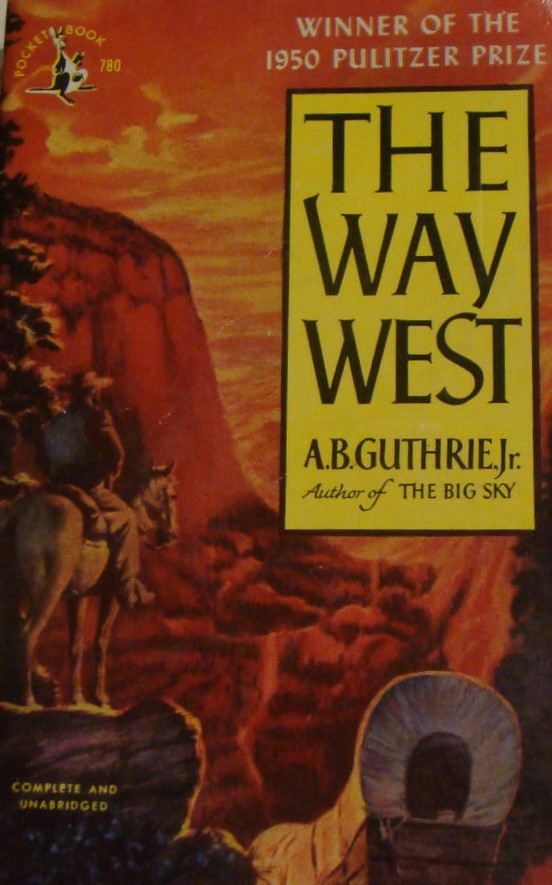

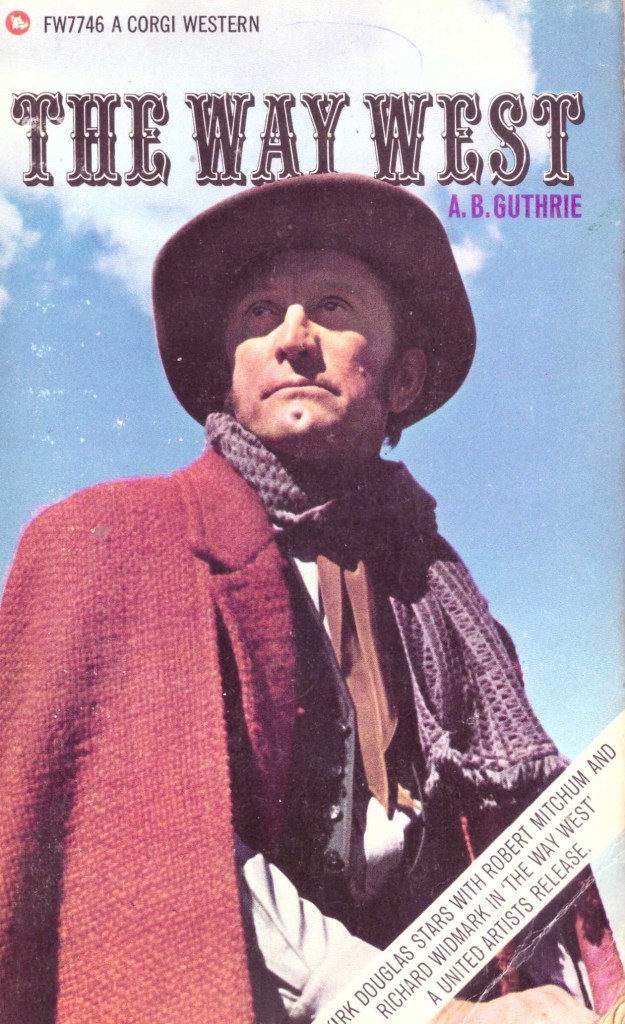

Screenwriters Ben Maddow and Mitch Lindemann earned their keep on this one. The source was a literate historical novel by A.B. Guthrie which, despite winning the Pulitzer Prize, was seen primarily as a western. In considerable detail, it covered what a wagon train heading to Oregon needed to do and know in order to make the 2,000-mile trip. It is a fascinating read, told from many points of view. But very little of the book found its way into the film.

