Would appear resolutely old-fashioned except for Forrest Gump (1994) adopting same premise of the main character present at major events. Here it’s issues affecting the Catholic Church between last century’s two world wars and the protagonist is an American priest, Father Stephen Fermoyle (Tom Tryon) of Irish stock, who rises to the position of Cardinal.

So we move at a relatively stately pace through abortion, inter-denominational marriage, racism, a miracle, challenging church philosophy, and Hitler’s annexation of Austria on the eve of the Second World War, in which the church played an inglorious part. Along the way Fr Fermoyle is afflicted so badly by doubt that he takes a sabbatical only for his flesh to be sorely tempted.

Astonishingly, I saw this on YouTube (it’s still there) in a beautiful 70mm print preserved by the National Film and Television Archive. The roadshow print, to be exact, which begins with a marvellous five-minute overture. Oddly enough there’s something very settling about sitting in the darkness with the curtains drawn watching a blank (black) screen and listening to the majestic score by Jerome Moross (The Big Country, 1958).

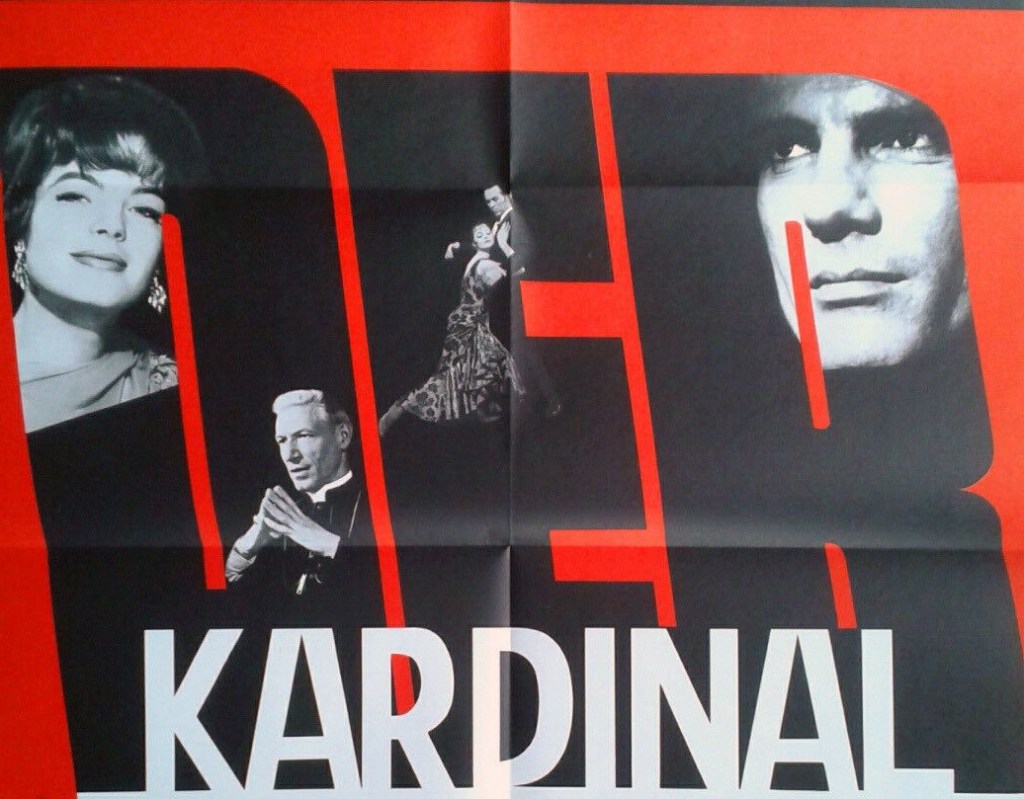

And then it’s another few minutes of a stunning credit sequence, all sunlight and shadow, before the movie begins. The movie itself is over three hours long, so if you are put off by this kind of epic now’s the time to check out. But if you do, you will miss something genuinely to be savored.

For Otto Preminger (Hurry Sundown, 1967) certainly knows how to tell a story, even one as sweeping as this. For all its pomp, he manages to retain intimacy.

Immediately after his ordination just as America enters the First World War, Fr Fermoyle faces a crisis. His sister Mona (Carol Lynley) wants to marry a Jewish dentist (John Saxon) who refuses to convert to Catholicism. Fermoyle’s advice, in keeping with the church’s stringent rules: give him up.

A noted intellectual, Fermoyle is astonished to be sent by the worldly piano-playing cigar-chomping Archbishop Glennon (John Huston) to an impoverished parish to learn humility. There, he encounters the blind faith of parishioners and a pastor, Fr Halley (Burgess Meredith), so inclined to put others first that he will not seek help for a debilitating disease.

Meanwhile Mona, now a dancer and drinker, has become pregnant, and not by the dentist. But complications arise and she is forced to choose between herself and the unborn child. According to Church doctrine, as Fermoyle, advises, abortion being illegal, the mother must die to save the baby. Mona, not the sacrificial kind, does the opposite. Fermoyle, racked with guilt, wants to quit the church. Instead, he is promoted to Monsignor, and given a two-year timeout which he spends lecturing in Vienna.

There he falls in love with Annemarie (Romy Scheider). In the nick of time, he is recalled to the States and sent to the Deep South to help the black Fr Gillis (Ossie Davis) who is being harassed by the Ku Klux Klan. In standing by his colleague, Fermoyle undergoes a brutal whipping. Promoted to bishop, he is despatched to Austria “to instruct the princes of the church in the realities of the modern world.” Unfortunately, the clergy, siding with the Nazis, presides over the marriage of Germany and Austria.

Meanwhile, he is reacquainted with Annemarie, who has married a Jewish banker, and witnesses at first-hand Nazi treatment of the Jews, her husband so fearful of his future he jumps out a window. When a mob ransacks a church, Fermoyle isn’t so intent on facing up to them and instead, with Annemarie, manages to escape.

At its best and its worst by the narrative being forced through the prism of an individual. His reactions to issues are regulated by his employers, the Church, which exerts as much control over personal thought as the Communist Party, so, in effect, it becomes a tale of a person initially bristling against authority until, it turns out, the Church shares the same antipathy to the worst of the century’s scandals, the Ku Klux Klan and the Nazis.

Father Fermoyle hardly seems suited to high office, given he is so often inclined to temptation, either in a sexual sense, or in taking the opposite view of the Church. And it’s almost as though the splendid backdrop as represented by the immense wealth of the Church has only been achieving by subjugation of the individual. That the worldly Glennon appears as the poster boy for the Church hierarchy is almost Preminger playing with the audience.

It might be sumptuously mounted, but once again Preminger takes no prisoners, showing up an institution that while purportedly set up for the benefit of mankind so often sabotages noble endeavor.

Tom Tryon (In Harm’s Way, 1965) is excellent in the leading role, personal conviction getting in the way of the easy path to the top. But the pick of the performers are the supporting stars, especially John Huston, more famous as a director (The Night of the Iguana, 1964) and here making his acting debut, and Romy Scheider (Triple Cross, 1966). Look out for Carol Lynley (Bunny Lake Is Missing, 1965), silent film star Dorothy Gish in her final movie appearance, Maggie McNamara (The Moon Is Blue, 1953) in her first picture in eight years, and John Saxon (The Appaloosa, 1966) before he was typecast as a heavy.

Otto Preminger (In Harm’s Way) directs in stately fashion from a screenplay by Robert Dozier (The Big Bounce, 1969) and Ring Lardner Jr. (The Cincinnati Kid, 1965).

Thoughtful and striking.