The “lost” Robert Mitchum picture, never seen on VHS or DVD, but now turning up on YouTube.

Elephants have little proven appeal for audiences. From Dumbo (1941), Hannibal (1960), Billy Rose’s Jumbo (1962) and Hannibal Brooks (1968) through to Dumbo (2017) and Babylon (2022), the story is one of negative impact on box office. Baby elephants are maybe a different story – see Hatari! (1962) – but there’s very little that’s cuddly about the adult version and their main purpose appears to be to annoy a major stars initially and then go on a rampage that either hinders or helps said star. If you’re acquainted with elephants, you’ll notice this is of the tameable Asian variety rather than the untamed African.

The unnamed beast here would fall into the former category except the eponymous Mister Moses (Robert Mitchum) – real name Joe – can talk to the animal in a language it understands and persuade it to show off its parlor tricks, enhancing Moses’s status among a small community in Kenya. Moses is a con-man-cum-diamond smuggler, rescued from a river, specifically the reeds growing there that offer a Biblical connection to the natives.

The Bible plays a significant role here, though the natives don’t fall for the Noah story as explained by missionary (Alexander Knox). They are, like Native Americans, being driven off their land by the arrival of a dam which will flood their traditional grounds. Their cattle have not been included in the grand plan to airlift the entire community. So they refuse government help, hence the need to embark on a 300-mile trek.

Moses, a dodgy character with “an allergy to badges of authority”, is blackmailed by the missionary’s daughter Julie (Carroll Baker) and ends up doing the job of her fiancé, district commissioner Robert (Ian Bannen), to shift the natives off their land. He’s got some parlor tricks up his sleeve, too, including a flame-thrower which, again the old Biblical touch, he can employ to burn a bush, thus endearing himself as a leader.

Naturally, enough, though staid, Julie finds herself attracted to Moses, a somewhat laid-back character with quite a line in hip patter. But it’s quite a stretch for Julie to be seduced by his knowledge of classical literature, namely the Andromeda-Perseus tale. Not everyone takes to Moses’ leadership, saboteurs steal the map and the compass. And it’s no surprise when someone finds another purpose for the flame-thrower. There’s a bad witch doctor Ubi (Raymond St Jacques) to be put in his place, and Joe rises out of his lethargy long enough to dispose of a couple of villains.

With the emphasis on the Biblical, Joe is called upon to “part the waters” Exodus-style. Disappointingly, this is a bit of a parlor trick. It had me wondering how the heck he was going to do that, with just a flame thrower and an elephant at his disposal, and also given that the sole purpose of rivers in African movie vernacular is so that the leading lady can bathe in one. Since the aforementioned river is nothing more than the outcome of another dam, Moses is clever enough to simply persuade the dam superintendent to – miracle of miracles – to turn off the water.

There’s enough going on to maintain interest and the will-she-won’t-she element is well-handled and there’s a good final line, “What’ll I do for laughs?”

Robert Mitchum has been here before (Rampage, 1963) but this time is on the side of the animals. Of course, the main interest is not how well he gets on with the elephant but whether he strikes sparks with a Carroll Baker (Harlow, 1965) eschewing her normal sexy persona. A cross between Hayley Mills and Deborah Kerr, Baker doesn’t quite suggest bottled-up sexual energy fizzing to get out, but then that wouldn’t be in character. It’s not in The African Queen league in terms of screen partnerships but it’s certainly workable enough.

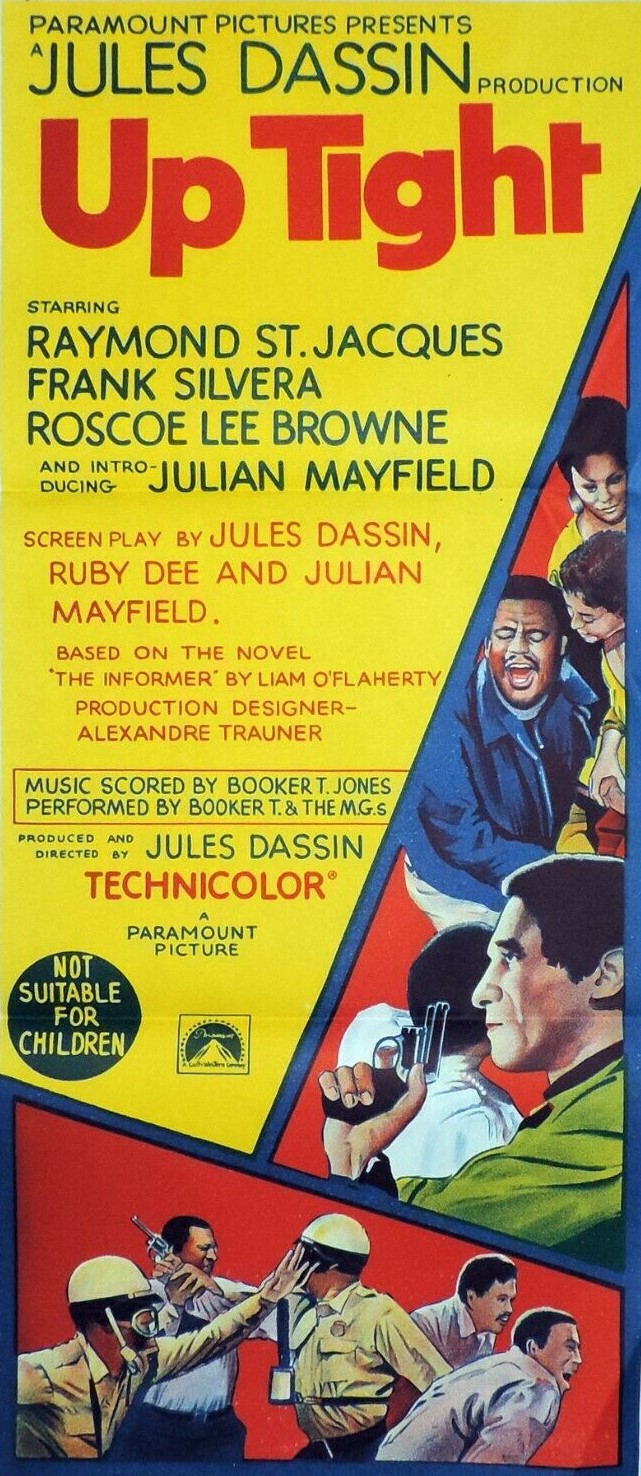

Ian Bannen (The Flight of the Phoenix, 1965) is at his scowling best although Raymond St Jacques (Uptight, 1968) gives him a run for his money. Director Ronald Neame (Gambit, 1966) proved as adept at handling the big-name stars as the animals without it being acclaimed as a famous “lost” work of Mitchum. The screenplay by Charles Beaumont (Night of the Eagle/Burn, With, Burn, 1962) and Monja Danischewsky (Topkapi, 1964) was based on the novel by Max Catto (Seven Thieves, 1960).

A pleasant enough diversion.