It wouldn’t have been much of a film if the screenwriters had simply followed the book structure, for much of that was internalized, thoughts and feelings of the settlers, dramatic incident not so much. So if this was going to be a big-budget western it needed a lot more.

that the Native Americans who played a minor role in the book took center stage

on the book cover to target the expected audience.

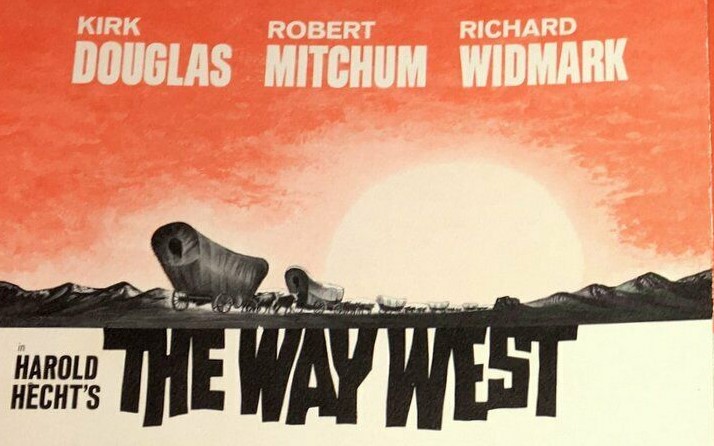

What isn’t in the book: Tadlock (Kirk Douglas) isn’t a Senator for a start, he’s not a widow and doesn’t have a child. He’s not a visionary either with some grandiose map of how he envisages the town he’ll build. He doesn’t hang a man, get a whipping or die falling over a cliff. He’s quit the wagon train long before the cliff section. And he stopped being the leader of the expedition less than halfway through the book.

