Just to follow on yesterday’s reissue of an article of mine regarding the box office of Jaws, I thought it might be timely to ressurect an older article which sets the record straight on some aspects of the movie’s release.

This was in response to the publication of movie critic Richard Schickel’ s Spielberg: A Retrospective which continues to perpetuate the Jaws release myth. I can hardly expect Mr Schickel’s due diligence to cover my own modest tome, In Theaters Everywhere, A History of the Hollywood Wide Release, 1913-2017 (McFarland, 2019), which is now (apparently) the standard text (in case you didn’t know) for all questions relating to wide release, saturation, call it what you will.

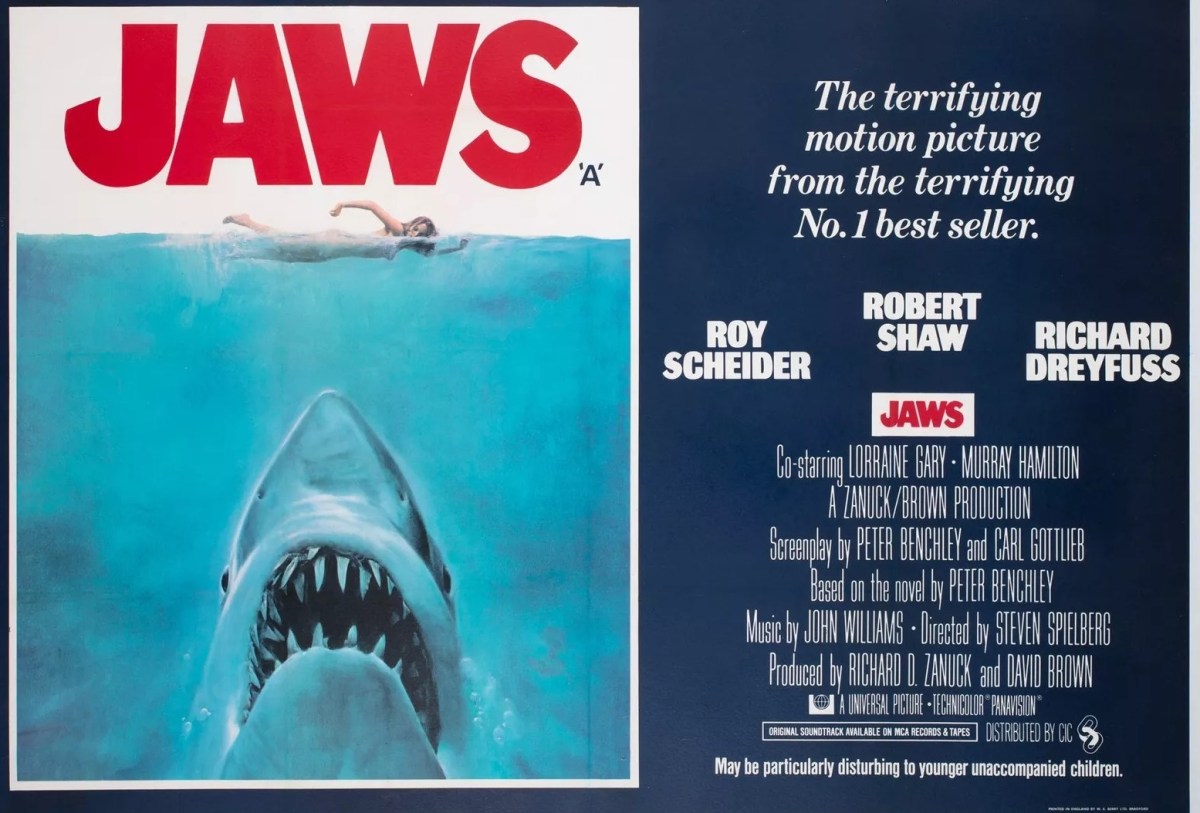

Jaws was not a phenomenon in the normal sense. It did not belong to the realm of the unexplained. In fact, mystery was the least part. It was eminently explainable, despite realms of academics and observers regarding its explosion at the box office in tones of wonder. Hollywood loves a legend, especially one of its own making, and the movie did conform to two attractive narratives, that of the tyro director Steven Spielberg coming good and of the movie overcoming a massive budget over-run (from $3.5 million to $8 million) that could have sunk the enterprise at the outset.

