Excoriating engrossing political drama in which the unscrupulous take the moral high ground and the principled are destroyed. In other words, the reality of power – gaining it and keeping it and all the skullduggery that involves. And it has resonance in today’s cancel culture for it is minor indiscretions from the past that bring down the most upstanding of the species.

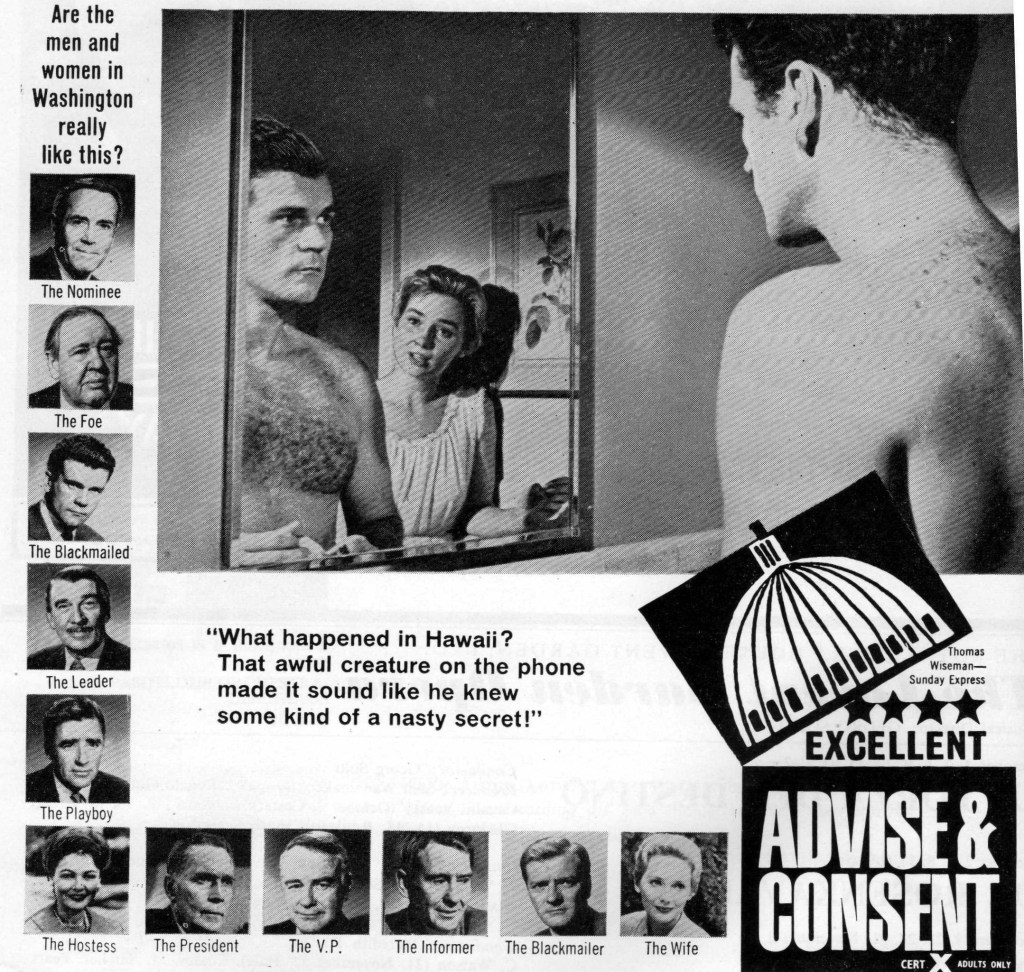

Theoretically, director Otto Preminger (Hurry Sundown, 1967) broke one major taboo in touching on the subject of same-sex relationships. But in reality he took an even bolder step from the Hollywood perspective of giving center stage in the main to older players. Many had first come to the fore in the 1930s or earlier – Walter Pidgeon (Turn Back the Hours, 1928), Lew Ayres (All Quiet on the Western Front, 1930), Charles Laughton (Oscar winner for The Private Life of Henry VIII, 1933) Franchot Tone (Oscar nominated for Mutiny on the Bounty, 1935), Henry Fonda (You Only Live Once, 1937).

This was the kind of all-star cast you used to get in 1960s big-budget pictures filling out supporting roles. But in this ensemble drama, they all, at various times, hold the floor. And this approach lent the movie greater authenticity. Even if few viewers today recognize any, that, too, works in the movie’s favor, giving it an almost documentary feel.

Movies about politics are never heavy on plot, so if you’re looking for a thriller in way of All the President’s Men (1973) go elsewhere. It has more in common with The Trial of the Chicago Seven (2020) with multiple viewpoints and opposing perspectives. What the best movies about politics have in abundance is repartee. Virtually every exchange is a verbal duel, the cut and thrust, the slashing attack, the parry, sometimes the knockout blow delivered through humor.

Given politicians spend most of their lives making speeches, even the shortest of sentences, even the bon mots, have a polished ring. And that, frankly, is the joy of this picture, brilliantly written by Wendell Mayes (Anatomy of a Murder, 1959) from the Allen Drury bestseller. In some respects the plot is almost a MacGuffin, a way into this labyrinthine world, where characters duck and dive like a more elevated breed of gangster

A lesser director would have given in to the temptation of filming these duels in close-up. Instead, Preminger’s direction is almost stately, keeping characters at bay.

A seriously ill President (Franchot Tone), distrusting his feeble Vice-President Harley Hudson (Lew Ayres), decides to fill the vacancy for Secretary of State with highly-principled Senator Robert Leffingwell (Henry Fonda). This not being the beginning of the President’s term, he can’t just do what he wants, his nomination must go before a committee and then face a vote in the Senate.

The Senate Majority Leader Bob Munson (Walter Pidgeon) isn’t too happy with the idea, seeing Leffingwell as a dove, likely to appease the growing Soviet threat. Others on the committee, namely Senator Brigham Anderson (Don Murray) feel the same and the committee hearing has the tone of an interrogation. The fine upstanding Leffingwell parries well until Senator Seabright Cooley (Charles Laughton) introduces a witness Herbert Gelman (Burgess Meredith) who says Leffingwell belonged to a Communist cell, an accusation Leffingwell denies.

Twist number one: Leffingwell has lied on oath. He confesses this to a friend Hardiman Fletcher (Paul McGrath) who then stitches up the witness. The committee apologies to Leffingwell, which means he is a sure thing for the post, but Cooley smells a rat and starts his own investigation. Leffingwell tries to get out of the job but the President won’t allow this. The Majority Leader and Anderson are let in on the secret, the former willing to accommodate the President but the latter outraged and planning to thwart the nomination when it reaches the voting stage at the Senate. Anderson comes under pressure, phone calls to his wife about something that went on in Hawaii.

And so the stage is set. The pressure builds on Anderson. The President becomes more unwell, making the appointment of Leffingwell more crucial. Aware of Anderson’s intentions, the Majority Leader starts whipping up votes, with Cooley doing the same for the opposition. Machinations take over. And for a movie that was initially light on plot, and it ends with three stunning twists, and proving once and for all there is nothing quite so standard as the self-serving politician.

This was the first movie for several years for Henry Fonda (Broadway and television his refuge) and for society hostess Gene Tierney (Laura, 1945) who suffered from mental health problems and the last screen appearance of Charles Laughton. The acting is uniformly excellent and the direction confident and accomplished.

A slow-burner for sure, but a fascinating insight into the less savory aspects of politics and the human collateral damage.