Apparently to everyone’s surprise the extended version of Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Ring (2001) broke into the box office top ten the weekend before last with The Two Towers (2002) not far behind. Already cinemas are gearing up for a swathe of 1999 reissues (25th anni don’t you know) including The Matrix and American Pie and IMAX is already setting aside screens for the 10th anniversary re-release of Interstellar (2014) later in the year.

With the demise of the DVD and the domination of the streamers, you would have thought there was no room anywhere for old movies returning to the big screen. But, historically, reissues always returned to save the day, most commonly when the industry was low on product. That was generally the most obvious reason and splurges of revivals occurred in the early 1920s, late 1930, post WW2 and the mid-1950s.

But there were other reasons. I could give you chapter and verse about the reissue since I wrote a book about it, but to save you ploughing through those 250,000 words, I’ll stick to the salient points. Mary Pickford and Charlie Chaplin kicked off the revival business. In the silent era there were few prints of any new picture, often less than 100, so theaters which couldn’t afford the price of the new offerings of the King and Queen of Hollywood just brought back their old ones.

For a time, in the 1920s and 1940s, studios just retitled pictures and brought back oldies as newbies until the law caught up with them. And in another dodgy piece of business, just before Hollywood sold a bunch of titles to television, they were inclined to throw them out for one last roll of the box office dice, infuriating exhibitors and moviegoers alike.

