For the first four decades of the Hollywood business, success in markets other than domestic was random. Many countries restricted the number of U.S. films that could be shown, others like Britain prevented American studios for a long time taking out of the country money earned at the box office. There was always the chance it could be less profitable if a dominant foreign cinema chain or distributor demanded a larger slice of the box office. In addition, some genres that worked in America stiffed abroad – musicals and comedies found it hard to translate.

Except in extremely sporadic fashion, foreign box office was not reported in the trade media until the 1990s. So there was no such thing as worldwide grosses available on any real scale. These days for many films overseas receipts bring in more than domestic – Zootropolis a current example with around 70 per cent of takings coming from abroad – but that was virtually never the case until the arrival of the James Bond pictures, which acquired a genuine global brand, in the 1960s.

However, the United Artists archives held by the University of Wisconsin provide some fascinating insights into the growing power of the foreign box office in the 1950s. Movies released into the foreign market would make a percentage of their domestic take. But that varied enormously. Even the star-studded Around the World in 80 Days (1956), the second-biggest blockbuster of the year Stateside, with a colossal $16 million in domestic rentals took in less than a quarter of that abroad, just $3.9 million.

For some films, the percentage was better. Controversial William Holden drama The Moon Is Blue (1953) notched up $1.3 million abroad compared to $3.5 million at home. War picture Beachhead (1954) starring Tony Curtis bundled up $1 million overseas as against $1.4 million in domestic. The Barefoot Contessa (1954), boasting Humphrey Bogart and Ava Gardner, added $2.2 million in foreign coin to its domestic tally of $3.25 million.

Richard Burton as Alexander the Great proved the breakthrough, domestic’s $2.5 million matched by the exact same amount abroad. Robert Mitchum in Foreign Intrigue (1956) went one further, reversing the usual situation, foreign of $1.14 million ahead of domestic’s $1 million.

But the UA star with the biggest consistent pull overseas was Burt Lancaster. Robert Aldrich’s Apache (1954) knocked up $1.75 million abroad compared to $3.25 million at home. Vera Cruz, (1954) also directed by Aldrich and coupling Lancaster with Gary Cooper, hit a home run – the $3.94 million abroad being just short of the $4.5 million at home. The actor’s first venture into directing The Kentuckian (1955) kept up the pace with $1.97 million overseas versus $2.6 million at home.

While these were all action pictures, it was acrobatic drama Trapeze (1956), with Lancaster and Tony Curtis fighting over Italian sex symbol Gina Lollobrigida, that made Hollywood wake up. In the U.S, it came third on the annual box office charts with $7.5 million in rentals. If that took the industry by surprise that was nothing compared to foreign where the movie racked up $7.4 million.

Lancaster remained potent. Submarine war picture Run Silent, Run Deep (1958), co-starring Clark Gable, did virtually as well abroad as at home – $2.42 million overseas compared to $2.5 million at home.

Perhaps learning from the experience of Trapeze, UA went for broke with historical actioner The Vikings (1958) starring Kirk Douglas and Tony Curtis. Domestic of $7 million, enough for fifth place in the annual box office league, was beaten by an overseas count of $7.34 million.

For the first time it appeared that Hollywood could count on overseas to swell the box office in sizeable fashion, thus allowing studios to invest more, especially in historical movies with an action angle, thus opening the door for the spate of 1960s roadshows. Such results also cemented star salaries. If a Burt Lancaster picture could make the same again abroad as at home that put him in a new category of dependable stars and allowed studios to gamble on increasing his salary.

That Charlie Chaplin proved a better draw overseas than in the U.S. was largely by default. The actor-producer-director had fallen foul of American politics with the result that his latest release Limelight (1952) flopped. Abroad it was a different story and Limelight hit a tremendous $5.1 million. With the U.S. reissue market also showing resistance to Chaplin oldies, it was left to overseas audiences to show what cinemas were missing as Modern Times (1936) racked up $2.1 million and The Gold Rush (1925) $1.25 million. For comparison the reissue of Red River (1948) pulled in just $19,000 overseas.

