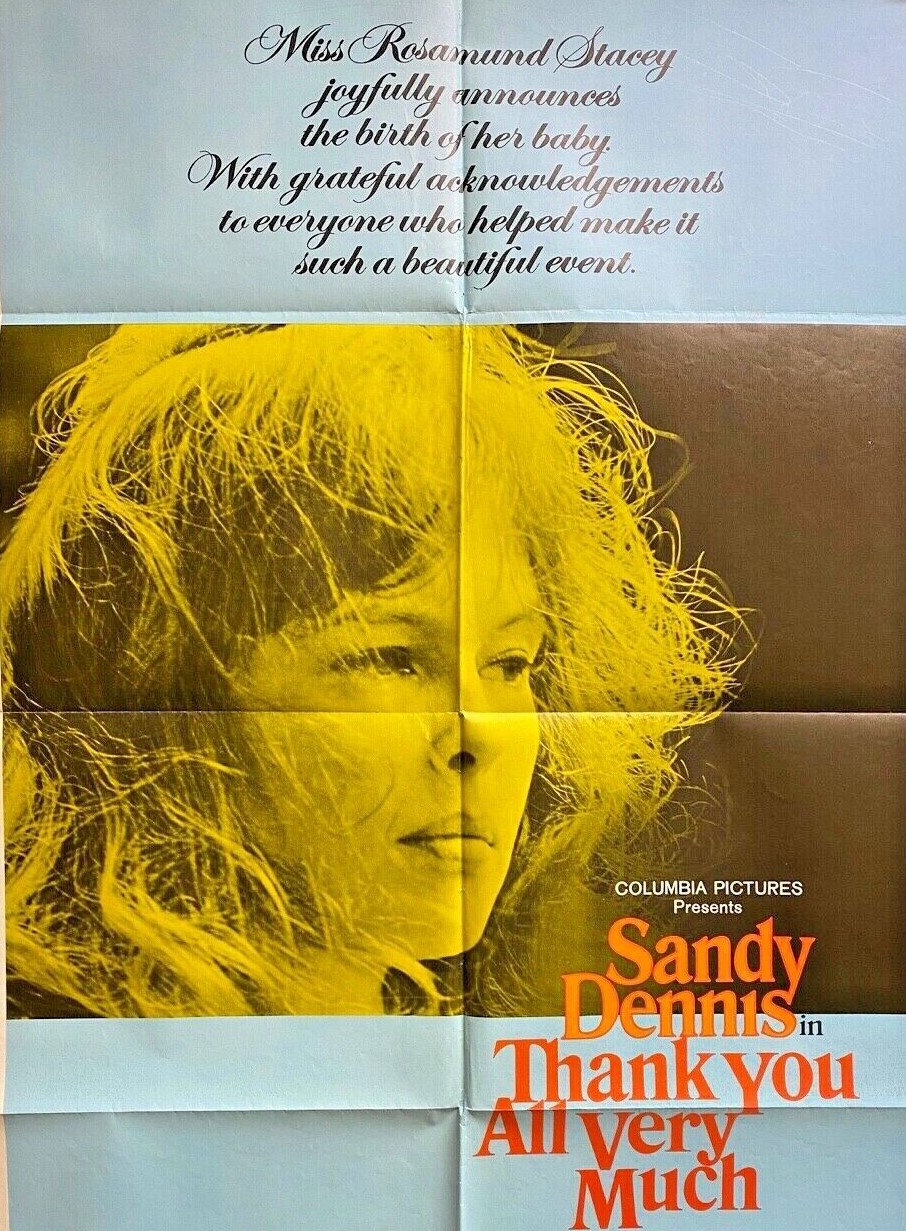

The combination of Amicus and pregnancy might lead audiences to expect a monster baby of It’s Alive (1974) dimensions. Nor would you associate the studio, which made its name in horror pictures where women were either victims or sex objects, with feminism. But producer Milton Subotsky plays it straight, the only concession to the Margaret Drabble source novel is to change the title, from the obvious The Millstone to the more ironic Thank You All Very Much (in the U.S.) and A Touch of Love (in the U.K.).

It doesn’t go down the single mum kitchen sink route either, abandoned female struggling in poverty and desperate for a man. In fact, except in one instance, dependable men are in short supply. Though, it has to be said, female support isn’t much better.

by low-budget actioner aimed at men.

Pregnant after a one-night stand with television personality George (Ian McKellen), post graduate student Rosamund (Sandy Dennis), after toying with home-made efforts at abortion, decides to have her baby. Luckily, she can afford it, living in a splendid apartment in what looks like South Kensington rather than a bedsit in a more squalid area of London. Her parents are more remote, tending towards the upper rather than the middle classes, the type who park their offspring in boarding school to minimize a child’s impact on their busy social lives.

