Miracle this was made at all with so many neophyte producers involved. First up were Kenn Donellen and Jacqueline Babbin. No Hollywood experience. He was the television rep for Ford Motors, she worked for David Susskind’s talent agency. But like everyone else in the business in the early 1960s, when major studios were on the point of collapse, they thought they could do better. Especially after they nabbed the property, Life with Mother Superior by Jane Trahey, from under the noses of Disney and Universal.

The pair picked it up pre-publication, three months before it was launched by Farrar Strauss in September 1962 after serialization in McCall’s magazine and turned into a speedy bestseller. They got preference because they struck the kind of deal with the author that only newcomers desperate to get into the business would make. As well as paying a hefty fee upfront they guaranteed the author a percentage, plus, unheard-of for a first-time writer, a “say-so on production.” That clause alone would have alarmed any other studio.

Donellen and Babbin were prepared to put up half the $750,000 budget if the remainder was met by a major studio or independent. Production was scheduled for Spring 1963.

Not surprisingly, it suffered from lack of partners. Briefly, it shifted to the bulging portfolio of Ross Hunter. He envisaged an all-star cast older cast in the style of Disney’s Pollyanna (1960): Barbara Stanwyck (The Night Walker, 1964), Loretta Young (whose last movie It Happens Every Thursday was in 1953) and Jane Wyman (Pollyanna) as nuns, which removed the onus from youngsters Patty Duke (The Miracle Worker, 1962) and Mary Badham (To Kill a Mockingbird, 1962). Interestingly, his production of The Chalk Garden (1964) with Hayley Mills was so successful in its New York run it earned back its negative cost.

But that didn’t float Universal’s boat and Columbia stepped in in 1964, handing the production to another neophyte, William Frye. He belonged to a new breed of producers who had cut their teeth in television as writers before moving into overseeing small-screen programs, and attempting the jump to features. Frye had been more successful than most. He had a production deal with Columbia.

But initial attempts to film Guardians from the novel by Helen Tucker, Grass Lovers, thriller Linda by John D. MacDonald and Lie Down in Darkness by William Styron to be directed by John Frankenheimer came to nothing. In the end, Columbia handed him Mother Superior, as the movie was now known.

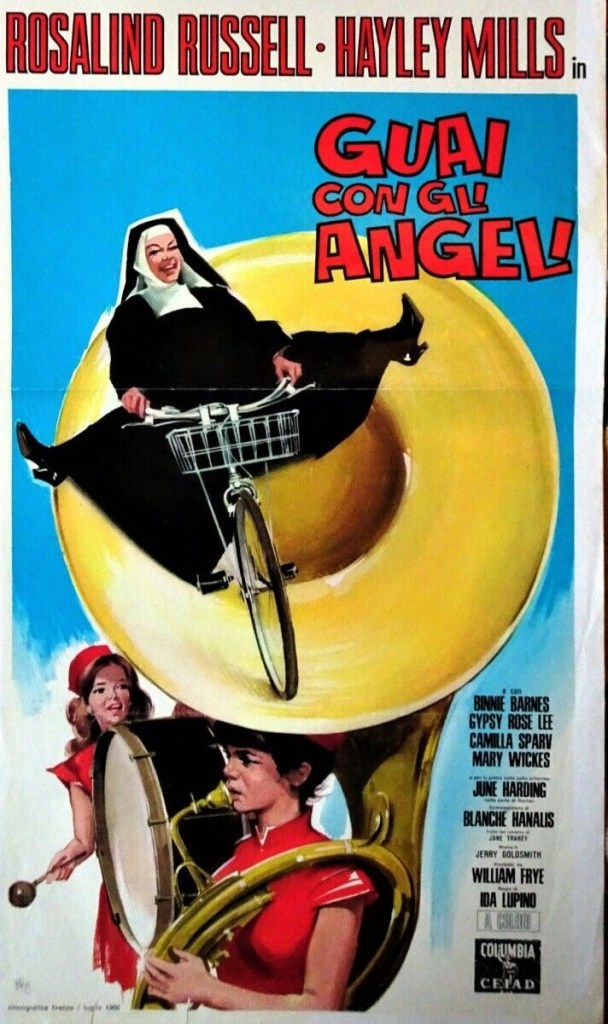

But this was his first production and either through naiveté, ambition or publicity-seeking genius, Frye had the sensational idea of fielding a million-dollar offer to Greta Garbo to play Mother Superior, in what would have been the comeback to end all comebacks, given she had not made a movie in three decades. That would have made a heck of a dent in a movie budgeted at $2 million. Needless to say, the offer was declined. Eventually, he settled on four-time Oscar nominee Rosalind Russell, for whom this was also something of a comeback, her first picture since Gypsy (1962).

Hayley Mills had parted company with Walt Disney after a run of six films that had turned her into the biggest child star (admittedly, a small pool) in the world. But she was trying to break out from that persona. She was 19 and couldn’t keep playing kids forever. In an attempt to spread her wings, she and her father, actor John Mills (Tunes of Glory, 1960) set up production outfit The Company of Six along with fellow actors Richard Attenborough, Herbert Lom and Curt Jurgens and writer-director Bryan Forbes.

