Should have been a classic. The bleakest espionage tale of the decade ends up, unfortunately, in the wrong hands. Betrayal – personal and professional – underlines a sturdy enough narrative of defection, kidnap and rescue, infected with a spread of interesting characters far from the genre cliché.

We open with blonde Russian femme fatale Ludmilla (Moira Redmond), as sleek as they come, killing off her lover once she discovers his true intent. She works for the “Limbo Line,” an organization headed by Oleg (Vladek Sheybal) which whisks Russian defectors back to their home country. In romantic fashion, she inveigles herself into the lives of those who may be, for personal gain, about to take a wrong turn in the service of their country.

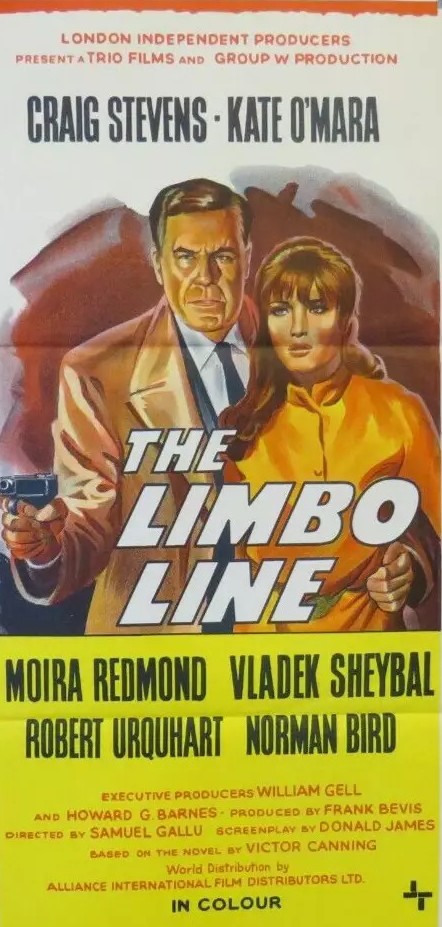

Richard Manston (Craig Stevens), meanwhile, is an operative of an undetermined secret unit, getting cosy with Russian ballerina Irina (Kate O’Mara), a defector, in the hope that she will become the next target for Oleg and thus lead him to his quarry. Responding to his amorous advances, she has no concept of this ulterior motives.

But he’s not the only one in the two-timing racket. Oleg lives high on the hog, a lifestyle financed by holding back remuneration due his operatives, who not only want better paid for the risks they are taking, but draw the line at murder. Ludmilla, meanwhile, uses intimacy with Oleg as a way of keeping tabs on him for her superiors.

Everyone, however, is operating under a new code of restraint. Arms limitation talks between the Superpowers currently taking place mean that neither side wants to be publicly seen to be working in the shadows. Hence, the no-holds-barred methods of both Manston and Oleg are frowned upon. Manston and Ludmilla have more in common than one would normally find in the spy movies of the period, the end justifying the means taking precedence over any personal interest in a lover.

The dangerous romantic elements would have been better dealt with in the hands of a more accomplished director. As it is, Samuel Gallu (Theatre of Death, 1967) has his hands full keeping track of a fast-moving tale as Irina is whisked by boat, bus and petrol tanker to Germany, hidden in such confined spaces the more cautious operatives fear she will die.

Nor, despite his fists, is Manston as good as you would expect from a heroic spy, battered to bits by his opposite number, himself imprisoned in the tanker, becoming a pawn to be sold to the highest bidder.

It’s in the tanker that Irina realizes her lover is deceitful, only using her as bait. Similarly, Oleg doesn’t realize he is every bit as dispensable to the ruthless Ludmilla who wishes to avoid public exposure and is only interesting in taking Irina back to Russia where she will be “re-educated.” Chivers (Norman Bird) looks like the nicer sidekick for Manston, the type to demonstrate fair play, except when he has to drown a suspect in a bath. He has the best line in the film, an ironic one at the climax.

The action, while overly complicated, is well done, none of the over-orchestrated fistfights taking place in odd locations. Chivers has a knack of turning up in the nick of time, but he’s the cleverer of the two.

An actress of greater skill than Kate O’Mara (Corruption, 1968) would have brought greater depth to the betrayed lover, but she does well enough to stay alert during the helter-skelter action. Craig Stevens (Gunn, 1967) was never going to be the right fit for a character required to show considerable remorse at his own actions.

The hard core of political reality, the constant betrayal of both innocent and guilty, the shifting sands of romance sit only on the surface and a better director would have brought them more into the foreground, eliciting better performances for deception incurred in the line of duty at the expense of the personal life.

It’s never a good sign when the bad guys are the more interesting characters and while you might expect Vladek Sheybal (Puppet on a Chain, 1970) to steal the show, he is usurped by Moira Redmond (Nightmare, 1964). A bigger budget would have also offered better reward, but even so Gallu comes up with more interesting camera angles than you might expect. Based on the bestseller by Victor Canning (Masquerade, 1965), he was helped in the screenwriting department by television writer Donald James.

You watch this thinking what might have been.