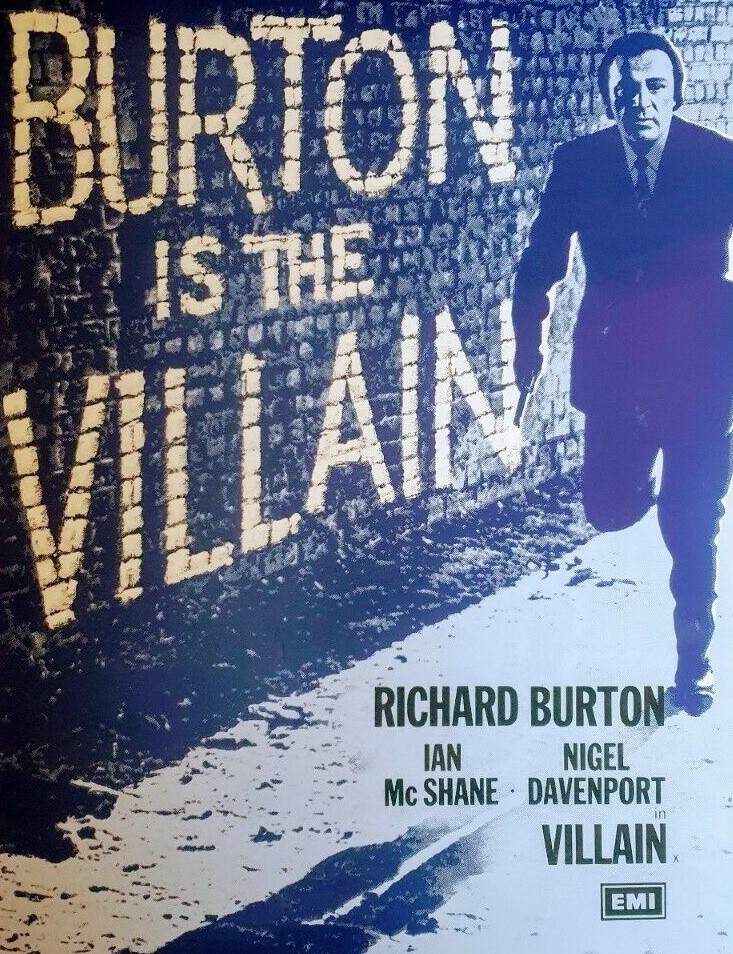

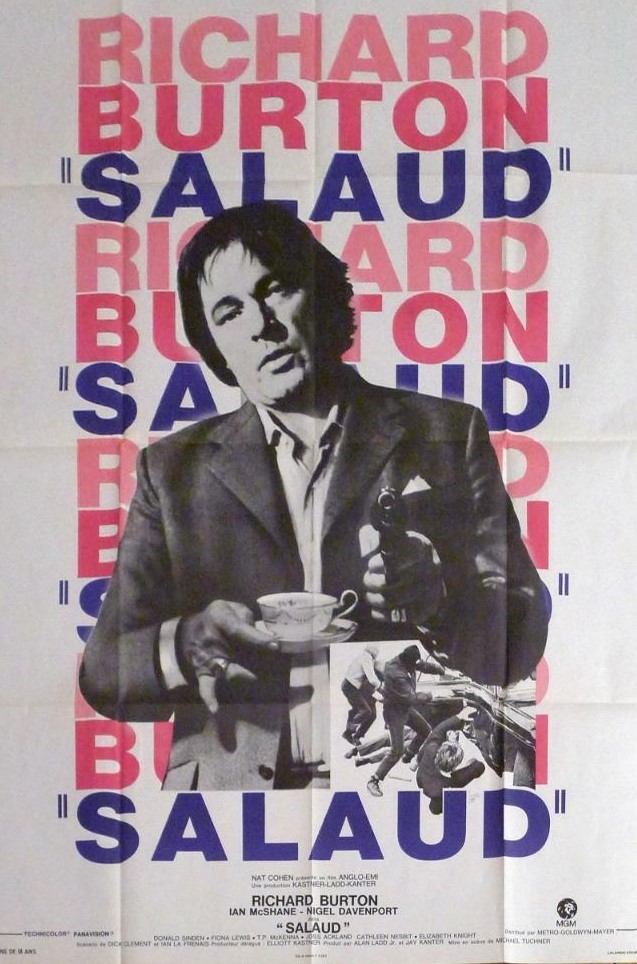

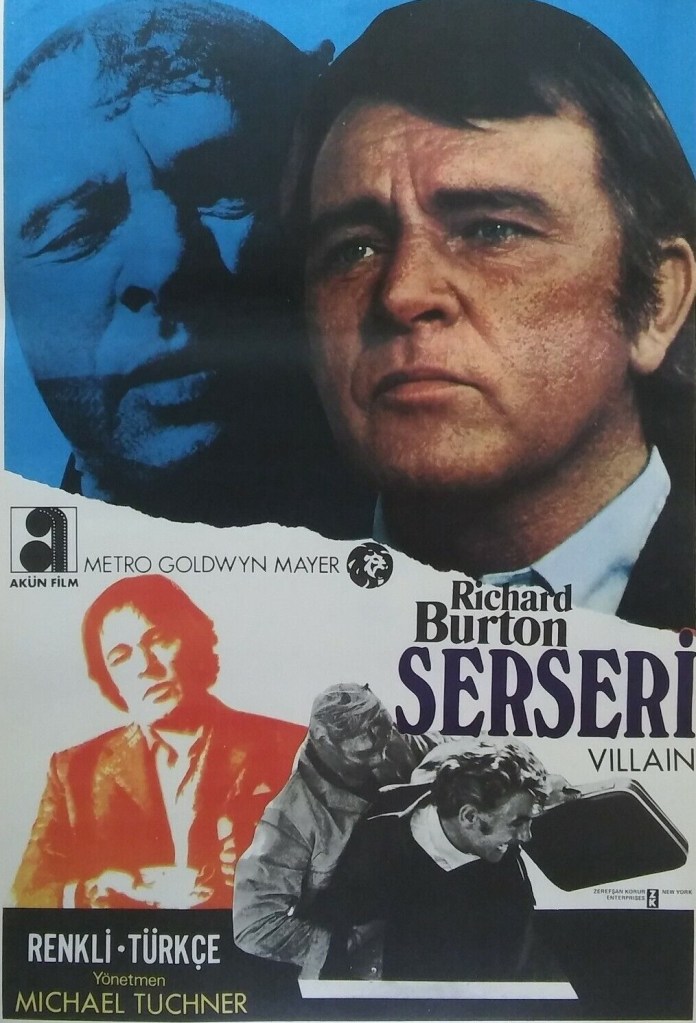

Get Carter, out the same year, tends to get the critical nod over Villain, but I beg to differ. Not only do we have the most realistic robbery yet depicted on screen, but Richard Burton (Becket, 1964), delivering one of his greatest performances, is nearly matched by Ian McShane, flexing acting muscles that would come to fruition in Deadwood (2004-2006) and John Wick: Chapter 4 (2023), and Nigel Davenport’s cop, as cool under pressure as Frank Bullitt.

Where Michael Caine in Get Carter is primarily the avenging angel, Burton’s Vic Dakin is every bit as complex as Michael Corleone. Way ahead of its time in portraying Dakin as a gay gangster in sympathetic fashion, he also has a moral code akin to that of Don Corleone. While the Mafia chieftain drew the line at selling drugs, Dakin despises MP Draycott (Donald Sinden) for his corruption and views with contempt sometime boyfriend Wolfe (Ian McShane) for small-time drugs and girl peddling.

He reveres (as did Don Corleone) family values, bringing his aging mother tea in bed, kissing her affectionately on the forehead, treating her to a day out at the Brighton. But he also rejoices in violence as much as any of Scorsese’s gallery of thugs.

Complexity is the order of the day. Every dominant character, whether operating on the legal or illegal side of the street, receives a come-uppance verging on humiliation. Dakin himself is arrested in full view of his mother. The bisexual Wolfe, who otherwise dances unscathed through the mire, is beaten up by Dakin and humiliated when his male lover shows his female lover, the upmarket Venetia (Fiona Lewis), the door. Top gangster Frank (T.P. McKenna), who attempts to lord it over Dakin, ends up whimpering in agony in the back seat of a car.