And she faced another dilemma. Her Disney pictures were big box office, but other movies made out-with that brand were less successful. In some respects, this was an ideal halfway house. In this picture she wasn’t saddled with being a tomboy and there was no romance and she was able to infuse the role with more emotional maturity while still developing her comedy chops.

It wasn’t her only choice. She was set for Deep Freeze Girls along with Nancy Kwan and Sue Lyon for Seven Arts. Production was scheduled to begin in October 1965, following on from The Trouble with Angels, but it never got off the ground.

As importantly, Mills fitted the new Columbia talent development strategy. The studio had signed up seven young stars but aimed to have 40-50 on board within a year, partly as a way to reduce costs and partly as a method of courting the younger audience. So, you couldn’t have a better poster girl for that particular scheme than Hayley Mills.

By this point, Ida Lupino, once a big movie star (High Sierra, 1940) and an accomplished director after a string of B-film thrillers in the early 1950s such as Outrage (1950) – one of the first X-certificate films in Britain – and The Bigamist (1953), was now a television gun for hire, reduced to directing episodes of Bewitched, The Twilight Zone, Dr Kildare and The Fugitive. But she had worked for Frye in television when he was in charge of the General Electric Theater and Thriller series Still, it was a brave move to hire a director, never mind a female director, who had been out of the movies for 13 years.

In Hollywood, Lupino was now in a majority of one, the only female director working in the mainstream. Up till then, in the whole of the decade, only two other women had found a directing gig and that was in the independent sector, Shirley Clarke with The Connection (1961) and Joleen Compton with Stranded (1965), though that had been shot in Greece. Although Variety ran a front-page splash in 1964 entitled “Women Directors Multiply,” the situation overseas was little better. Belgian Agnes Varda (Cleo from 5 to 7, 1962), Swede Mai Zetterling (Loving Couples, 1964) and Lina Wertmuller (Lizards, 1963) were the only examples the trade magazine could find.

It was Lupino’s decision to limit the use of color, mainlining on “stark black and white and charcoal grey.” When color did appear it was in a “sudden splash” such as a swimming pool or a green meadow or the red of the marching band outfits. “The possibilities of color are fantastic,” opined Lupino.

Columbia was on such a production spree, 77 pictures on its slate, space so tight on its sound stages, that some scenes on The Trouble with Angels were farmed out to Goldwyn Studios. Most of the train scenes were shot at the Santa Fe depot, though the opening train sequence took place at Merion train station in Pennsylvania.

The movie title was changed to The Trouble with Angels due to a surfeit of movies about nuns. Of course, nuns had periodically hit pay dirt at the box office. Look to Heaven Knows Mr Allison (1958) and The Nun’s Story (1959). But their box office had hardly prepared anyone for The Sound of Music (1965). And coming up on the outside was The Singing Nun (1966) starring Debbie Reynolds, though a foreign effort La Religieuse (1965) had been banned in France.

Lupino’s picture and The Singing Nun were soon on collision course, vying to become the Easter 1966 attraction at the prestigious Radio City Music Hall in New York (the largest auditorium in the country with over 6,000 seats). The Trouble with Angels lost out and settled for the first run Victoria and the arthouse Beekman (not such an unusual mix as, due to a dearth of screens thanks to roadshow long-runners, arthouses were often drafted in to make up the numbers).

William Frye planned to team up again with Mills and The Trouble with Angels screenwriter Blanche Hanalis for When I Grow Rich, a $3 million romantic drama to be filmed in Turkey for Columbia, but that fell through and after falling in love with her director Roy Boulting on The Family Way (1966), Mills career headed in another direction.

The Trouble with Angels was so successful it spawned a sequel, Where Angels Go Trouble Follows! (1968). Mills spurned an offer to reprise her role. Rosalind Russell returned, her young nemesis played by Stella Stevens (Sol Madrid/The Heroin Gang, 1968).

SOURCES: “Young Producers Not Arty At All,” Variety, June 20, 1962, p4; “Frye Buys Grass Lovers,” Variety, September 12, 1962, p11; “Sanford and Frye of TV To Make Theatrical Films,” Box Office, January 7, 1963, p10; “Col-Frye TV Pact,” Box Office, August 19, 1963, p10; “Women Directors Multiply,” Variety, March 11, 1964, p1; “Columbia Policy,” Variety, May 6, 1964, p13; “Ida Lupino To Direct Col’s Mother Superior,” Variety, February 10, 1965, p15; “Seven Arts Pix Multiply,” Variety, March 31, 1965, p4; “Form Company of Six,” Variety, April 21, 1965, p28; “Ross Hunter’s Crowded Future,” Variety, May 12, 1965, p7; “Production Spills Over,” Variety, September 15, 1965, p22; “One Nun or Another for Music Hall,” Variety, January 12, 1966, p17; Robert B. Frederick, “Sister Act,” Variety, April 20, 1966, p22; “Istanbul Rides Location Boom,” Variety, May 4, 1966, p150.