Jaws did not not invent the wide release, summer release or the event movie.

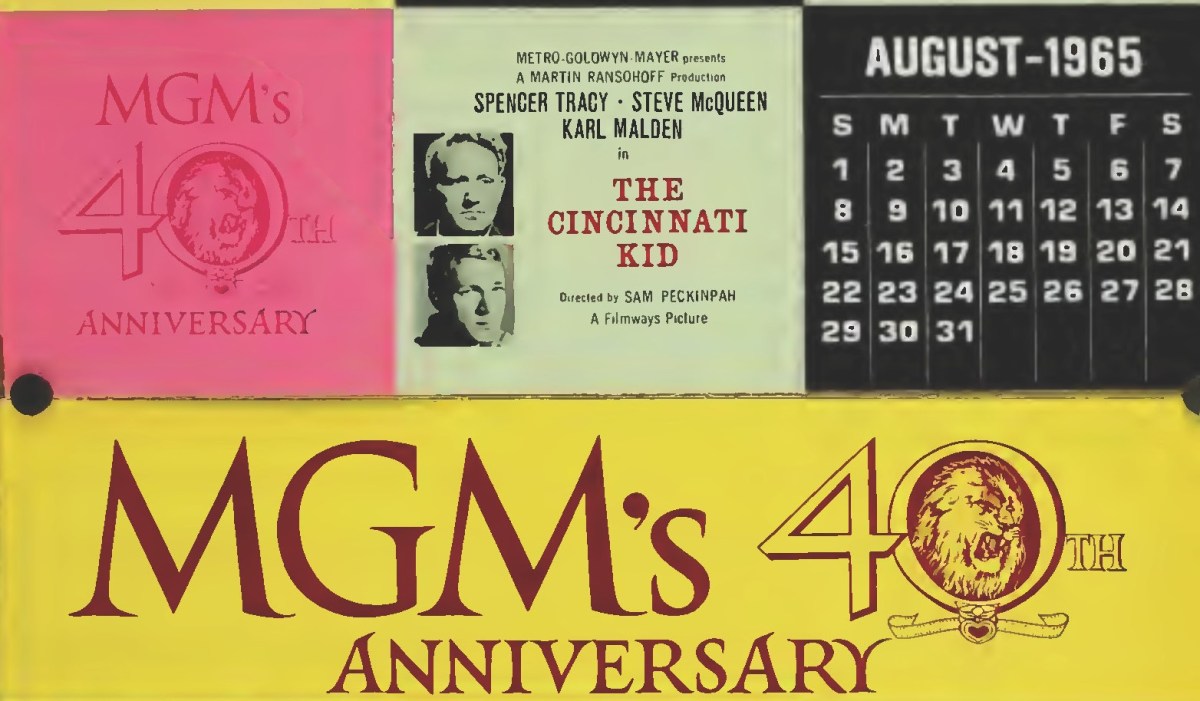

To start with the biggest myth – the wide release – that had been around since the 1930s. The Wizard of Oz (1939) debuted on 400-plus. Warner Brothers signed up 400 for This is the Army in 1943. David O. Selznick created a new phrase for wide release, “blitz exhibitionism,” for Duel in the Sun (1946). In 1948 Twentieth Century Fox opened Iron Curtain, Republic Bill and Coo and Allied Artists The Babe Ruth Story at over 500 cinemas. Fast forward to 1960 and The Magnificent Seven’s initial theater haul was 750. Earlier in 1975, studios had gone for saturation broke with The Master Gunfighter opening on 1,000-plus with Breakout starring Charles Bronson claiming the record of 1,400 houses for the opening week.