Maverick cop Mathews (Nigel Davenport) is brought to heel by internal politics and frustrated at home when his wife is indifferent to the late night shenanigans of his son. Even cocky thug Duncan (Tony Selby), with a quip to terrify victims, is reduced to a quivering wreck under the relentless stare of Dakin.

Unlike The Godfather, mothers excepted, wives and girlfriends are complicit. Little chance of a shred of feminism here. Women are chattels, Venetia is traded out as a “favor” to Draycott, terrified gangster’s moll Patti (Elizabeth Knight) also used in that capacity by Wolfe. Draycott professes little interest in whether the women, procured in this fashion, enjoy sex with him.

So, to the story. Tempted by a tasty payroll robbery, Dakin steps out of his usual line of work, a protection racket, and joins up with two other leading hoods, Frank (T.P. McKenna) and his brother-in-law, the belching Edgar (Joss Ackland). But the robbery goes wrong. The tail is spotted by the payroll car and the victims almost evade capture. But stopping the payroll car renders the getaway vehicle virtually useless, a flat tyre soon flies off and they drive for miles on a wheel rim.

The payroll is well-guarded and several of the villains emerge badly scathed. Worse, the cases containing the cash have anti-theft devices, equipped with legs that spring out and red clouds of smoke. And there are ample witnesses. Edgar is quickly apprehended, and the movie enters a vicious endgame.

Contemporary audiences were put off by the obvious references to the Kray Twins and the Profumo Affair and American audiences had long shown an aversion to Cockneys (though that is not so apparent here) and critics gave it a mauling, the general feeling being that after Performance (1970) and Get Carter, the British public was entitled to the more genial criminal as exemplified by The Italian Job (1969), incidentally another U.S. flop.

There are many superb moments: Dakin’s affectionate stroke of Wolfe’s shoulder, Dakin and his sidekick’s nonchalant stroll over a footbridge as they make their escape, Dakin pushing Draycott into a urinal, Wolfe abandoning Venetia at a country house party so that Draycott can avail himself of the “favor,” Dakin’s love for his mother. Throwaways point to deeper issues, a country stricken by strikes and political corruption.

Dakin, unaware he has made a target for his own back by the unnecessary brutal treatment of an associate, comes up against a cool implacable cop, as confident as Dakin without the arrogance or recourse to brutality, easy with the quip.

A modern audience might appreciate the violence more than the acting, given that a la Scorsese we are supposed to revel in criminal behavior, but it’s the performances that lift the film. Burton had entered a career trough, sacked from Laughter in the Dark (1969), involved in a quartet of financial and critical turkeys – Boom! (1968), Candy (1968), Staircase (1969) and Raid on Rommel (1971) – with only another Oscar nomination for Anne of the Thousand Days (1970) to alleviate the gathering gloom that would see him strike out in his next nine pictures before another nomination for Equus (1977) restored some stability.

So this is a superb character, suited and booted he might be, doting on his mother, but underneath stung by insecurity and unable to rein in his sadistic streak. A marvellous addition to the canon of great gangster portrayals.

Ian McShane, too, provides a performance of great depth, in his element when skirting around the small-time world, out of his depth with the big time, the charm that can hook a vulnerable upper-class lass like Venetia as likely to attract a malevolent mobster, the former under his thumb, the latter controlling. To see him go from cheeky chappie with a winning grin to penitent lover forced to dismiss Venetia is quite an achievement.

Nigel Davenport (Sands of the Kalahari, 1965) is on top form and the supporting cast could hardly have been better – T.P. McKenna (Young Cassidy, 1965), plummy-voiced Donald Sinden (Father, Dear Father TV series, 1969-1972) playing against type, Joss Ackland (Rasputin: The Mad Monk, 1966). Throw in a bit of over-acting from Colin Welland (Kes, 1969) plus Fiona Lewis (Where’s Jack?, 1969) at her most accomplished.

Michael Tuchner (Fear Is the Key, 1972) directs with some style from a screenplay by Dick Clement and Ian La Fresnais (Hannibal Brooks, 1969) working from the novel by al Lettieri.

Ripe for reassessment.