I’m going out on a limb on this one. I don’t think anyone’s done anything but give it a cursory examination and mark it down as a standard programmer of the era. But I saw a lot that was considerably impactful.

Generally speaking, although the war picture had gradually shifted from the gung-ho to the more realistic (Operation Crossbow, 1965, Von Ryan’s Express, 1965), it’s generally accepted that it was The Dirty Dozen (1967), Beach Red (1967) and Play Dirty (1968) that ushered in the new era of authenticity and violence.

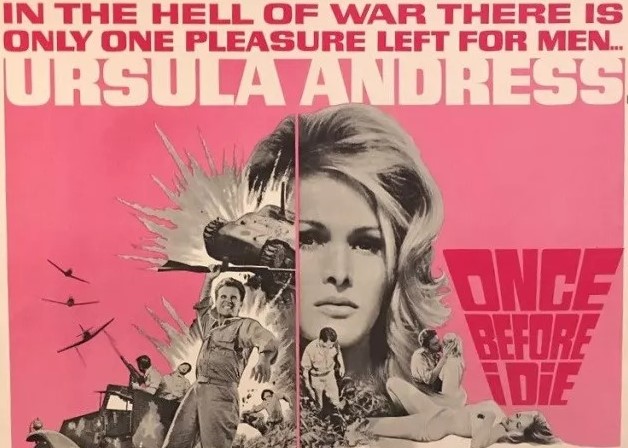

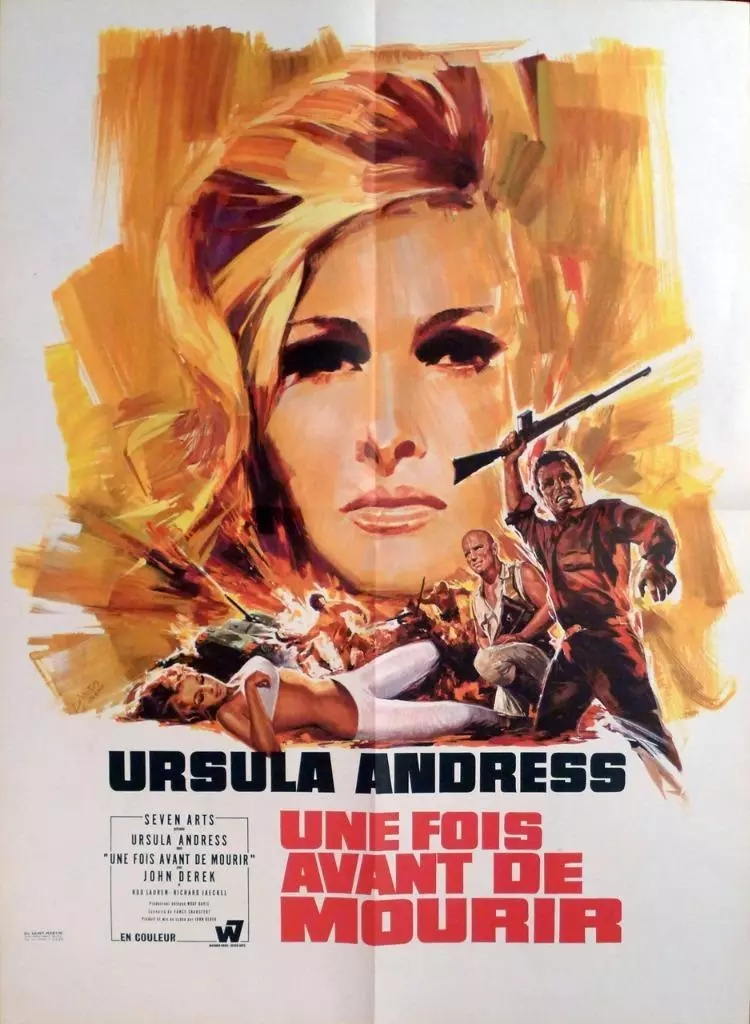

Oddly enough, this little picture, minus the bloodletting, was the bridge. It’s way tougher than you would expect for a low-budget picture only ever intended to fill out the lower half of a double bill and never going to catch the eye of a critic hoping to find an unknown movie to punt.