In fact, far from inventing saturation or the summer blockbuster or even the event movie, the Steven Spielberg picture, was merely an extension, albeit a wildly successful one, of what had gone before. The problem with the scenario of “Jaws the Legend” is that too few people, academics and journalists alike, placed it against the backdrop of not just the previous few years but the prior decades during which saturation/wide release had flourished.

Long before Jaws came onto the scene, the 1970s had changed and the two conditions that had marked out the previous decade, the reduction in studio output and the increase in saturation, were the prime movers. Jaws was not the beginning of a new era, but very much the opposite, the triumphant culmination of an old one.

It owed a great deal to the other 1970s box office phenomena – Airport, Love Story, The Godfather, Towering Inferno, The Poseidon Adventure and The Exorcist. Their most obvious common thread was that they were based on bestsellers and successful books enjoyed a publicity life and after-life all of their own, as well as providing marketing tie-up benefits and journalistic opportunity.

But turning bestsellers into films was not unusual, Gone with the Wind in 1939 the most obvious example. The top three movies of 1953 – The Robe, From Here to Eternity and Shane – were based on bestsellers as were 1958’s leading trio, Bridge on the River Kwai, Peyton Place and Sayonara. The Guns of Navarone (first in 1961), Spartacus (first in 1962), The Carpetbaggers (first in 1964), Thunderball (first in 1966), The Dirty Dozen (first in 1967), and The Graduate (first in 1968) were all taken from bestsellers. Airport, Love Story, The Godfather and The Poseidon Adventure were the number one films of their respective years, The Exorcist second in its.

The subject matter of The Godfather and The Exorcist attracted a mass of newspaper headlines, Love Story because it was such an unexpected hit, while Jaws afforded endless journalistic opportunity. The Godfather, The Exorcist and Jaws all had in common budget and shooting problems. Like Jaws, the theme tunes to Love Story, The Godfather and The Exorcist were million-sellers. Airport apart, none of the biggies boasted established stars, Marlon Brando, although a giant of the 1950s, no longer a box office attraction while Gene Hackman was a potential one-hit wonder prior to The Poseidon Adventure. Ryan O’Neal and Ali McGraw (Love Story), James Caan and Al Pacino (The Godfather), Ellen Burstyn (The Exorcist) and Roy Scheider and Richard Dreyfuss (Jaws) were virtually unknowns.

The idea that summer was a release desert had not been true for more than a decade, Paramount launching ‘a powerhouse of important product’ – a total of eight pictures – in 1970 – Norwood had 1,400 bookings between May 27 and July 8 in four waves of 450 theaters – more, incidentally, than the number of theaters showing Jaws in its opening week – each running the picture for two weeks. In 1973 Twentieth Century Fox, MGM and Columbia opened a total of 19 movies during the season.

The Twentieth Century Fox schedule comprised the long-awaited reissue of The Sound of Music, Robert Aldrich’s The Emperor of the North, Battle for the Planet of the Apes (the fifth in the series), Jeff Bridges as The Last American Hero (with a tie-up with over 16,000 gas stations) based on articles by Tom Wolfe, and The Legend of Hell House, the whole shebang kicked off in late June by a featurettes on ABC and an eight-day television campaign.

Columbia reckoned it would need a company record 3,150 prints to meet demand for George C. Scott and Faye Dunaway in Oklahoma Crude, Burt Reynolds as Shamus, Charles Bronson in The Valachi Papers, romantic comedy Forty Carats, remake Lost Horizon, and concert documentaries Let the Good Times Roll and Wattstax.

The MGM septet included Yul Brynner in Westworld, Burt Reynolds in The Man Who Loved Cat Dancing and Shaft in Africa. In 1974, Twentieth Century Fox targeted summer with ten movies including Richard Lester period romp The Three Musketeers, heist drama 11 Harrowhouse, chase picture Dirty Mary Crazy Larry, Spys, and the ‘Ape-athon’, a quintuple bill of all the Planet of the Apes pictures, plus another outing for The Sound of Music. Substantial radio advertising was added to usual television/newspaper marketing mix, with stations in 30 key cities running an eight-week campaign.

