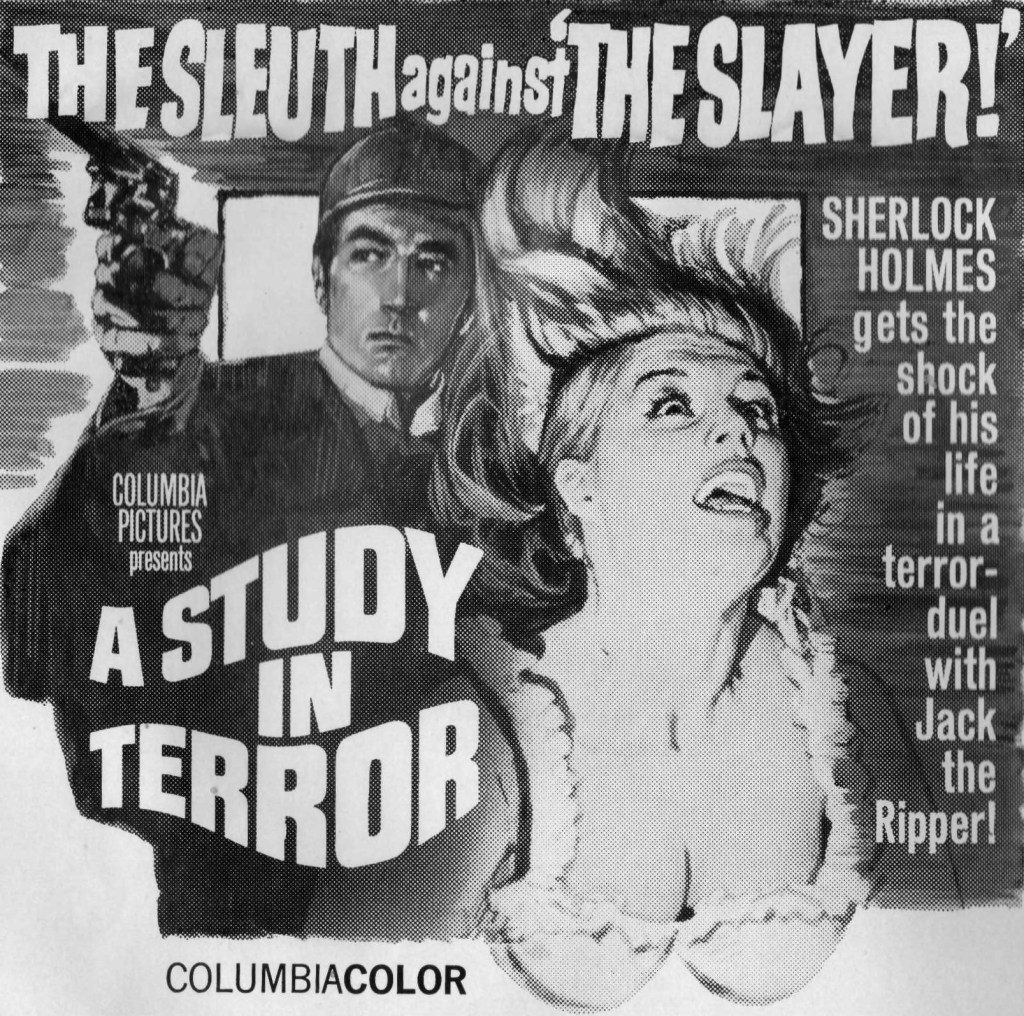

Although Billy Wilder had written a script based on The Life of Sherlock Holmes, he was not considered as its director. Mirisch was looking at a budget in the region of $2 million, which would rule out any big star. However, there were issues with the Conan Doyle Estate which was in the process of firing up other movies based on Sherlock Holmes, A Study in Terror (1965) being the most recent. That had been the brainchild of Henry Lester and perhaps to general astonishment these days Mirisch had agreed Lester would be allowed to make more Sherlock Holmes pictures as long as they remained very low-budget, on the assumption, presumably, that the marketplace would treat them as programmers rather than genuine competition.

However, Mirisch and UA retained the upper hand as regards the Conan Doyle Estate and “could cut him (Lester) off at such time as we have made definite plans to proceed.”

There was another proviso to the deal. The Estate would agree to forbid any further television productions unless Mirisch decided it wished to go down the small screen route itself. It was odd that Mirisch had eased Billy Wilder out of the frame given the mini-major had enjoyed considerable success with the director on Some Like it Hot (1959) and The Apartment (1960), a commercial partnership that would extend to The Fortune Cookie (1966).

