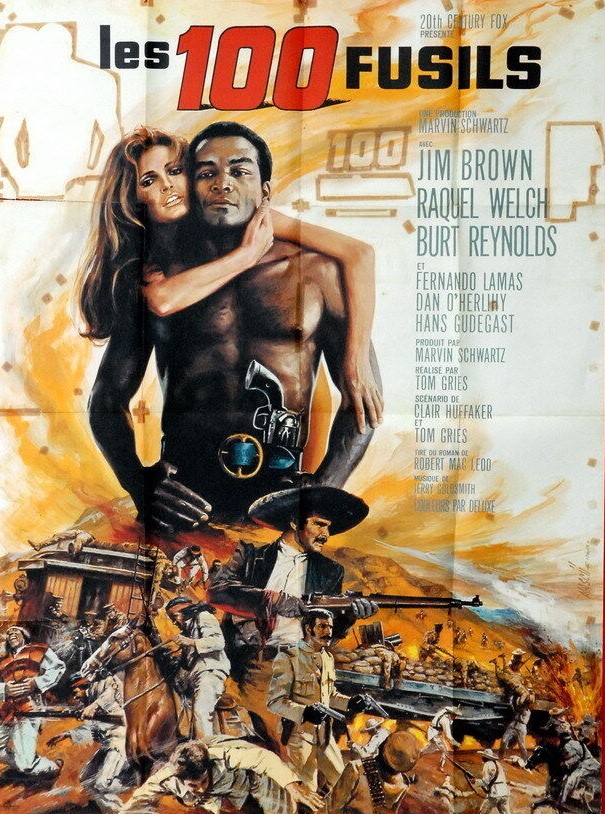

Highly under-rated but effective western that cemented Raquel Welch’s position as the queen of the genre, established Jim Brown as the first African American action star, scored points for its parallels with Vietnam, and provided the only image of the actress to rival that iconic fur bikini.

Arizona lawman Lyedecker (Brown) arrives in Sonora, Mexico, in 1912 on the trail of half- breed bank robber Yaqui Joe (Burt Reynolds). He finds the Mexican army callously executing Yaqui Indian rebels. To prevent further killing, Joe creates a diversion, which, while failing, permits the captured Sarita (Raquel Welch) to escape. The $6,000 Joe stole buys the titular 100 rifles to help the rebel cause.

Helped by Lyedecker, Joe escapes, picking up Sarita on the way. Both Lyedecker and the Mexicans are in pursuit, and the Mexicans soon recapture Joe and Lyedecker, who is now viewed as a rebel. Sarita again escapes. Lyedecker and Joe are returned to the garrison where the Mexicans have taken possession of the rifles. Just as the pair are put in front of a firing squad, Sarita, leading a group of rebels, frees them and steals the weapons.

In retaliation, the Mexicans attack a village, slaughtering the inhabitants and taking the children as hostages. At night, Lyedecker, Sarita, Joe and some rebels capture the garrison before the soldiers return, freeing the children. Lyedecker has been injured in the battle; after Sarita binds the wound, they make love.

When they take the rifles to the rebel stronghold, they discover the rebel leader is dead. For no particular reason, the rebels elect Lyedecker their new “generale.” Seizing a Mexican troop train is pitifully easy once Sarita creates a diversion by taking a shower under a water tower. The empty train is sent cannoning into the town and in the ensuing battle Sarita is killed. Yaqui Joe takes over leadership of the rebels while Lyedecker rides home.

While the capture- escape-chase-capture formula is overdone, the movie’s biggest structural problem is Yaqui Joe, clearly turned into a drunk to avoid becoming a romantic encumbrance for Sarita, leaving the way clear for Lyedecker. His other contributions are to brawl with Lyedecker and try to get the American to give up his quest and stay and help the rebels. There are other unnecessary characters and touches. We know it is a modern western because a motor car is involved as there would be in The Wild Bunch. The sole purpose of a German military adviser Von Klemme (Eric Braeden) is to act as a sounding board for Gen. Verdugo (Fernando Lamas), whose actions in any case speak louder than words. Railroad magnate Grimes (Dan O’Herlihy) represents equally callous big business. When Americans get drunk in westerns, that usually leads to fisticuffs, but when Indians knock back the liquor in 100 Rifles they act like clichéd drunken Indians, tearing up the town, looting and destroying anything in sight.

