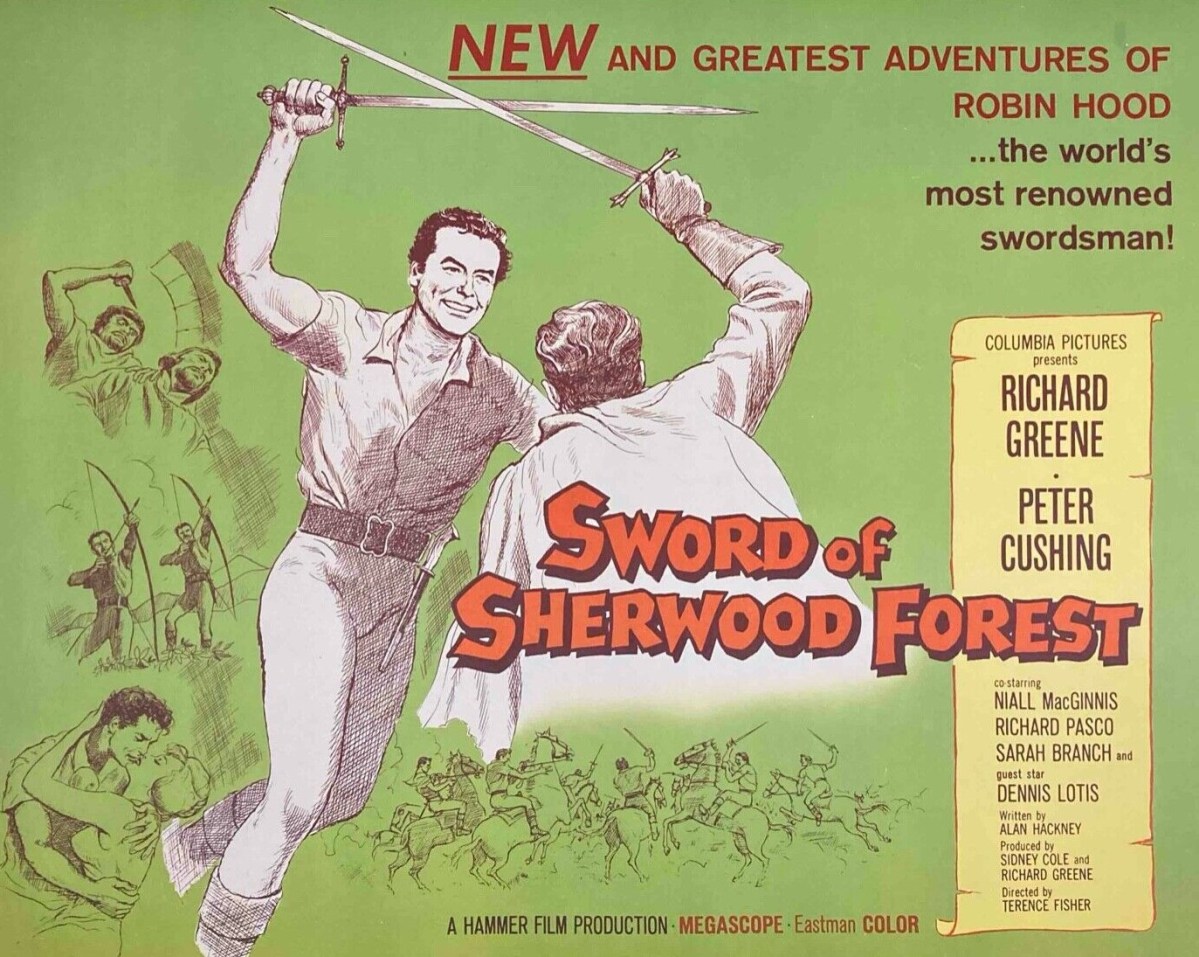

The last swashbuckler to cut a genuine dash was The Crimson Pirate (1952) with an athletic Burt Lancaster romancing Virginia Mayo in a big-budget Hollywood spectacular. The chance of Hollywood ponying up for further offerings of this caliber was remote once television began to cut the swashbuckler genre down to small-screen size. Britain’s ITV network churned out series based on Sir Lancelot, William Tell and The Count of Monte Cristo and 30-minute episodes (143 in all) of The Adventures of Robin Hood. So when Hammer decided to rework the series as Sword of Sherwood Forest their first port-of-call was series star Richard Greene.

And to encourage television viewers to follow the adventures of their hero on the big screen, Hammer sensibly dumped the small screen’s black-and-white photography in favour of widescreen color and then lit up the canvas at the outset with aerial tracking shots of the glorious bucolic greenery of the English countryside. Further temptation for staid television viewers came in the form of Maid Marian (Sarah Branch) bathing naked in a lake. Robin Hood is soon hooked.

Two main plots run side-by-side. The first is obvious. The Sheriff of Nottingham (Peter Cushing) is quietly defrauding people through legal means. The second takes a while to come to fruition. Robin Hood is hired by for his archery skills by the Earl of Newark (Richard Pasco) – he shoots a pumpkin through a spinning wheel, a moving bell and a bullseye through a slit – before it becomes apparent he is being recruited as an assassin. Oliver Reed and Derren Nesbitt put in uncredited appearances and the usual suspects are played by Niall MacGinnis (as Friar Tuck) and Nigel Green (as Little John).

There is sufficient swordfighting to satisfy. Director Terence Fisher (The Gorgon, 1964), more at home with the Hammer horror portfolio, demonstrates a facility with action. Richard Greene (The Blood of Fu Manchu, 1968) makes a breezy hero and Peter Cushing (The Gorgon) resists the tmeptation to camp it up. Screenplay honors went to Alan Hackney (You Must Be Joking! 1965).

Six years on from Sword of Sherwood Forest, the challenge of reviving a moribund genre proved too much for A Challenge for Robin Hood but this second Hammer swashbuckler is a valiant and enjoyable attempt. More in the way of an origin story, this explains how a nobleman turned into an outlaw and how the merry band was formed. For in this tale Robin Hood (Barry Ingham) is a Norman nobleman framed for murder, Will Scarlet (Douglas Mitchell) and Little John (Leon Greene) are castle servants – also Normans – while Maid Marian (Gay Hamilton) is in disguise. Some liberties are taken with the traditional version – there is no fight with Little John, instead, as noted above, they are already acquainted.

There are a couple of excellent set pieces and although the swordfights are not in the athletic league of Errol Flynn they are more inventive than the previous Hammer outing and there is enough derring-do to keep the plot ticking along. Robin’s cousin Roger de Courtenay (Peter Blythe) is the prime villain this time round, the sheriff (John Arnatt), although involved up to the hilt at the end, content to offer acerbic comment from the sidelines.

When Robin and Friar Tuck escape the castle by jumping into the moat, Will Scarlet is caught and later used as bait. Meanwhile Robin’s archery prowess and leadership skills have impressed the Saxon outlaws hiding in the forest and he takes over as their head. But there are clever ruses, jousting, Robin disguised as a masked monk, torture, and a pie fight.

Director C. M. Pennington-Richards had some swashbuckling form having helmed several episodes of The Buccaneers and Ivanhoe television series but his big screen experience was limited to routine films like Ladies Who Do (1963) with Peggy Mount. This was a departure for scriptwriter Peter Bryan, more used to churning out horror films like The Brides of Dracula (1960) and The Plague of the Zombies (1966), and he has invested the picture with more wittier lines and humorous situations than you might expect.

It’s certainly an escapist holiday treat and unless compared to the likes of the Pirates of the Caribbean or the classic Errol Flynn adventure it stands up very well on its own.