The studio cleared $35 million over 13 weeks, up $5 million on its previous best summer in 1970. Paramount’s high voltage program included The Longest Yard and Chinatown. But it was not just the majors who recognized the importance of summer, Crown International and American International both reported record business for summer 1974.

The $1.8 million Universal spent marketing Jaws was both a large and modest amount. In proportion to production costs, it was less than Joe Levine devoted to Hercules or to the promotional budgets for four-wallers, and a lot less, than was allocated The Culpepper Cattle Company or Breakout. That television accounted for 38percent was not astonishing either since research proved that newspaper advertising was more effective.

Although claiming to be the largest amount spent in television spot advertising, compressed into the three days prior to opening and opening day (June 20) itself, it was rather last-minute compared to the selling of The Man with the Golden Gun for which United Artists ran 700 prints of a teaser trailer in theaters six months prior to launch and 30-second advertisements on the ten top-rated television shows well in advance of opening.

The tactic of specifying which television slots of movie would advertise on, as Jaws did, was far from rare, four-wallers specializing in this, and Breakout had done the same. In fact, the record that Universal claimed for Jaws, too, was questionable since Breakout had 42 30-second spots compared to 23 for Jaws. Disney, overall, spent a lot more. Nor did Universal knowingly aim for a summer launch – only shooting delays prevented it opening at Xmas 1974. Nor did publisher and studio jointly adopt the same visual for Jaws from the start – a March 1974 trade advertisement in Box Office differed substantially from the iconic poster.

The marketing device of reporting grosses week-by-week was not novel either. Most the big hitters of the 1960s did not pull in money at top speed. Love Story changed all that. Paramount kept the industry and the wider newspaper planet up-to-date on a weekly basis of the movie’s unprecedented progress. Its $2.46million (actually $2.36million) in three days from 165 was the biggest in history and it set the seal on the industry reporting the weekend rather than weekly gross. The second weekend was $2.49million, the third $2.4million, the fourth $2million and the fifth $2.3million. That the second and third weekends both out-grossed the first, and the fifth weekend out-grossed the fourth, were publicity bonuses. The first five weeks topped $17.5million. Four weeks later, theater count risen to 231, it totaled $28.4million and two weeks further on, on 282 theaters, the gross stood at $35.4million.

When in 1972 The Godfather so quickly gunned down Love Story, it set in motion an ongoing marketing story, and the question facing each new hit, from The Poseidon Adventure to The Exorcist and The Sting, was box office speed and whether it could topple the reigning champion.

By 1975 accelerated grossing had become common: The Trial of Billy Jack hoisted $9 million in five days, The Man with the Golden Gun $5.1 million in a week, The Sting $7 million in two weeks, Papillon $11.25 million in three weeks, Airport ’75 $10 million in a month, Earthquake $7.3 million in a month, The Godfather Part II $22.1 million in under five weeks, Magnum Force $18 million in five weeks.

So when Jaws showed the potential to reach the very top, Paramount raced out of the traps with a series of advertisements showing the gap closing between the new movie and the title holder. This tack in itself was nothing new – The Robe, hoping to catch up on Gone with the Wind, had made a big hullabaloo of reporting opening week’s grosses day-by-day in the trade press and Twentieth Century Fox had capitalized on The Sound of Music’s overhauling of Gone with the Wind.

Jaws simply took advantage of a media ready-and-waiting for an accelerated box office story. Since money was made faster than ever before, box office records fell faster than ever before. It made news precisely because it was sustainable – week after week – an ‘immediate stampede’ at the box office – $14.3 million ($34,900 per theater average) in the first week, $33.8 million in two weeks and three days, $69.7 million in five weeks and three days, $100 million in eight weeks and three days, $150 million in twenty-three weeks. (It did not venture overseas until November, first stop Australia, and then it was a major Xmas release in seven hundred theaters in forty-four countries.)

