“Dwarfing the Mightiest! Towering over the Greatest!” wasn’t just the movie’s tagline. It could have easily been used to describe the Pressbook. This folded out into a colossal 40 inches wide by 20 inches high, one of the biggest pressbooks ever produced.

The marketing team produced an impressive list of ideas. Cinema managers were urged to get war correspondents and war heroes involved and to blow up photos of the Victoria Cross. Hanging on the name of the star was a “Baker’s Dozen” competition, inviting people to list the thirteen movies featuring Stanley Baker. Quite how they thought a promotion involving banks would go down is anybody’s guess. Especially as this was the notion: “Zulus are allowed as many wives as they want, provided they can afford to pay for them. The price ranges between six and twenty head of cattle per wife. For an interesting tie-in, get local banks to display money and other barter materials. Give them a montage of still from the picture to display.” Culturally tone-deaf doesn’t cut it.

To attract children there was a coloring-in competition and a school study guide. The movie was available in 70mm Super Technirama so there was a special advertisement linked in to that for cinema going down that route.

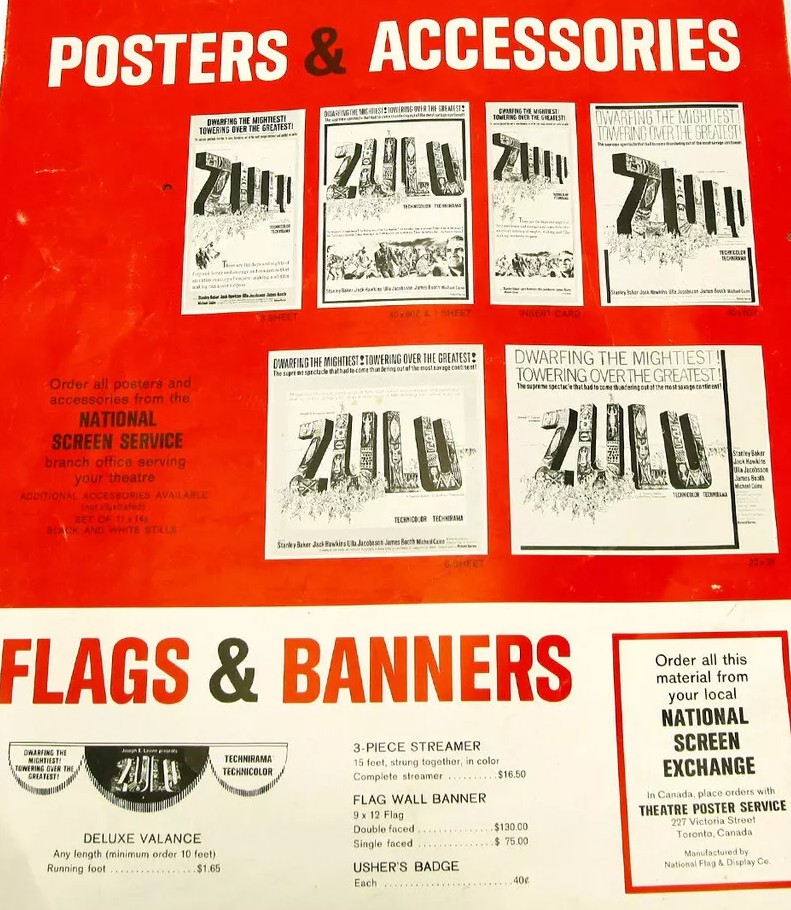

Other taglines included: “The supreme spectacle that had to come thundering out of the most thrilling continent!” and “These are the days and nights of fury and honor and courage and cowardice that an entire century of empire-making and film-making can never surpass!”

And in case hyperbole wasn’t enough, one of the ads spelled out the exciting details. “The Massacre of Isandlwana! The Mating Song of the Zulu Maidens! The Incredible Siege of Ishiwane! Night of the 40,000 Spears! Days That Saved a Continent! Mass Wedding of 2,000 Warriors and 2,000 Virgins! Amid the Battle’s Heat…the Flash of Passion!”

There was a seven-foot high standee and a three-foot 3D illuminated standee.

