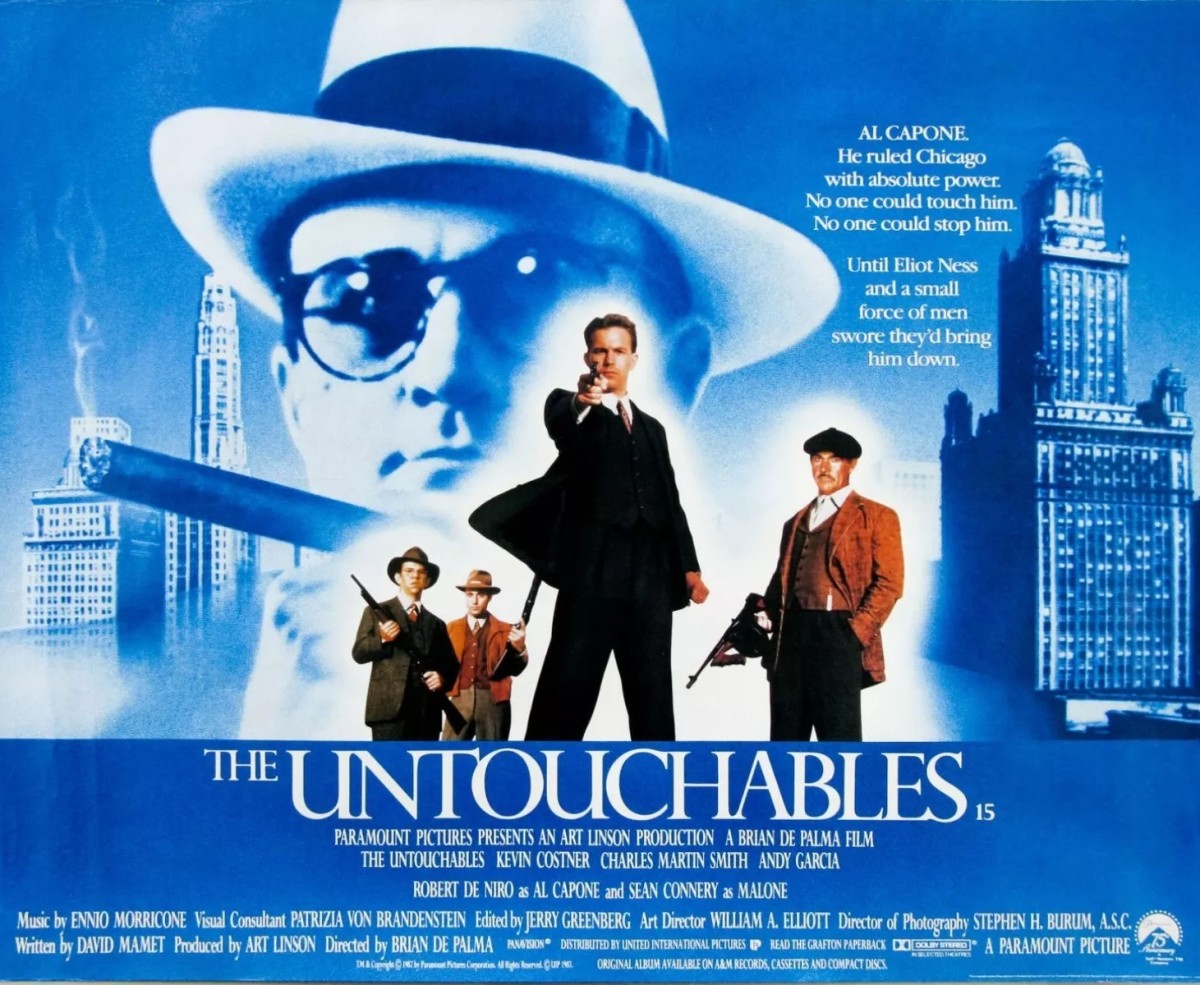

The greatest crime picture ever made, outside of The Godfather Parts I and II (1972/1974). A sledgehammer of a narrative that moves like an express train, only slowing down for a number of bravura sequences. Riddled with fabulous lines, built on great performances, and seeded early on with subsidiary characters who will later play significant roles. In any analysis it reads like a greatest hits.