Instead, Mirisch lined up British director Bryan Forbes who would be contracted to write a screenplay based on the Wilder idea. The sum offered – $10,000 – was considered too low, but it was intended as enticement, to bring Forbes into the frame as director. If Forbes refused to bite, “the only other name suggested and agreed upon was that of John Schlesinger.” Although David Lean was mooted, UA were not in favour. Mirisch didn’t want to risk paying for a screenplay before there was a director in position.

The offer of the Sherlock Holmes picture was seen as a sop to Forbes. At this meeting, Mirisch had canned The Egyptologists, a project which Forbes believed had been greenlit. And why would he not when he was being paid $100,000 for the screenplay. In bringing the project to an untimely close Mirisch hoped to limit its financial exposure to two-thirds of that fee. Should Forbes balk at Sherlock Holmes, he was to be offered The Mutiny of Madame Yes, whose initial budget was set at $1.5 million, plus half a million for star Shirley Maclaine. Another Eady Plan project, this was aimed to go before the cameras the following year. If Forbes declined, then Mirisch would try Norman Jewison with Clive Donner and Guy Hamilton counted as “additional possibilities.”

As for Billy Wilder he had much bigger fish to fry. He was seeking a budget of $7.5 million to adapt into a film the Franz Lehar play The Count of Luxembourg to pair Walter Matthau and Brigitte Bardot. Should Matthau pass, Wilder would try for Cary Grant (whose retirement had not yet been announced) or Rex Harrison. Both sides played negotiation hardball. UA currently in the hole for $21 million for The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965) and Mirisch, having pumped $13 million into the yet-to-be-release Hawaii (1966), didn’t want to commit to another unwieldy expensive project. So Mirisch insisted the project advance on a “step basis” allowing UA to reject the project after seeing the screenplay. Wilder countered by insisting that if it went into turnaround he, rather than the studio, would have the right to hawk it elsewhere (generally, studios tried to recover their costs if a movie was picked up by another studio). But Wilder was also in placatory mood and even if UA rejected this idea he was willing to work with the studio on a Julie Andrews project called My Sister and I.

However, UA and Mirisch were all show. “After Billy left the meeting,” read the minutes, “it was agreed we would not proceed with The Count of Luxembourg since we did not want to give Billy the right to take it elsewhere if United Artists did not agree to proceed.” Harold Mirisch was detailed to give Billy the bad news, but use a different excuse.

Mirisch was also on the brink of severing links with Blake Edwards. Negotiations for a new multiple-picture deal were to be terminated, which would mean the director would only earn his previous fee of $225,000 for What Did You Do in the War Daddy? It was also sayonara for Hollywood agent Irving Swifty Lazar, whose current deal was not working out to the studio’s satisfaction.

Other long-term deals with directors were under discussion. While its previous John Sturges movie, The Hallelujah Trail (1965), had flopped, UA was still keen on the Mirisches pursuing a long-term deal with the director, feeling that he was a “good picture-maker with the right project.” To that end, it was suggested Mirisch reactivate Tombstone’s Epitaph, but emphasising Stuges had to bring the cost down.

At this point nobody knew Norman Jewison was embarking on all almighty box office roll – The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming set to hit the screens, In the Heat of the Night at screenplay stage, so Mirisch was prescient in trying to put together a long-term deal with the director. Wind on Fire and Garden of Cucumbers were seen as tentpoles for a multi-picture deal. Mirisch had already agreed a $50,000 producer’s fee for Wind of Fire, payment of one-third of which was triggered for supervising the screenplay.

The meeting also gave the greenlight to Death, Where Is Thy Sting-A-Ling, a project that would be later mired in controversy with shooting ultimately abandoned. The go-ahead was given with the proviso the Mirisches secured the services of Gregory Peck or an actor of his stature. Budget, excepting Peck’s fee, was just over $3 million and it was another one hoping to take advantage of the Eady Plan.

This kind of production meeting was probably more typical than you would imagine, studios trying to keep talent sweet while not committing themselves to dodgy product. It’s perhaps salutary to note that of the projects under discussion, only a handful found their way onto cinema screens. Garden of Cucumbers (as Fitzwilly), How To Succeed in Business, having met budget restraints, and Tombstone’s Epitaph (as Hour of the Gun) with James Garner all surfaced in 1967 and Inspector Clouseau the following year. Neither of the Steve McQueen projects survived nor the pair proposed by Billy Wilder. High Citadel, Saddle and Ride, The Narrow Sea, The Great Japanese Train Robbery, and The Cruel Eagle failed to materialize. Billy Wilder eventually made The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes under the Mirisch auspices but not until 1970.