To help sell the picture to local journalists, little articles were planted that could hook an editor’s interest. For example, when director Cy Endfield glimpsed some soldiers firing their rifles left-handed, he stopped filming, because British soldiers were required to shoot right-handed. The film was shot in the shadows of the Darkensberg Mountains. The river which flowed past Rorke’s Drift was slower than it had been at the time of the battle so the course was altered and dammed to increase the flow. Out of sight of the cameras but essential to filming were the modern villages constructed to house cast and crew, stores, catering and compounds for horses and oxen.

The cast were on set at 6.30am for make-up. The Zulus spent more time in make-up than the British soldiers, as the costume department ensured every aspect of their outfits was historically correct. A total of 100lb of small colored beads was crafted by made by local women for the maidens to wear. A primitive method of making necklaces, strung together with animal sinew and rolled by hand, was employed incorporating a further 100lb of wild syringa seeds which were dyed.

The warrior loincloths of softened animal skins were made the traditional way using stones aqnd animal fat. Shields were also made from animal skin. The teeth of tigers and baboons formed their necklaces. They kept snuff in a small gourd worn round the waist. The purpose of a porcupine quill tucked into their hair was to extract thorns after a long march.

Three cameras were utilized to shoot the blaze that burned down the hospital. “Undress rehearsal” was the name given to the marriage ritual scenes of bare-breasted women.

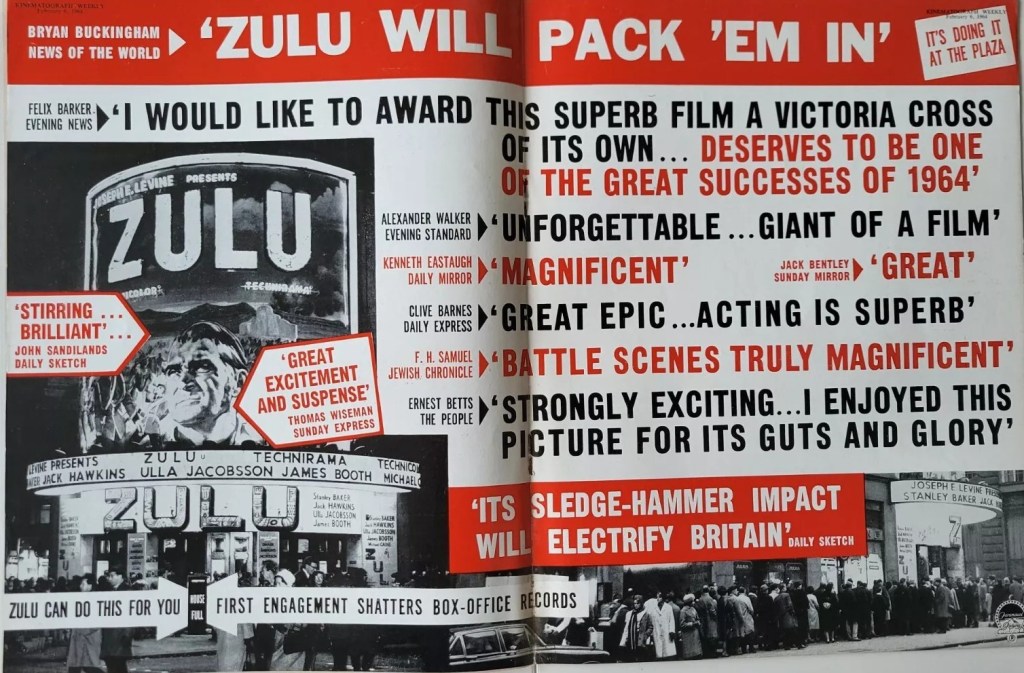

Though Michael Caine was being touted for stardom, as far as the Pressbook was concerned he was relegated to section below Jack Hawkins, James Booth and Ulla Jacobsen who had smaller parts. The movie was a notable change for Jack Hawkins, who saw action in World War Two. Instead of playing his usual hero, he was a weakling and drunk. It was the second English-language film for Swede Jacobsen after Love Is a Ball / All This and Money Too (1963).