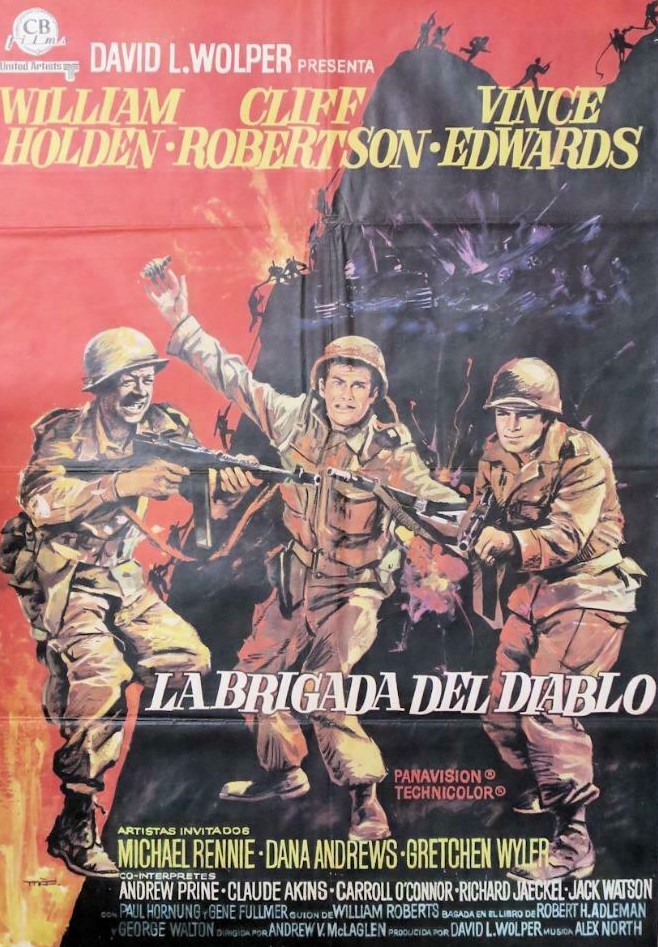

I couldn’t get my head around the idea of the U.S. Army recruiting a bunch of undisciplined misfits, many with jail time, in order to link them up with a crack Canadian outfit. Turns out this part of the film was fictional, the Americans in reality responding to advertisements at Army posts which prioritized men previously employed as forest rangers, game wardens, lumberjacks and the like which made sense since the original mission was mountainous Norway. I should also point out the red beret the soldiers wear is also fictional and while depicted on the poster sporting a moustache commanding officer Lt. Col. Frederick (William Holden) is minus facial hair in the film.

But, basically, it follows a similar formula to The Dirty Dozen (1967), training and internal conflict followed by a dangerous mission. The conflict comes from a clash of cultures between spit-and-polish Canucks and disorderly/juvenile Yanks though, as with the Robert Aldrich epic, the leader taking some of the brunt of the discontent. Collapsible bunk beds, snakes under the sheets and a tendency to fisticuffs are the extent of the antipathy between the units, which is all resolved, as with The Dirty Dozen, when they have to take on people they jointly hate, in this case local bar-room brawlers in Utah.

The movie picks up once they are sent to Italy. Initially employed on reconnaissance, Frederick challenges Major-General Hunter (Carroll O’Connor), who prefers to do things by the book, and in a maverick move sets out to take an Italian position by trekking two miles up a riverbed, creeping into town by stealth and capturing the location without firing a shot.

Next up is the impregnable Monte la Difensa. Taking a leaf out of the Lawrence of Arabia playbook, in a brilliant tactical move, the Americans attack the mountainous stronghold from the rear by way of a mile-high cliff. But that’s the easy part. The rest is trench-by-trench, pillbox-by-pillbox, brutal hand-to-hand fighting.

The battle scenes are excellent and the training section would be perfectly acceptable except for the example of The Dirty Dozen which set a high bar. That said, there is enough going on with the various shenanigans to keep up the interest, but we don’t get to know the characters as intimately as in The Dirty Dozen and there is certainly nobody to match the likes of Telly Savalas, Charles Bronson, Jim Brown and John Cassavetes. That also said, the men do bond sufficiently for some emotional moments during the final battle

At this point William Holden’s career was in disarray, just one leading role (Alvarez Kelly, 1966) and a cameo (Casino Royale, 1967) in four years, and although his screen persona was more charming maverick than disciplined leader he carries off the role well, especially solid when confronting superiors, exhibiting the world-weariness that would a year later in The Wild Bunch put him back on top. Ironically, Cliff Robertson was coming to a peak and would follow his role as the strict disciplinarian Major Crown, the Canadian chief, with an Oscar-winning turn as Charly (1968). Vince Edwards (Hammerhead, 1968) as cigar-chomping hustler Major Bricker makes an ill-advised attempt to steal scenes.

This was the kind of film where the supporting cast were jockeying for a breakout role that would rocket them up the Hollywood food chain – as it did with The Dirty Dozen. Jack Watson (Tobruk, 1967) is the pick among the supporting cast, but he has plenty of competition from Richard Jaeckel (The Dirty Dozen), Claude Akins (Waterhole 3, 1967), Jeremy Slate (The Born Losers, 1967), Andrew Prine (Texas Across the River, 1966), Tom Stern (Angels from Hell, 1968) and Luke Askew (Cool Hand Luke, 1967). Veterans in tow include Dana Andrews (The Satan Bug, 1965) and Michael Rennie (Hotel, 1966).

William Roberts (The Magnificent Seven, 1960) adapted the bestselling book by Robert H. Ableman and George Walton. Director Andrew V. McLaglen (Shenandoah, 1965) was more at home with the western and although there are some fine sequences and the battle scenes are well done this lacks the instinctive touch of some of his other films.

Dirty Dozen-lite.