These reservations apart, the film has a great deal to recommend it. On the whole, it is well directed, although without much of an eye for landscape. Sarita, wearing a red headscarf, thus continuously color-coded, is accorded the greatest emotional depth, haunted by guilt for sacrificing her father in the name of freedom: “I helped him to die.” But she has another weapon at her disposal: her body. When captured, she distracts a soldier with sight of her breasts before stabbing him, the shock in her eyes suggests this is the first time she has killed a man.

Although the narrative advocates her as feisty leader from the start, this scene, and in particular her reaction, suggests otherwise. More than capable of taking care of herself, it is she, and not the two stronger men, who effects an escape. When she organizes the rescue of the two men, she’s more interested in the guns than them. But when it comes to children, they take precedence.

The genocide theme, pertinent both to American treatment of its own indigenous Native Americans and to the current war in Vietnam, is raised. It is more trouble than it’s worth for Gen. Verdugo to clear the Indians from their lands and ship them elsewhere, as the Americans had done when putting Indians onto reservations. Verdugo has few compunctions. Unlike in The Wild Bunch and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, here the railroad is a tool of control. Trains loaded with troops and guns (including Gatling guns, also seminal to The Wild Bunch) and artillery can travel with ease across alien territory to keep the inhabitants in check. As exemplified by Grimes, railroads also represent the intrusion of big business into politics and ordinary lives, and the railroad man, while concerned that Lyedecker’s possible execution could jeopardize U.S.- Mexican relationships and, by extension, possible halt the American railroad’s expansion, is ultimately more apprehensive about damage to running stock than the cost in human lives of his partnership with the Mexicans.

There’s a nod to seminal Sidney Poitier picture The Defiant Ones (1958) with Lyedecker and Joe chained together, and the American, initially disinterested in rebellion, only takes up the cause after a child he has befriended is slaughtered.

100 Rifles shares with The Stalking Moon, The Wild Bunch, Mackenna’s Gold, and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid the theme of relentless pursuit, of an implacable enemy, often with justice or morality or power on their side, who will never give up, and, in a twist on this, in True Grit Rooster Cogburn is the one in fearless pursuit.

At the time, in male-dominated society, the sexual centerpiece was Raquel Welch in various states of undress, forgetting that women, too, were apt to be partial to the sight of an unclothed muscular male. It is Jim Brown who is first seen shirtless. And it is Sarita who takes control of the scene, kissing him as a reward “for all the bad things I said to you.” (Another gender twist, for usually it is the man making reparation.) A more tender scene between Lyedecker and Sarita, ostensibly of the more traditional kind, feisty female transformed into docile housewife by cooking her man a steak invited another reading, more in keeping with her character, not, you may notice, clinging to him, desperate for his love, but happy to enjoy the moment and abandon him when it suits (as Katharine Ross will in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, departing before the outlaws die).

For many, of course, the highlight is Sarita, the leader in all but name, using her body as weapon. As the train approaches the water tower, the soldiers see Sarita standing underneath dressed in only a man’s shirt, taking a shower. The train shudders to a halt for this voyeuristic delight; the camera too, for the audience’s sake, lingering on Sarita’s curves.

Although 100 Rifles is ponderous and improbable in places, with too much emphasis on escape- and-rescue, it certainly achieves its immediate aims, setting up Brown as an action man, giving Welch a role that’s hardly subordinate, ensuring the combination is as sexy as all get-out, while at the same time supplying enough shoot- outs and battle scenes to keep traditionalists happy. As important, director Tom Gries (Will Penny, 1968) is not afraid of using the film to make points, if sometimes a little heavy- handed, about Vietnam and genocide. Clair Huffaker (The Hellfighters, 1968) wrote the screenplay along with Gries based on a Robert MacLeod novel.

All in all, a movie that deserves a good bit more respect.

This review is an edited version of an article that appeared in The Gunslingers of ’69: Western Movies’ Greatest Year (McFarland, 2019) by Brian Hannan (that’s me).