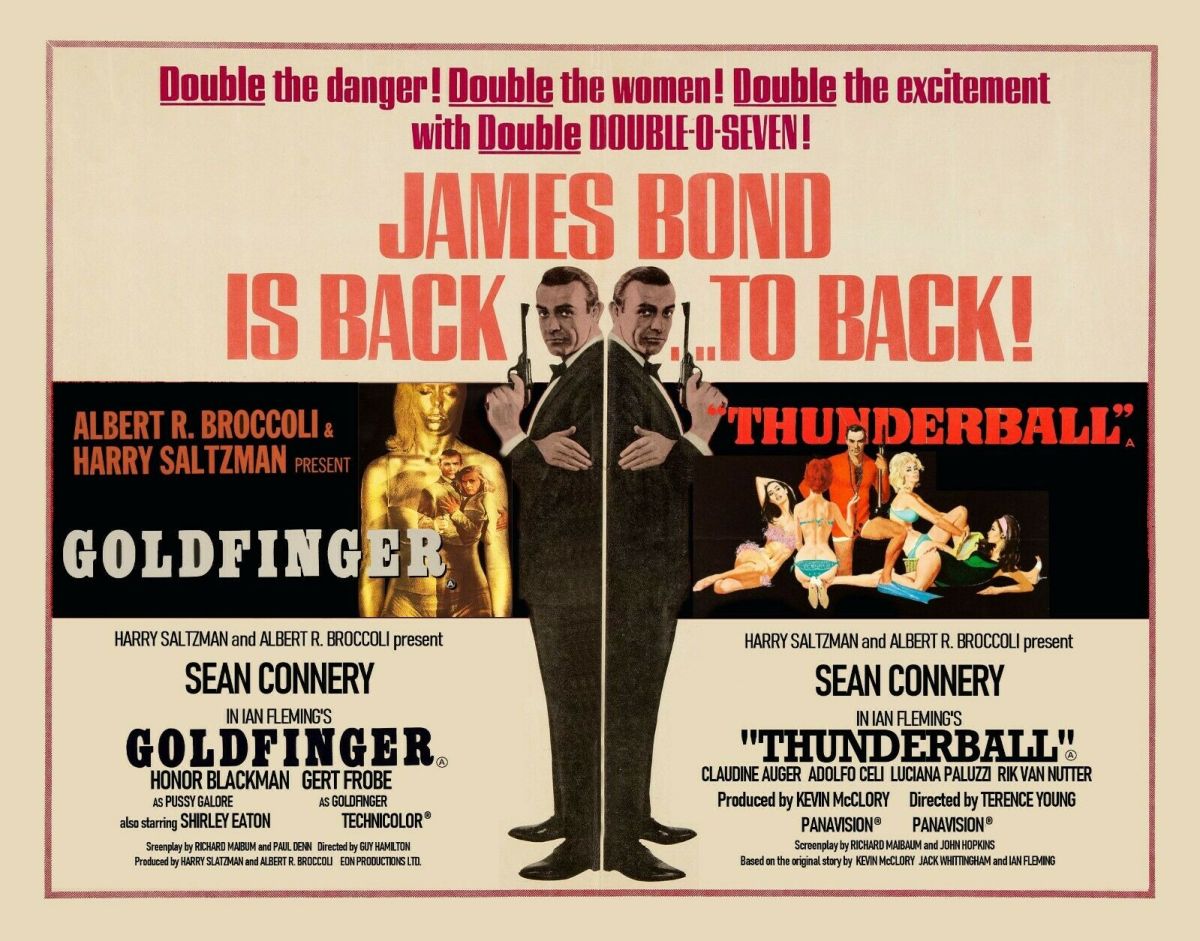

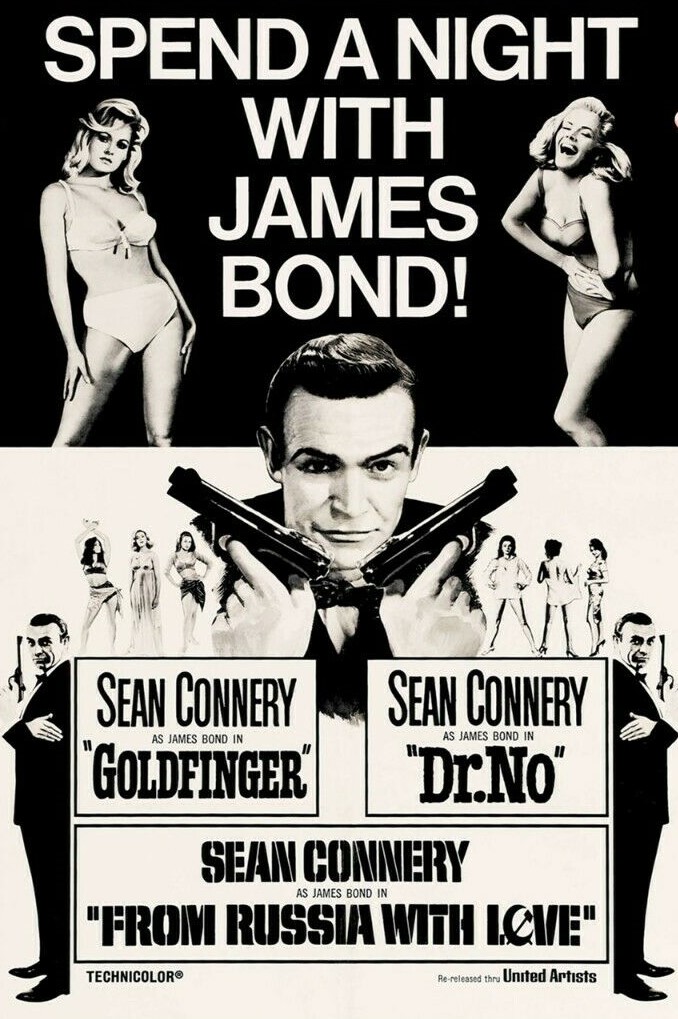

But the big boom in reissues was nothing to do with shortage and more the realization that, as we are more fully aware these days, punters will go back again and again to see a favorite. The James Bond bandwagon kicked off this particular spree but by the 1970s many films – Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), Billy Jack (1971) and Jeremiah Johnson (1972) – made more on revival than they did first time around. Studios began to build into a film’s release a reissue – they even invented a phrase for it “the wind-up saturation.”