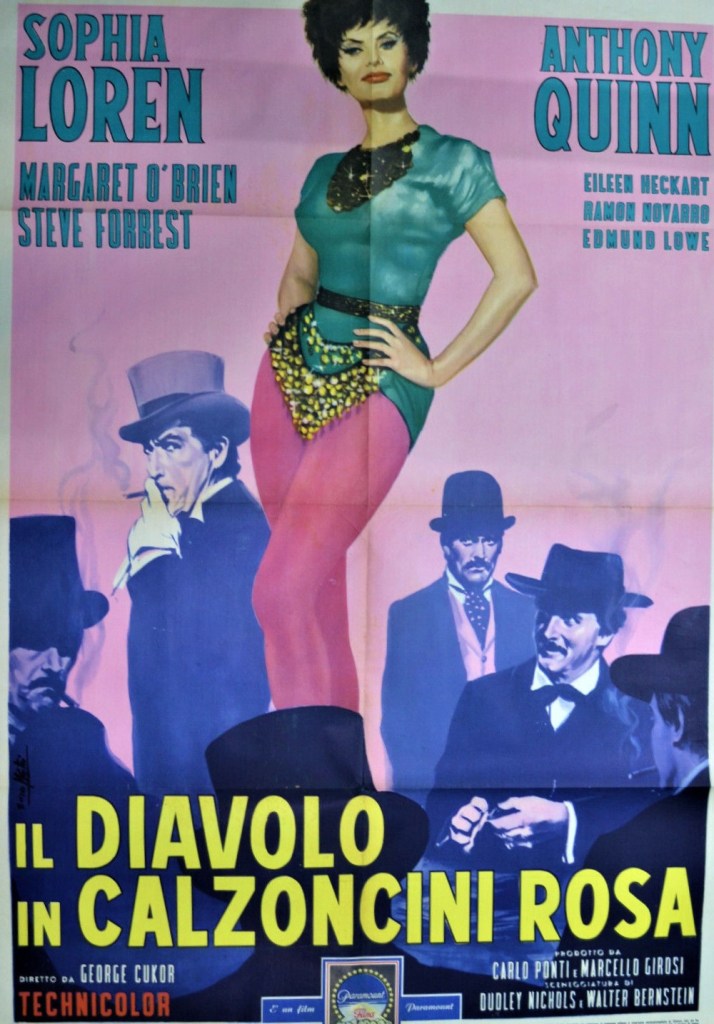

Other notable leaders in the overseas market included: Frank Sinatra, Cary Grant and Sophia Loren in The Pride and the Passion (1957) with $3.17 million ($5.9 million domestic); Billy Wilder’s Agatha Christie adaptation Witness for the Prosecution starring Tyrone Power and Marlene Dietrich on $2.81 million ($3.75 million domestic); and Love in the Afternoon (1957) with $2.7 million ($2 million domestic) starring Gary Cooper and Audrey Hepburn.

Also making a noise overseas were: Stanley Kramer medical drama Not As a Stranger (1955) toplining Olivia De Havilland, Frank Sinatra and Robert Mitchum on a $2 million haul ($7.1 million domestic): Sinatra again in Otto Preminger’s study of addiction The Man with the Golden Arm (1953) on $1.87 million ($4.35 million domestic); Sinatra in war picture Kings Go Forth (1958) on $1.83 million ($2.8 million domestic) and Kirk Douglas as The Indian Fighter (1955) with $1.84 million ($2.45 million domestic).

Bob Hope went against the grain when his overseas tally for Paris Holiday (1958) at $1.8 million bested the $1.5 million of domestic while John Wayne and Sophia Loren’s foreign engagements for Legend of the Lot (1957) counted as a disappointment with just $1.66 million compared to $2.2million domestic.

Low-budget Oscar-winner Marty (1955), produced by Burt Lancaster’s company, was as big a surprise abroad as at home, sprinting to $1.43 million ($2 million domestic). Others worth noting included: Bandido! starring Robert Mitchum on $1.42 million overseas ($1.65 million domestic); David Lean’s romantic drama Summertime (1955) with Katharine Hepburn on $1.3 million ($2 million domestic); Anthony Mann’s Korean War venture Men in War (1957) on $1.26 million ($1.5 million domestic); and Clark Gable in The King and Four Queens (1956) hauling in $1.24 million ($2.5 million domestic).

Olivia De Havilland as The Ambassador’s Daughter (1956) tabbed $1.1 million overseas ($1.5 million domestic) and Gary Cooper in Mark Robson’s Return to Paradise (1953) tallied $1.1 million ($1.8 million domestic). Slow burners numbered Dale Robertson in Sitting Bull (1954) with $1.1 million ($1.5 million domestic) and Stanley Kubrick’s anti-war picture Paths of Glory (1957) with Kirk Douglas shooting up $1 million ($1.2 million domestic).

SOURCE: “Foreign Distribution Gross Estimates,” United Artists Archives, Box 1, Folder 8, University of Wisconsin. Note that in this case “gross” means “gross rentals” not “box office gross.”