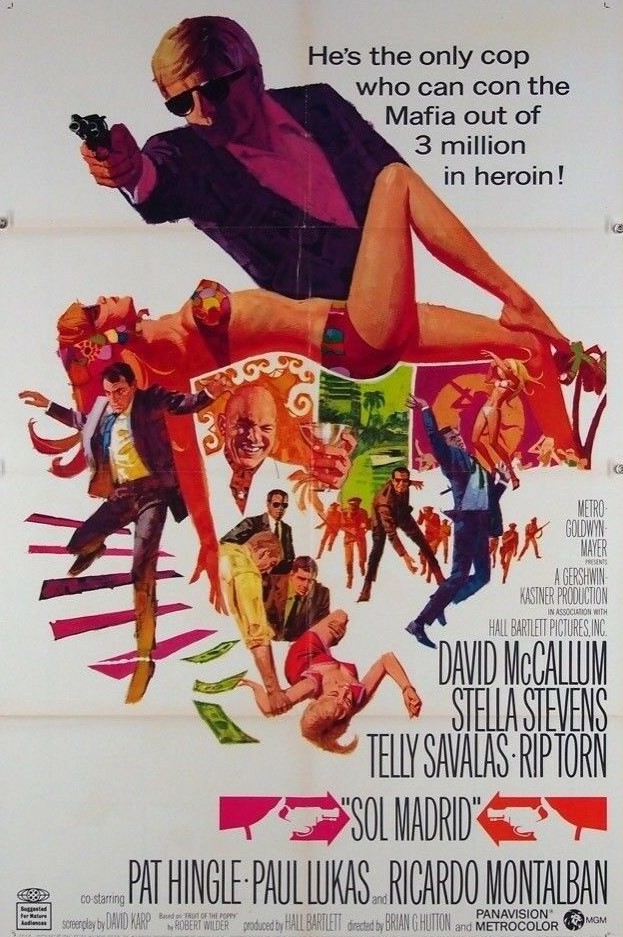

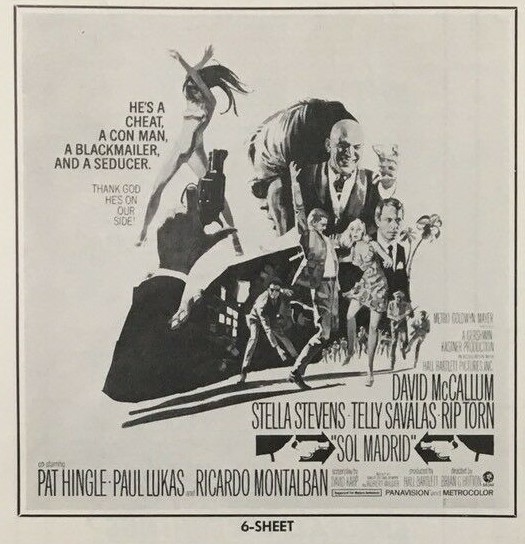

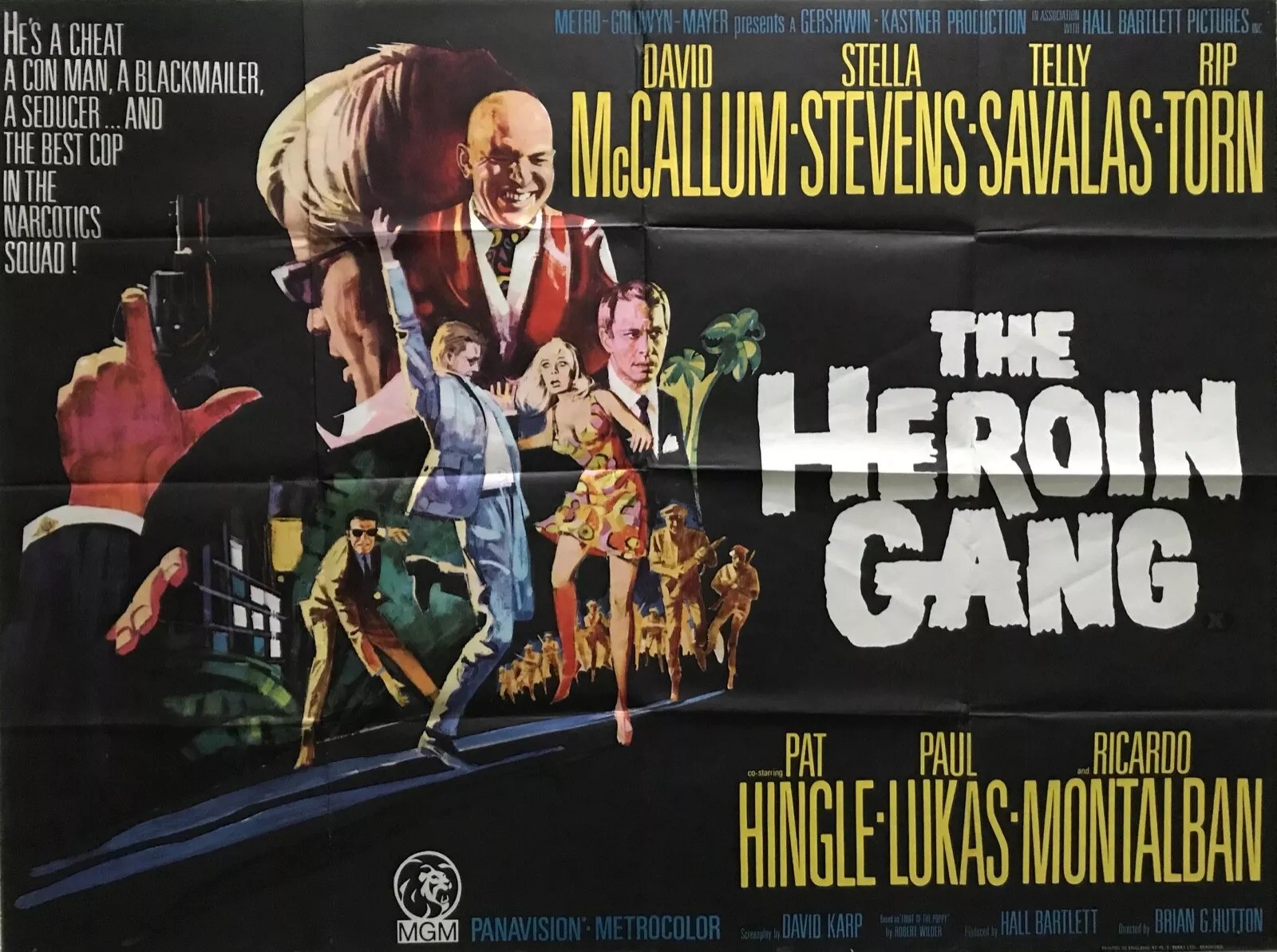

Was it David MacCallum’s floppy-haired blondness that prevented him making the jump to movie action hero because, with the ruthlessness of a Dirty Harry, he certainly makes a good stab at it in this slightly convoluted drugs thriller? Never mind being saddled with an odd moniker, the name devised surely only in the hope it would linger in the memory, Sol Madrid (David MacCallum) is an undercover cop on the trail of the equally blonde, though somewhat more statuesque, Stacey Woodward (Stella Stevens) and Harry Mitchell (Pat Hingle) who have scarpered with a half a million Mafia dollars. Mitchell is the Mafia “human computer” who knows everything about the Cosa Nostra’s dealings, Woodward the girlfriend of Mafia don Villanova (Rip Torn).

Sol tracks down Woodward easy enough and embarks on the audacious plan of using her share of the loot, a cool quarter of a million, to fund a heroin deal in Mexico with the intention of bringing down both Mexican kingpin Emil Dietrich (Telly Savalas) and, using the on-the-run pair as bait, Villanova. A couple of neat sequences light this up. When Sol and Woodward are set upon by two knife-wielding hoods in a car park, he employs a car aerial as a weapon while she taking refuge in a car watches in terror as an assailant batters down the window. Sol has hit on a neat method of transferring the heroin from Tijuana to San Diego and that is filled with genuine tension as is the hand-over where Sol with an unexpected whipcrack slap puts his opposite number in his place.

Meanwhile, Villanova has sent a hitman to Mexico and when that fails turns up himself, kidnapping Woodward and planning a degrading revenge. Most of the movie is Sol duelling with Dietrich, suspicion of the other’s motives getting in the way of the trust required to seal a deal, with Mitchell, who has taken refuge in Dietrich’s fortified lair, soon being deemed surplus to requirements. Various complications heighten the tension in their flimsy relationship.

Sol Madrid is Dirty Harry in embryo, determined to bring down the gangsters by whatever means even if that involves going outside the law he is supposed to uphold, incipient romance with Woodward merely a means to an end.