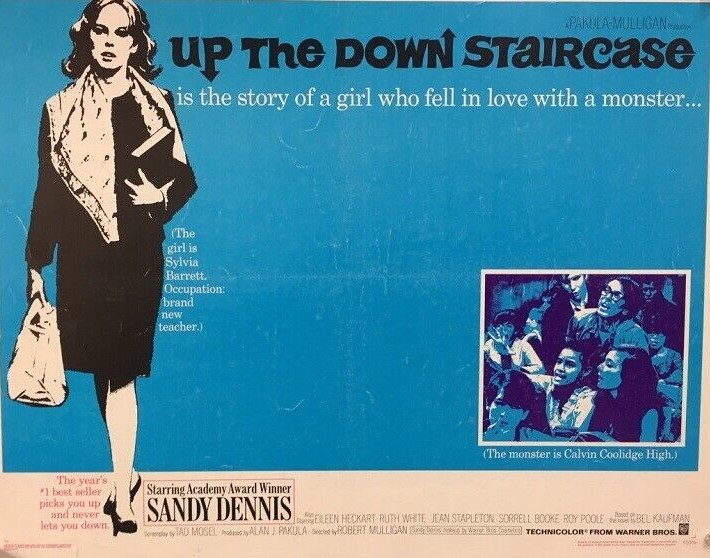

Sandy Dennis (Up the Down Staircase, 1967) has quite a trick in her screen persona. She is generally initially presented as weak, whiny, vulnerable, trademark quavering voice helping this along, a potential victim until her inner steel exerts itself and you realize she is not the person you think she is. Almost an actorly version of the Christopher Nolan trope of letting you believe a character is one type of person until he/she turns out to be another.

There isn’t too much of the mother being tormented out of her skull by a baby screaming its head off – or as in Nolan’s latest opus Oppenheimer, a mother unable to cope handing the child over to someone else to look after – but she is very much alone, unable to reveal to the father his part in the pregnancy, despite having another one-night stand with him. So mostly it’s her coping with the system, suffering in silence in the traditional British manner endless bureaucracy, sitting in a long queue in a waiting room, and being beset by the very people you might expect to be more sympathetic.

But the nurses seem very much cut from the same pragmatic cloth as her parents. Prior to birth, one nurse informs her that it’s selfish not to give the child up for adoption. When the baby is convalescing in hospital after a heart operation, matron (Rachel Kempson), a graduate from the Nurse Ratchet school of health care, consistently refuses to let the mother see the baby as it’s apparently against hospital rules until in the best scene in the movie, and the one that achieves the Dennis trick, she literally screams the place down.

That nurses on a maternity ward full of little more than I would imagine at times screaming children are so disturbed by the prospect of an adult rebelling against the stiff upper lip conventions of British society says a great deal about the kind of uniformity and subservience expected of the public by those in charge of any large organization. None of the Angry Young Men of earlier in the decade would dream of such a simple solution to a problem.

Eventually, being allowed to sit by her child’s bedside until late into the night permits Rosamund to complete her thesis and win her PhD. She’s not quite as hard-nosed about George as she likes to imagine but since he’s not sufficiently taken with her child to allow it to disrupt a projected trip abroad, she realizes what had been plainly obvious to the audience that she is better off without men – or at least this particular, ineffective, individual – for the time being.

So most of the film is about Rosamund learning to enjoy her independence, able to achieve her goals without male assistance, and that’s generally done by action rather than dialogue or monologue, some heated debate or major crisis. Excepting the incident with Nurse Ratchet, it’s just about coping, and awareness that maternity need not cramp ambition.

Her arty friends (and parents for that matter) are all too keen on having a good time – the males mostly trying to bed her – to lend much support. Some like Lydia (Eleanor Bron) have a warped view of life.

In his movie debut Waris Hussein (The Possession of Joel Delaney, 1972) takes the striking narrative route of not allowing the picture to become tangled up with romantic complication, keeping it squarely focused on feminism, succeeding on your own terms, not reliant on men, embracing both motherhood and career. Margaret Drabble wrote the screenplay.

Sandy Dennis (Up the Down Staircase, 1967) delivers another telling performance, one of the few actresses permitted to be center stage in a non-romantic narrative, because this is the kind of role she can easily pull off. She manages a convincing British accent without falling prey to too much Britishness.

Minus the tell-tale diction that marked his later career, Ian McKellen (Alfred the Great, 1969) has an effective debut as the charming though selfish lover. Eleanor Bron (Two for the Road, 1967) is the pick of the supporting cast as the soft-hearted best friend who is too pragmatic by half. Others popping up include John Standing (Walk, Don’t Run, 1966), Margaret Tyzack (2001: A Space Odyssey, 1968), Maurice Denham (Midas Run, 1969) with Rachel Kempson (The Charge of the Light Brigade, 1968).

Unfussy direction matched with another brilliant turn by Sandy Dennis makes this a must-watch.