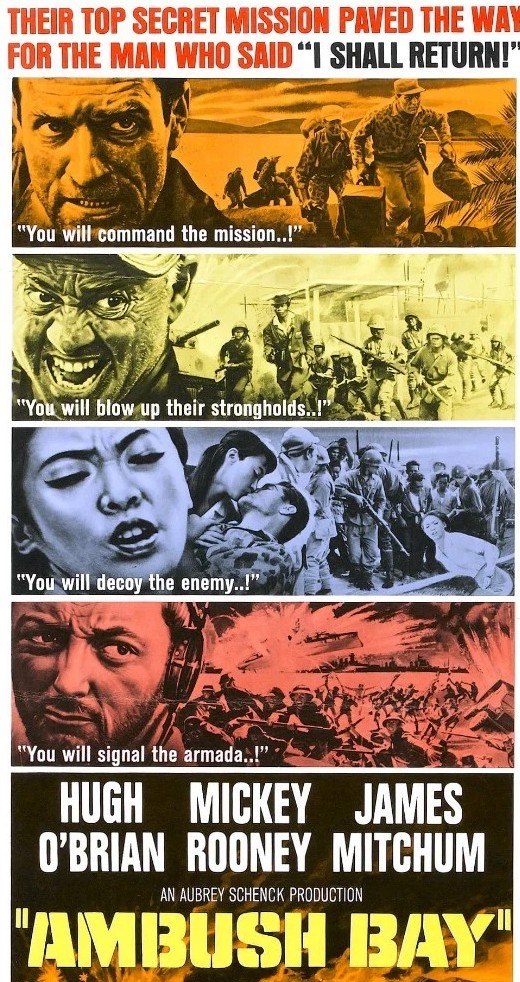

Let’s start with the ruthlessness. A bunch of Yanks on a secret mission in the Philippines are hounded by Japanese soldiers. At their first encounter, knives are the weapon of choice so as not to attract attention. We don’t see the knives going in but we hear them slicing into flesh. They capture one of the enemy who begs to be taken prisoner but nobody’s got time to bother with such niceties so they tie him to a tree and come morning he’s dead. Rather than give away their own position, they don’t fire on the pursuing Japanese which results in one of their own being killed. A female American-born Japanese spy, convinced her natural charms can distract the Japanese, volunteers at one point to stay behind, even if that means becoming the sexual plaything of the Japanese commander and then passed on to his men. And when that ploy fails she is ruthlessly sacrificed.

There are other narrative reversals. The Dirty Dozen, for example, begins with a lengthy introduction to each of the condemned men. Here, as the team prepare to land on the Philippines, we are introduced, via voice-over, to each of the team. And then you learn that the real reason for this is that we’ll count up the number of men in the group and become aware that they are gradually being whittled away.

And then there’s the voice-over itself. This not being one of those post-modernist numbers where the narrator is speaking from beyond the grave, audiences know that a narrator is a survivor. But what they’re not going to guess is that he’ll be the only survivor.

Or that he least deserves to survive. Private Grenier (James Mitchum) is a rookie – “six months ago he was stacking shoe boxes” – and he’s truculent and troublesome. His only job is to keep the radio safe, excused fighting duties so that he can broadcast to the waiting General MacArthur the outcome of the mission. But he’s as useless at guarding the radio as he is at everything else and the radio is shot to pieces. He’s so dumb he doesn’t realize the purpose of a Japanese tea house.

There’s not an ounce of the gung-ho. The dialog is delivered in an undertone. Nobody makes a meal of any line of dialog no matter ho juicy. Everything undercuts. When Commander Sgt Corey (Hugh O’Brian) plans to go into serious harm’s way his number two Sgt Wartell (Mickey Rooney) asks what will happen if he doesn’t come back. In matter-of-fact tones, but without the snap of someone thinking he’s delivering a great line, Corey replies, “You get a field promotion and an extra eight bucks a month.”

