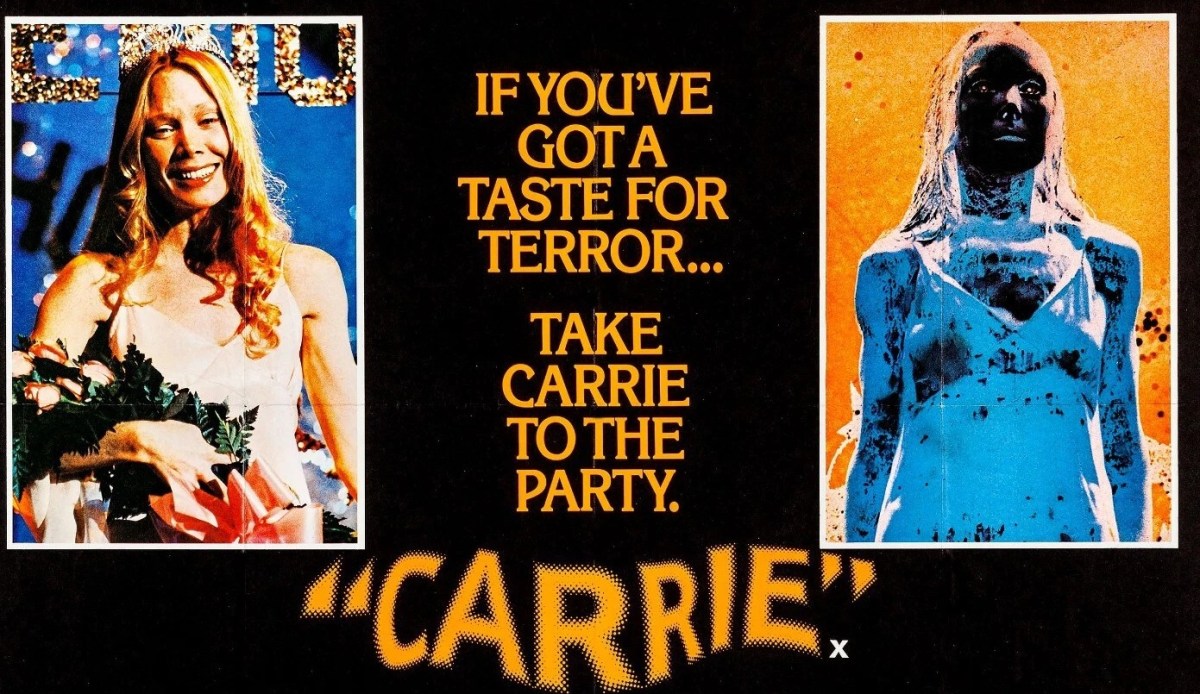

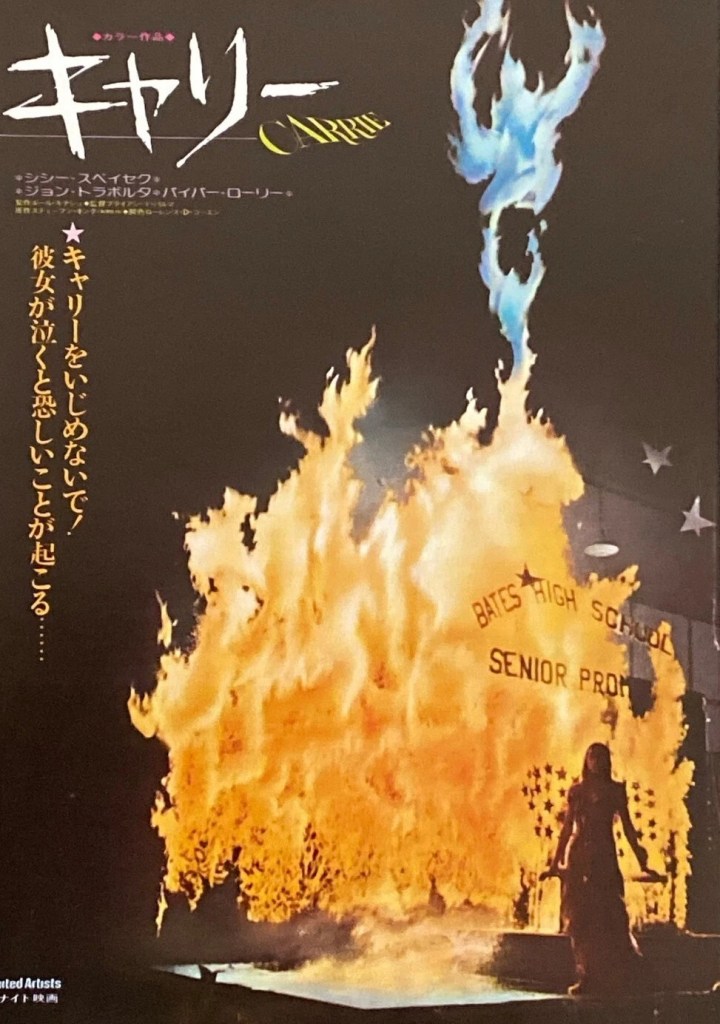

Could have easily gone so badly wrong. You got Mean Girls vs Teen Romance. Demented Mother of Elmer Gantry vs Demented Daughter of Psycho. Why did nobody ever think before that slow-mo that used to be the preserve of lovers gambolling in fields and cowboys being bloodily gunned down could be as easily employed to watch naked girls in the shower. Throw in split-screen and a couple of other technical devices. And the shock ending which triggered a new cycle.

There’s a heck of lot of face-slapping that wouldn’t pass muster today and not exclusively male either, hard-ass teacher Miss Collins (Betty Buckley) setting about venal pupil Chris (Nancy Allen), Chris giving as good as she gets from boyfriend Billy (John Travolta). And if you were a rising star like John Travolta you might think twice about the effect on your career of battering a pig to death with a sledgehammer. Try those capers now and you’d run into the woke police.

But it’s surprisingly feminist. Women twist their men round their little finger, the headmaster does the bidding of Miss Collins, All-American Boy Tommy (William Katt), decked out in a super perm, accedes to the barmy request of his girlfriend Sue (Amy Irving), attempting to assuage her guilt over her role in bullying Carrie (Sissy Spacek), to give up her place at the Senior Prom to the nerd, and Chris has no problem getting Billy to go along with her scheme for humiliating vengeance.

In another movie, Carrie, an eternal victim, would have been the Final Girl but such is her wrath nobody’s left standing to qualify for that position. Nobody escapes, innocent and guilty alike, put to the sword. There’s sex in all its disguises, ranging from a virgin’s first tender kiss to a blowjob to sin to rampant voyeurism.

That it works so well is in part due to the malevolence of all concerned, the above mentioned whacking, the mother locking the child in a closet, the gleeful girls tormenting Carrie, and Carrie spiteful in her blood-soaked vengeance. The telekinesis on which the tale depends is cleverly introduced, a few minor incidents hinting at this unnatural power, Carrie herself doing the research rather than consulting a specialist and weighting the picture down with turgid exposition.

The neat running time – barely topping 90 minutes – eliminates any slack. And director Brian De Palma (The Untouchables, 1987) has sufficient command of the tension and occasional moments of bravura that it’s touched on the ironic climax before you realize quite where it’s going. Atmospheric score by Pino Donaggio (Don’t Look Now, 1973) guides us along, the haunting melody that wouldn’t be out of place as a love theme lets us know there’s more to the shower scene than we might expect while the sharp chords accompanying the slaughter reminiscent of Psycho (1960).