David MacCallum (The Great Escape, 1963) certainly holds his own in the tough guy stakes, whether trading punches or coolly gunning down or ruthlessly drowning enemies he is meant to just capture, and trading steely-eyed looks with his nemesis.

It’s a decent enough effort from director Brian G. Hutton (Where Eagles Dare, 1968), but is let down by the film’s structure, the expected confrontation with Villanova taking far too long, too much time spent on his revenge with Woodward, for whom audience sympathy is slight. Just at the time when Hollywood was exploring the fun side of drug taking – Easy Rider just a year away – this was a more realistic portrayal of the evil of narcotics.

It is also quite prescient, foreshadowing both The Godfather Part II (1974) in the way Villanova has modernised the organisation, achieving respectability through money laundering, and the all-out police battles with the Narcos. And there is a bullet-through-the-glasses moment that will be very familiar to fans of The Godfather (1972), and you will also notice a similarity between the feared Luca Brasi and the Mafia hitman Scarpi (Michael Conrad) here.

The action sequences are excellent and fresh. Think Madeleine cowering in terror as the car window is battered in No Time to Die (2021) and you get an idea of the power Hutton brings to the scene of a terrified Woodward hiding in the car. Incidentally, you might think MacCallum was more of a secret agent than a cop with the cold-blooded ruthlessness with which he dispatches his enemies.

Stella Stevens (Rage, 1966) is the weak link, too shrill and not willing to sully her make-up or hair when her role requires degradation. Her role is better written (“I never met a man who didn’t want to use me”) than Stevens can deliver and she gets a clincher of final one. Telly Savalas (The Dirty Dozen, 1967) surprises by delivering a playful villain, though the trademark laugh is in occasional evidence whereas Rip Torn is all villain. Ricardo Montalban (Madame X, 1966) is Sol’s Mexican sidekick and Paul Lukas, a star of the Hollywood “golden age”, puts in a fleeting appearance. Written by David Karp (Che!, 1969) and Robert Wilder (The Big Country, 1958).

Proved a winner for Brian G. Hutton – next gig Where Eagles Dare. Less so for David MacCallum – next outing The Mosquito Squadron (1969).

Has its moments.