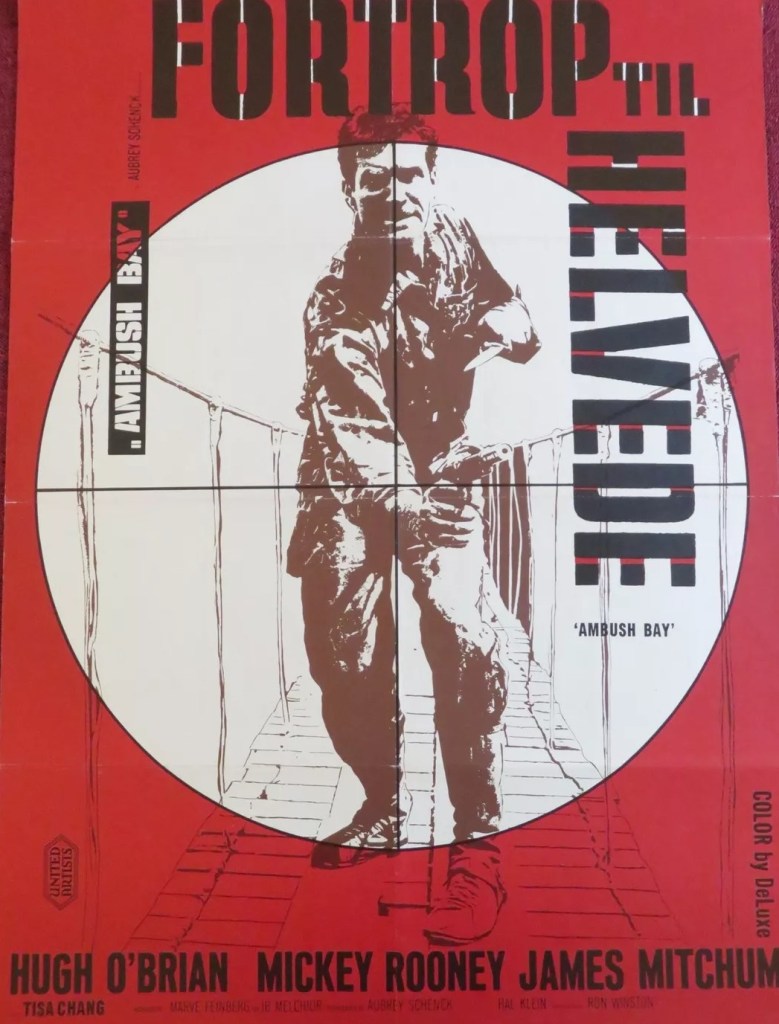

The Ambush Bay of the title is supremely ironic. It’s the Americans who are going to be ambushed. The Japanese have seeded the sea-bed of the beach where they guess the Americans are going to land with mines. Nothing unusual there. Minesweepers will clear the path. Except these are unusual mines, anchored to the seabed and only loosened by remote control by the enemy.

The initial mission is just to locate the aforementioned spy Miyazaki (Tisa Chang) who turns out to be a sought-after sex worker in the tea house. But when the radio is out of action, they have to disable the radio tower controlling the mines. By this point they’re down to just two men, Corey and Grenier.

Grenier has the ingenious plan of draining fuel from a truck to make a Molotov cocktail, toss it into a fuel dump and in the confusion make their way to the radio tower. Even at this late stage, reversals come thick and fast. Great idea – you got a match? Nope. But the lorry driver is smoking. He discards a lighted cigarette. But when he gets out of his cab he grinds the cigarette with his foot. Luckily, they can revive it.

All the way the dialog is like loaded dice. “Idiot,” muses Grenier, “that’s the nicest thing he’s said to me.”

Miyazaki has some choice lines. “If you’re dead that won’t help me.” And, encountering Corey’s disbelief at her gender, “Suppose I refused to believe you were my contact.” And in the understated manner of every individual, of the leering Japanese commander, she notes, “He desires me, I think that’s the phrase.”

Visually, this isn’t littered with gems. Most of the visuals are under-stated, brutality generally off-camera but there’s one unforgettable scene. The Japanese commander, having been distracted by Miyazaki puts his pistol in his holster. A few minutes later, realizing he has been duped, he takes it out of its holster.

Hugh O’Brian (Ten Little Indians, 1965) is superb as the non-scene-stealer-in-chief. Mickey Rooney (The Secret Invasion, 1964) has less opportunity for grandstanding than in most of his pictures. And surely this is the recently-deceased James Mitchum’s (In Harm’s Way, 1965) best role, as he shifts from amateur to professional. If you’re looking for an understated scene-stealer Tisa Chang (better known for her stage work – she only appeared in five films) is choice.

Directed by Ron Winston (Banning, 1967) from a script by Ib Melchior (Planet of the Vampires, 1965) and Marve Feinberg in his debut.

The lowest-budgeted film, just $640,000, in the 1966 release schedule of United Artists, on a cost-to-profit scale this proved one of its most successful pictures hammering out $1.7 million in rentals.

Worth going out on a limb for.