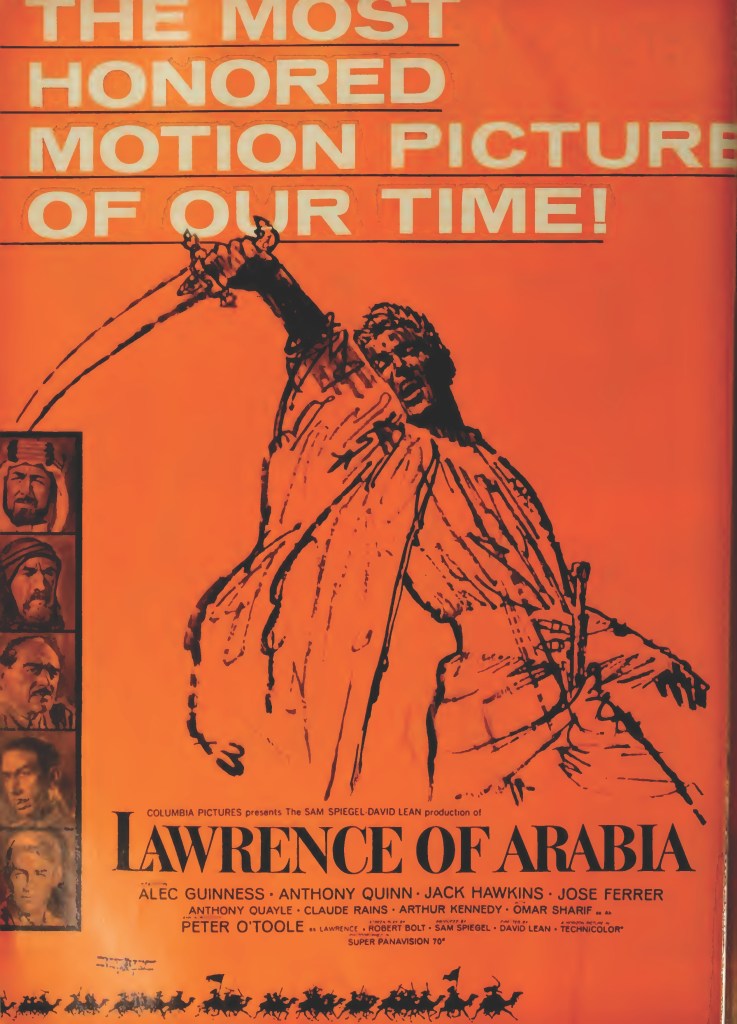

And when those particular wells began to run dry as ancillary – video, cable – took over, the art film rode to the rescue. Neglected masterpieces like Abel Gance’s Napoleon (1927) or Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) were revamped while disgruntled auteurs of the caliber of David Lean found new audiences for different versions of Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Ridley Scott took this notion to the extreme with endless iterations of Blade Runner (1982). Then Imax and 3D came into play and scooped up gazillions for further airings of Pixar or Disney classics or Titanic (1997).

However, the reissue heyday looked dead and buried once movie lovers cottoned on that old movies were constantly were only being brought back for a one-day showing because they had gone through the 4K loop, but with DVDs able to add buckets of extras, commentaries and histories, that became the de facto location for revivals.

But then Covid struck and cinemas, bereft of product, looked once again to oldies. While nobody was partying like it was 1999, it was both astonishing and satisfying to studios that older movies could take up some of the product slack. While most of the movies taking a second bite were made this century and some coming back not long after initial release, there have been a good few surprises in the mix, not least that the anniversary marketing tag was not always in play.

Take the 2020 revivals for example. Topping the list was Mamma Mia (2008) with a whopping $84.6 million gross worldwide – plus $7.2 million for the 2018 sequel – followed by Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (2001) scooping up a wizard $31.5 million. Gravity (2013) with Sandra Bullock adrift in space notched up $24.8 million. You’d be taking something of a marketing gamble to reckon American election year could boost an old political movie but that was the case for The Post (2017), sterling cast of Meryl Streep and Tom Hanks aside unless Streep was surfing a Mamma Mia wave, which blocked out $13.9 million. Bohemian Rhapsody (2018) continued to clock up the bucks, with $7.1 million.

The traditional upswell for U.S. animated classics was long gone but Moana (2016) cleared another $21.7 million while The Lion King (1994) chomped through another $5.6 million in the wake of the remake.

Avatar (2009) was the big noise of 2021, lifting $57.9 million a year ahead of the long-awaited sequel. Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone kept going, an extra $15.5 million and, guess what, there was a welcome audience for Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Ring with $8.9 million.

And the original Avatar wasn’t done. In fact the following year – 2022 – it did even better, an awesome $76 million in the kitty. Given that James Bond was the original source of so much reissue wealth it was fitting that 10th anniversary status was bestowed on Skyfall (2012), with the studio rewarded by a healthy $33 million. In true Martin Scorsese style, that is by not fitting with convention, The Wolf of Wall St (2013) celebrated its ninth anniversary and plundered $15 million.

James Cameron and Christopher Nolan in 2023 went head to head for the title of reissue king. Titanic – again – won with $70 million. Interstellar – another ninth anniversary celebrant – took home $44 million. The original Toy Story (1995) resurfaced with $27.5 million and in a 30th anniversary gesture The Nightmare Before Xmas (1993) romped off with $10.4 million.

And what of this year? Star Wars: Episode 1 – The Phantom Menace (1999) leads the pack with $19.4 million. As I mentioned 1999 is getting fair old fist-pump, some marketeers with little in the way of cinematic memory going so far as to claim it was cinema’s best-ever year. That kind of all-encompassing revival branding was rolled out for Columbia’s 100th Anniversary celebrations which saw a bundle of old pictures brought out under that aegis for a total $6 million gross. The second part of Dune brought further viewings for Dune (2021) and $3.9 million. Shrek 2 (2004) was 20th anni fare – a further $2.4 million.

Yet another revival of Alien (1979) – 45th anni if you’re interested – snapping up $2.3 million – ahead of the latest in the series was no surprise but a return for Hereditary (2018) was, this Toni Collette number reflecting its growing cult status with an extra $2.4 million.

The Lord of the Rings trilogy this year has already snagged a collective $7.8 million, Fellowship in front with $3.4 million, Two Towers on $2.4 million and Return of the King with $2.2 million.

So it looks like, at least for the time being, and as long as anniversaries provide marketing heft, the reissue will keep going,

Next up, as part of the Columbia reissue juggernaut, Lawrence of Arabia (1962). As it happens, there’s a Behind the Scenes on that one on the blog.

SOURCES: Brian Hannan, Coming Back to a Theater Near You, A History of Hollywood Reissues 1914-2014 (McFarland, 2016); Box Office Mojo.