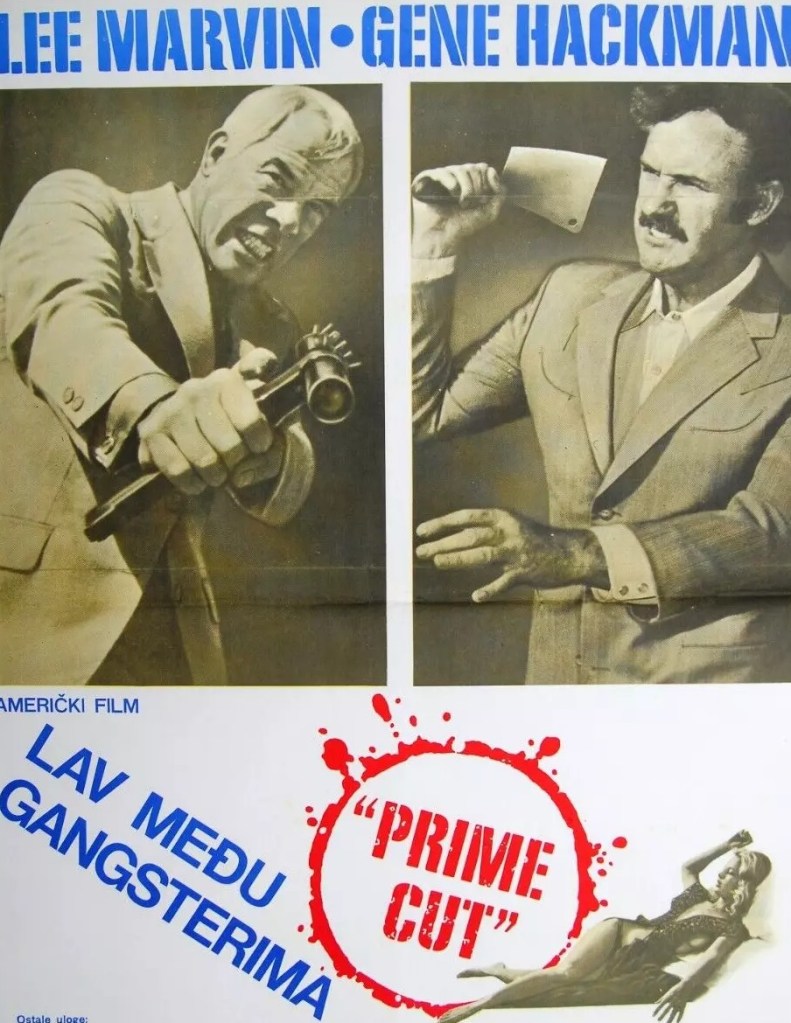

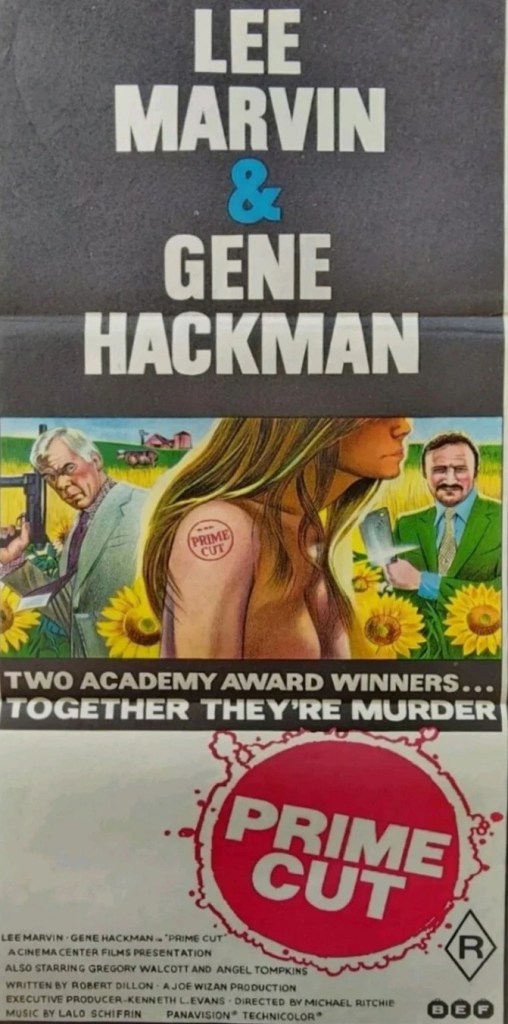

Announced to the world Stephen King as writer of immensely cinematic books, and made De Palma a commercial name. Sissy Space (Prime Cut, 1972) and Piper Laurie (The Hustler, 1961) were nominated for Oscars and the movie served as launch pad for several of the cast, most notably John Travolta (Saturday Night Fever, 1977), including Nancy Allen (Dressed to Kill, 1980), William Katt (Big Wednesday, 1978) and Amy Irving (Micky + Maude, 1984). Written by Lawrence D. Cohen (Ghost Story, 1981).

Still a terrific watch.