The bloodied finger of Al Capone (Robert DeNiro) holding court to fawning journalists; the little girl’s plaintive cry of “Mister” before she’s blown to kingdom come; the love note included in the lunch of Elliot Ness (Kevin Costner); “poor butterfly” as the first raid goes wrong; the introduction of Malone (Sean Connery) “here endeth the lesson”; the trading of racist insults with recruit George Stone (Andy Garcia); Capone bludgeoning an associate to death with a baseball bat; in the safety of a church, Malone explaining “the Chicago way”; the first big cinematic sequence – the shootout at the border with meek accountant Oscar Wallace (Charles Martin Smith) making his bones and sneaking a drink of beer; Malone “killing” the dead man; “touchables” smeared in blood in the lift; Malone’s fistfight with crooked boss Dorsett (Richard Bradford); Malone’s murder by hitman Frank Nitti (Billy Drago); the second, and greater, bravura sequence – the shootout on the steps of the railway station; Ness pushing Nitti off the rooftop; the disbelieving Capone sentenced.

And those are just the broad strokes. Peppered throughout is the issue of Capone’s tax evasion, the crime that brings him down, with virtually all Wallace’s contribution being reading from documents relating to this. Nitti appears in the second scene, leaving the bomb that will blow the little girl to kingdom come, and again at Ness’s house.

And this is so old-fashioned that not only are we rooting for the good guys but none of those involved has marital or alcohol problems. Cops like Malone may be disillusioned but they don’t take their disenchantment out on the bottle. Anyone who talks about marriage agrees it is a good thing.

Character introduction doesn’t go down the iconic route of The Magnificent Seven (1960) or The Dirty Dozen (1967). Chicago’s Finest sneer at Ness behind his back. Another director would have been tempted into a bolder entrance for Malone. But he’s a loser, still a beat cop in middle age, and on the late shift at that. He doesn’t just know his job, detects Ness is packing a gun, but he’s capable of a sardonic quip or two. Who’d claim to be working for the humiliated Treasure Dept is they weren’t? And he’s not so stand-up as he appears, playing with a key chain like worry beads, keeps a sawn-off shotgun in his record player.

And that’s before we go into the dialog. Screenwriter David Mamet (Glengarry Glen Ross, 1992), revered as America’s greatest living playwright, turns on the style. “You can get further with a kind word and a gun than with just a kind word”; “They pull a knife, you pull a gun”; “do you know what a blood oath is?”; “team!”; “brings a knife to a gun fight”; “all right, enough of this running shit;” “can’t you talk with a gun in your mouth?” “his name wasn’t in the ledger,” “did he sound anything like that?”

And that’s before we get to the score by Ennio Morricone, his best in terms of the consistency of theme (rather than just one standout tune) since Once Upon a Time in the West (1969). Or the rocking title sequence.

Turned Kevin Costner (Horizon, An American Saga – Chapter 1, 2024) into a star, a position, with dips here and there, he’s maintained for half a century. Andy Garcia (Black Rain, 1989), too, though for a shorter duration. Not everyone was impressed by Robert DeNiro’s (The Alto Knights, 2025) florid interpretation, but I wasn’t one of them. Brought Sean Connery (The Russia House, 1990) long overdue recognition for his acting, though it’s worth remembering that the Oscar voters who gave him a standing ovation could have handed him the gong a good time before for any number of excellent portrayals.

Director Brian DePalam (Carrie, 1977) was an Oscar shut-out. And when I look at the films that took precedence in the Best Film nominations, there’s only one, Moonstruck, that I’d seek out.

This is a thunderous achievement, and I can’t wait for 2027 when Paramount surely will bring it back to the big screen for a 40th anniversary celebration.

Unmissable.