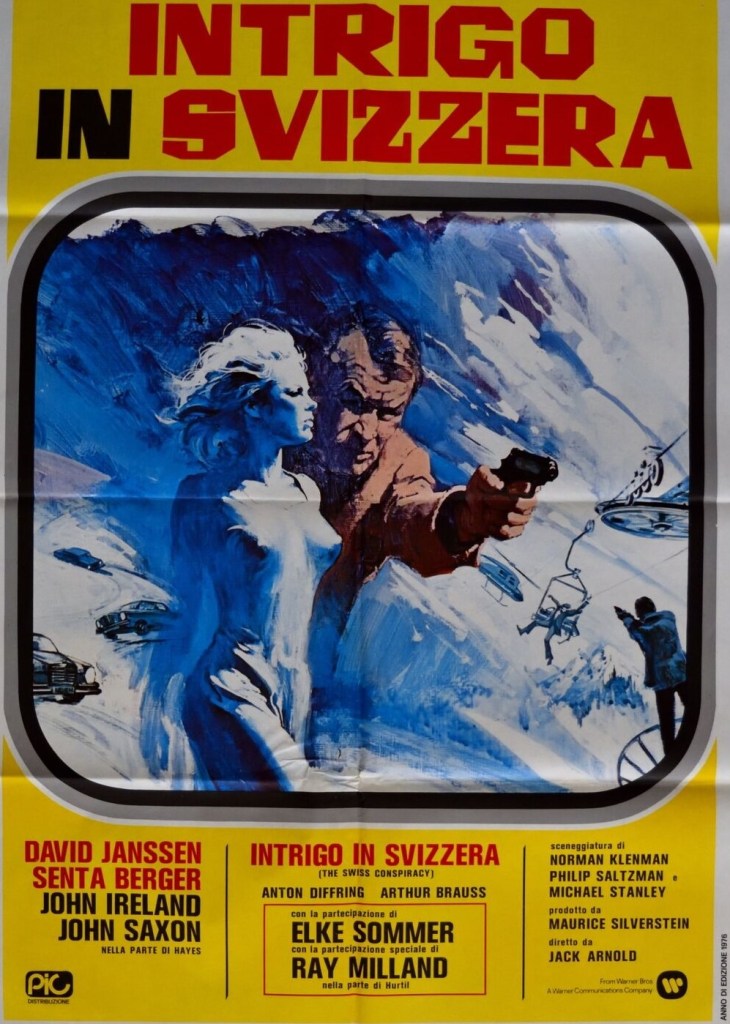

But this is Stuart Whitman’s tour de force. He had earned an Oscar nomination for The Mark (1961) but appeared to exert more box office appeal when he went all square jaw in action pictures. I’m not the first observer to mention that one of the key points in a performance is an actor’s reaction to their surroundings. Like you or me, they should look round. I noted that with David Janssen in The Swiss Conspiracy (1976). But here is an even better example. When Alex sees the lounge and all the elements of domesticity, he’s not just having an ordinary look, he’s soaking it up and it’s taking him back to the life he lost, one he can’t understand why it was taken away from him. You look at a modern film. The camera does all the work. The director uses a habitat to guide you into the mind of the inhabitant but rarely, as in the old days, to allow reflection on the part of a visitor.

There’s a huge range of emotion for Whitman to pack in, not to mention a convincing British accent, and he does it all. Woodward nearly steals the picture away from him with that final, unexpected, scene. Molly knows that by confessing she’s about to lose the love of her life and if she doesn’t be condemned to live with a man who doesn’t come close.

In the stage play Molly was clearly the top role and always attracted the bigger star. Same here, Woodward is billed above Whitman. The last scene is a peach for any actress. But Whitman’s is the more difficult role. Should maybe be a split decision but I come out for Whitman.

Superb minor gem.