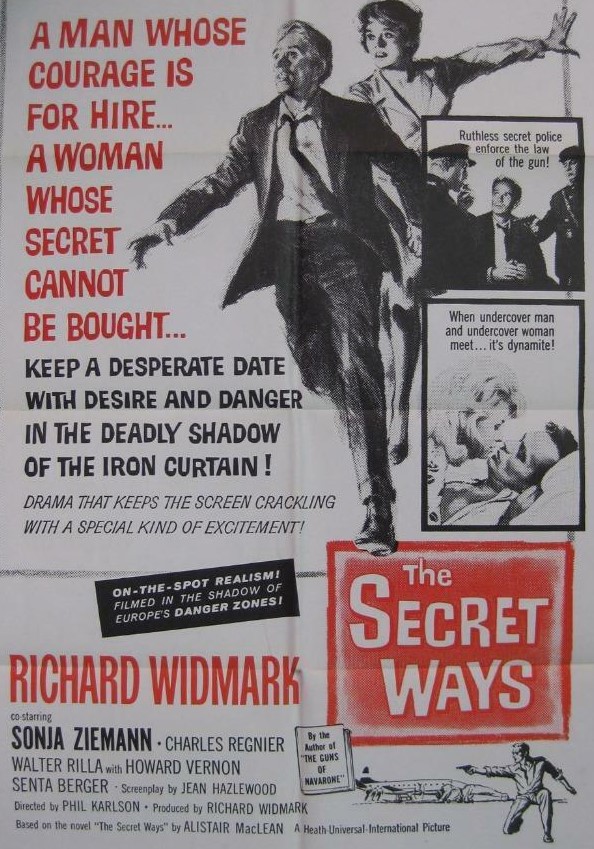

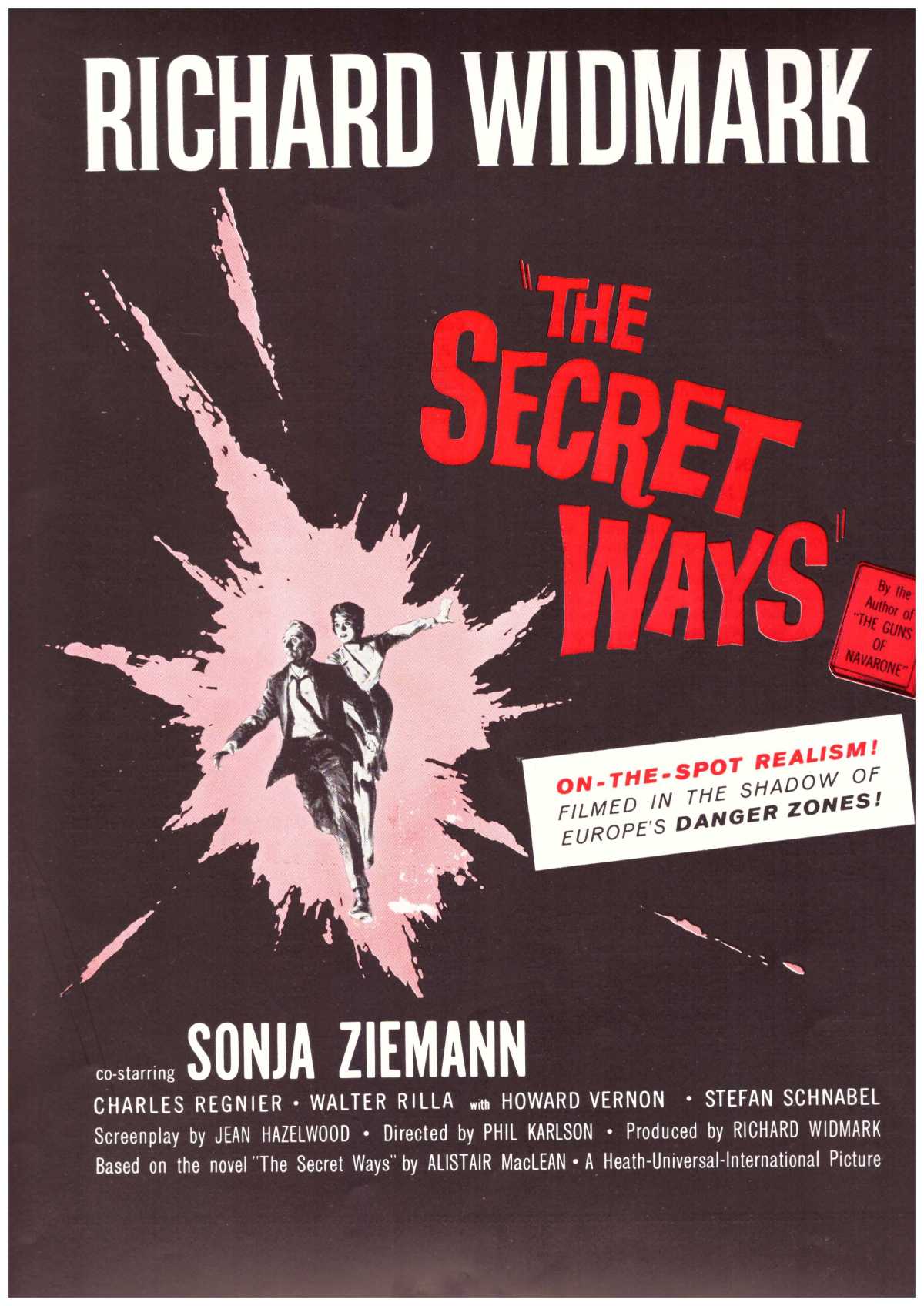

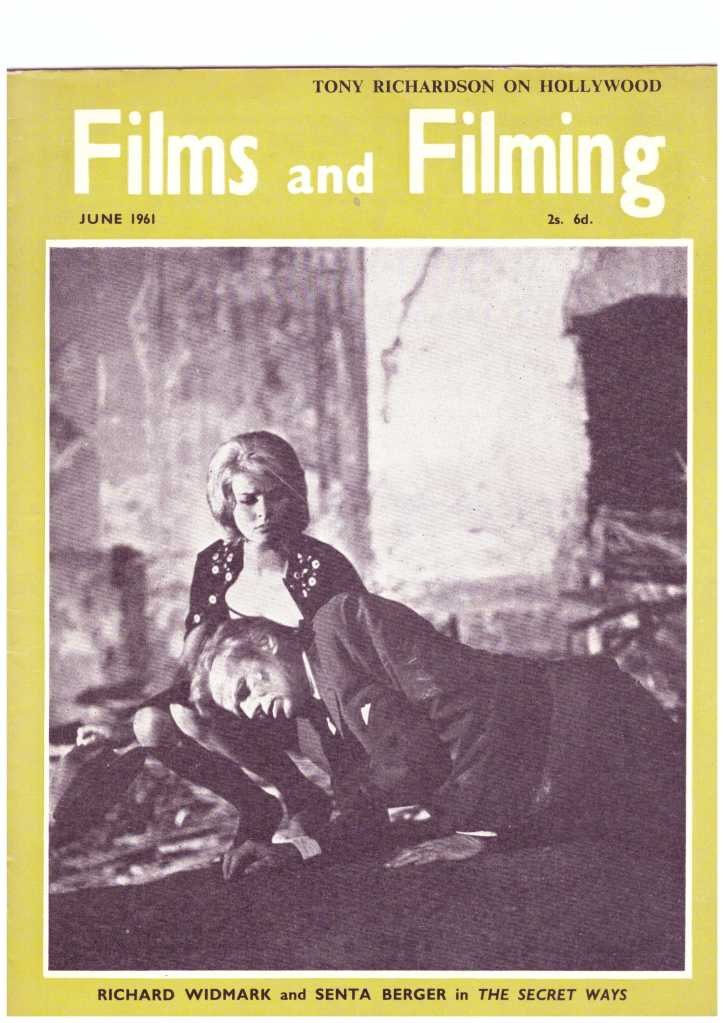

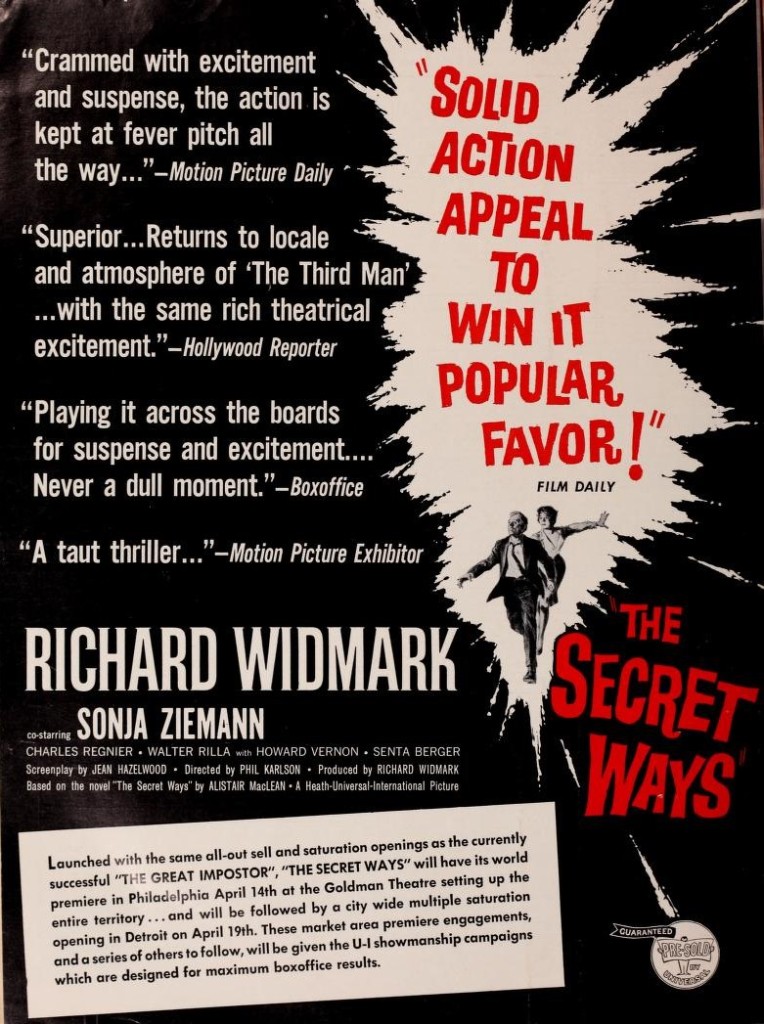

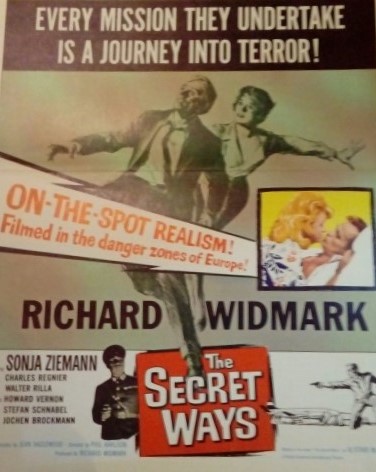

What isn’t in the book: Evans (Richard Widmark) isn’t overfond of alcohol, doesn’t create an unforced halt in order to celebrate Independence Days several days too soon, doesn’t have a grandfather clock whose loss causes him to lose his rag with Tadlock, in fact it’s he who picks the fight after discovering Tadlock intends to hang a thieving Native American.

What isn’t in the book: Dick Summers (Robert Mitchum) isn’t losing his eyesight, though recently widowed his wife wasn’t a Native American, and he doesn’t have a lucky necklace to pass on to a young man or woman.

So there’s a whole passel of wonder right there. The screenwriters have instantly dramatized all three leading characters by providing them with different attributes, making Tadlock and Summers more sympathetic than in the book, rendering Evans less sympathetic. The problem with the book’s Summers is that what makes him interesting is his lore, his knowledge of everything to do with the West, little of which translates to the screen. So providing the toughest of them all with an impediment allows him an immediate story arc.

What isn’t in the book: a Native American child is not killed by a settler, there’s no settler hanged by Tadlock to placate the warring tribe. There’s no warring tribe. There’s no race with other wagon trains at the outset and no racing across a river to get ahead of a rival. There’s no stowaway preacher either, though there is a preacher (Jack Elam). There is only one stop along the way in the film, at Fort Hall, but two in the book, the other being Laramie.

