Despite being made at the opposite end of the decade to Loss of Innocence/The Greengage Summer (1961) this has a number of similarities, in the main the star-making turn, this time from Ali McGraw in her debut and, though playing a slightly older and much wealthier character, she is also a woman in transition, from puppy love to true love, not entirely in control of her emotions and not willing either to accept responsibility for her actions.

Richard Benjamin, in his first starring role, plays the sometimes gauche, much poorer, more responsible, object of her affections. He’s only connected by religious upbringing to The Graduate’s Dustin Hoffman, far more relaxed with women and comfortable in his own persona. The camera loved McGraw the way it did Susannah York, but in these more permissive times, and given the age difference, there was much more the screen could show of the star’s physical attributes.

I was surprised by the quality of McGraw’s performance, expecting much less from a debutante and ex-model (and studio boss Robert Evans’ fiancée) but she is a delight.

Supremely confident Brenda (Ali McGraw) enjoys a life of privilege and engages in witty repartee with the more down-to-earth Neil (Richard Benjamin) who doesn’t know what to do with his life except not get stuck with a money-making job. He would much rather help a young kid who likes art books.

It’s not a rich girl-poor man scenario but more a lifestyle contrast and both families are exceptionally well portrayed. Brenda’s father Ben (Jack Klugman) has sucked the life out of exasperation while her uptight mother (Nan Martin) has to cope with an oddball son (Michael Meyers) and a spoiled brat of a younger sister (Lorie Shelle). It’s somewhat reassuring that money doesn’t prevent family politics getting out of hand.

But in the main it’s a lyrical love story well told. The zoom shot had just been invented so there’s a bit over-use of that but otherwise it zips along. A major plot point provides a reminder of how quickly men took advantage of female emancipation, the invention of the Pill dumping responsibility for birth control into the woman’s lap, leaving the male free to indulge without the risk of consequence.

In other words, it was still a man’s world. Of course, without the Pill, it would be a different kind of story, romance tinged with fear as both characters worried about unwanted pregnancy and stereotypical humour as the man purchased – or fumbled with – a rubber. Acting-wise Ali McGraw is pretty game until the final scene when her inexperience lets her down. I’m not sure I went for the pay-off which paints McGraw in unsympathetic terms and lets Benjamin off rather lightly.

The romantic stakes were considerably lower than in McGraw’s sophomore outing, Love Story (1970) and for both characters it was not the defining moment of their lives, more a rite-of-passage.

Director Larry Peerce (The Incident, 1967) takes time to build a believable background and uses humor to defuse what could have become an overwrought melodrama. Arnold Schulman (The Night They Raided Minsky’s / The Night They Invented Striptease, 1968) was Oscar-nominated for his screenplay based on the Philip Roth bestseller.

No one ever knows why the camera takes to an individual and given this was long after Hollywood had stopped trying to invent stars it was a wonder that Ali McGraw was turned into an marquee attraction. But there was such a lightness to her screen persona it was a surprise she didn’t become a contender for screwball comedy.

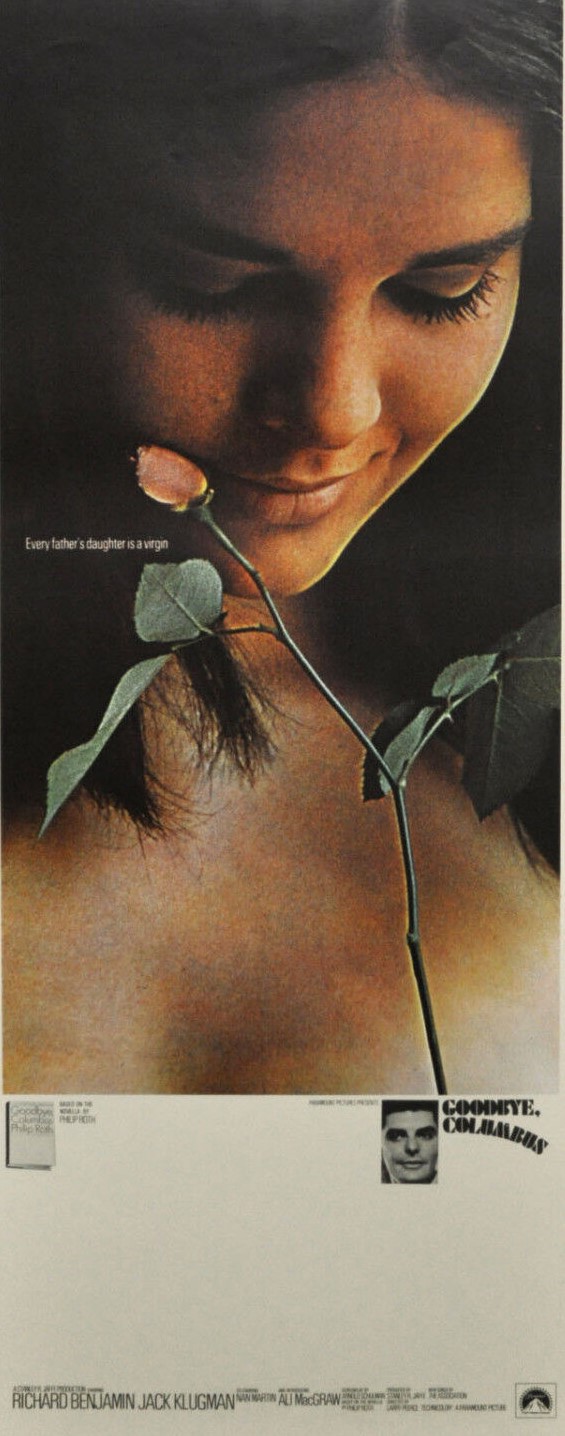

Richard Benajmin (Catch 22, 1970), also making his movie debut, does his best but can’t prevent his co-star stealing the show. It must have been galling for the young actor who must surely have believed he was the one being groomed for stardom after the success of television show He and She (1967-1968). He suffered the indignity of his face being reduced to a postage stamp – almost an afterthought – on a poster on which McGraw dominated. He might have taken top billing but in contractual terms that only permitted his name to come first and could not dictate how he was presented.

All in all I was surprised how much I enjoyed it.