Substantial questions remain about the Jaws saturation. Although history proved the Universal strategy to be a success, I am not convinced it was as deliberate as suggested nor that Universal had any idea of the winner it had on its hands.

There had been much larger saturations going back two decades and both Trial of Billy Jack in 1974 and Breakout in 1975 had debuted in over 1,000. The number of theaters involved in the Jaws launch was, I shall argue, proof of the studio’s lack of confidence not the opposite.

Studios with what they believed were guaranteed winners had consistently used a different scenario. The Exorcist opened in 24 theaters, Earthquake in 62, Papillon in 109 and The Godfather Part II in 157. Movies that opened in the Jaws range and above – Magnum Force in 418, The Man with the Golden Gun in 635, The Trial of Billy Jack, Breakout and The Master Gunfighter in 1,000-plus – were not expected to last as long. Statistics proved that for features with high box office expectation the slower limited roll-out was the more effective approach. The question really to be asked is whether Universal realistically expected Jaws to bring in rentals in the region of The Exorcist ($66million), The Sting ($68million) and The Godfather Part II ($128.9million) or whether its expectations were more in the Magnum Force ($18.3million) ballpark. I would argue that circumstantial evidence pointed to the latter. No other studio would throw away a prospective gold-plated opportunity on a saturation of the Magnum Force variety unless it reckoned grosses around the Dirty Harry sequel mark would count as a good return on its investment.

I would also challenge whether Universal actually deliberately limited the number of original theater participants. I would suggest it is much more likely that the studio encountered considerable resistance from exhibitors to being asked to hand over 90percent of the gross, agree a 12-week run and contribute to the national television campaign for a movie with an unknown director and no stars. Also, the movie did not, like The Exorcist or The Godfather, open in engagements exclusive to one city, but went multiple from the start, 46 in New York, 25 in Los Angeles; even Airport 1975 only opened in five theaters in New York.

More likely, I would venture, is that the original theater count declined over the blind-bidding controversy and/or when Universal and exhibitors reached a negotiating impasse. Negativity could also have been sparked by the recent experience of Breakout which fell short of box office targets. It certainly strikes of wisdom-after-the-event for Universal to claim this was a deliberate strategy. Nobody spends $1.8million on launch advertising in the hope that it would carry the picture all through summer since that would suggest a paltry $225,000 per week over an eight-week season.

Universal spent nearly two-fifths of the film’s production budget on that kind of launch because they wanted big opening grosses. For the first month, Jaws was restricted to 409 theaters in the U.S., the number increasing to 700 after five weeks and then to 900 after another three weeks, suggesting that exclusivity was part of the deal for initial exhibitors.

A tougher business take on the limited opening was that Universal shot itself in the foot.

With an 800-theater launch, grosses would have been stratospheric, even higher than the movie actually achieved. Ironically, it was roadshow precedent and practice that created the opportunity for Jaws to break all box office records. Without the guaranteed run that roadshows traditionally enjoyed, theaters would have dumped the movie, regardless of grosses, because they were already committed to another feature. Longevity, not opening week grosses, was the key to the Jaws record-breaking.

So if it was not a unique development in saturation that precipitated the Jaws success, or a new way of latching onto summer as an unrealized opportunity, or a breakthrough in publishing or record sales, or a novel approach to television advertising, to what else can you ascribe the movie’s unprecedented success?

Well, the answer is the simplest, the oldest, of all. The public just liked it. It hit a chord the way a raft of movies as different as Gone with the Wind, The Sound of Music and The Godfather before it. And it also benefitted from the public reappraisal of reissues, the idea that you could go back to see a movie you enjoyed again and again. Jaws broke no saturation rules and did not set new saturation boundaries. All the hard work on that had already been done. But it certainly reaped the reward.

SOURCE: Brian Hannan, In Theaters Everywhere, A History of the Hollywood Wide Release, 1913-2017 (McFarland, 2019) p192-195.