What isn’t in the book, I’m sorry to say, is the wonderful sequence of lowering wagons down a cliff, and Brownie (Michael McGreevy) marries Mercy (Sally Field) because otherwise she’s going to leave the wagon train at Fort Hall and he doesn’t make a pledge in public that her unborn child is his. And there’s no part for Stubby Kaye.

Some of the more solid emotional material is retained. The frigidity of Mrs Mack (Katherine Justice) remains, giving her husband (Michael Witney) the excuse to seduce Mercy, considerably more innocent in the book, where she is described not as sassy but awkward in adult company, “growed up in body and not in knowing.” While not loving Brownie, she marries him for convenience, though she learns to love him. Brownie gets advice on handling Mercy from Summers and much of that dialog is imported straight from the book.

From the book comes the idea of the settlers chiseling their names on the rock, of Brownie, while doing so, being captured by Native Americans and being traded back to his father.

But there are some ideas lifted from the book out of sequence that the screenwriters build up into major dramatic incidents. The river crossing at the start of the film is taken from the river crossing near the end of the book. Close to the start of the novel, Mack kills a Native American, whose tribe seek justice but are sent away empty handed by Tadlock. That becomes a key sequence in the film when Mack is hanged by Tadlock. A child is killed by a rattlesnake and that is transferred to a different father who gives full expression to his grief.

The screenwriters exacerbate the tensions between the characters, create more moments of high drama, invent the visionary element, and are responsible for the vast bulk of crisp dialogue. While the dialogue in the book sounds authentic, it lacks the brittleness and thrust of the words spoken in the film.

A.B. Guthrie was a celebrated American novelist, a journalist who had come to fiction late, over 40 when he produced his first book, a mystery novel set in the West. But after winning a fellowship to Harvard, his writing took a literary turn, and his West did not take the traditional romanticized view. Two of his novels had been filmed – The Big Sky (1952) starring Kirk Douglas and These Thousand Hills (1959) directed by Richard Fleischer – and he had written an Oscar-nominated screenplay for Shane (1953), based on the Jack Schaefer novel, as well as for The Kentuckian, based on the Felix Holt book. The Way West had become such a touchstone for originality and an acclaimed masterpiece that it seemed impossible to turn it into a film.

Whether the film’s negative critical reaction and audience disregard was down to the screenplay veering so far away from what was considered a classic novel is hard to say. This is a very good example of a book that appeared unfilmable being somehow turned into a more than watchable film.

And I can recommend the book.