Easy credit led to a boom in the standard of living but also created global recession after the sub-prime mortgage scandal. Back in the day you couldn’t borrow money except from a bank and they only lent to people with money. To get a mortgage you needed to prove you could save, you required at least a 10 per cent deposit before any bank would loan you money for a mortgage, and you needed to go through a stiff criteria test. Even then, you were at the mercy of inflation. If you were absolutely desperately you could go to money-lenders and pay back inflated sums, the notorious “vig” of the Mafia.

But then someone invented the notion of buying on credit from largely unlicensed brokers. You could live the dream – television, white goods, carpets, furnishings, a car – even if you couldn’t afford it and you didn’t have to go through any kind of procedure to qualify. Of course, you ended up paying two or three times the original price but the payments were spread over years so, theoretically at least, affordable. These days, credit cards lure people into the ease of purchasing and giving no thought to repayment. You don’t have to repay at all – or only a very small fraction – if you don’t mind your debt accruing exponentially.

In Britain it was called “hire purchase” or more colloquially the “never-never.” Nobody was called to account for selling goods to people who were inherently unable to afford it, were clearly incapable of managing money or, just as likely, were apt to get carried away.

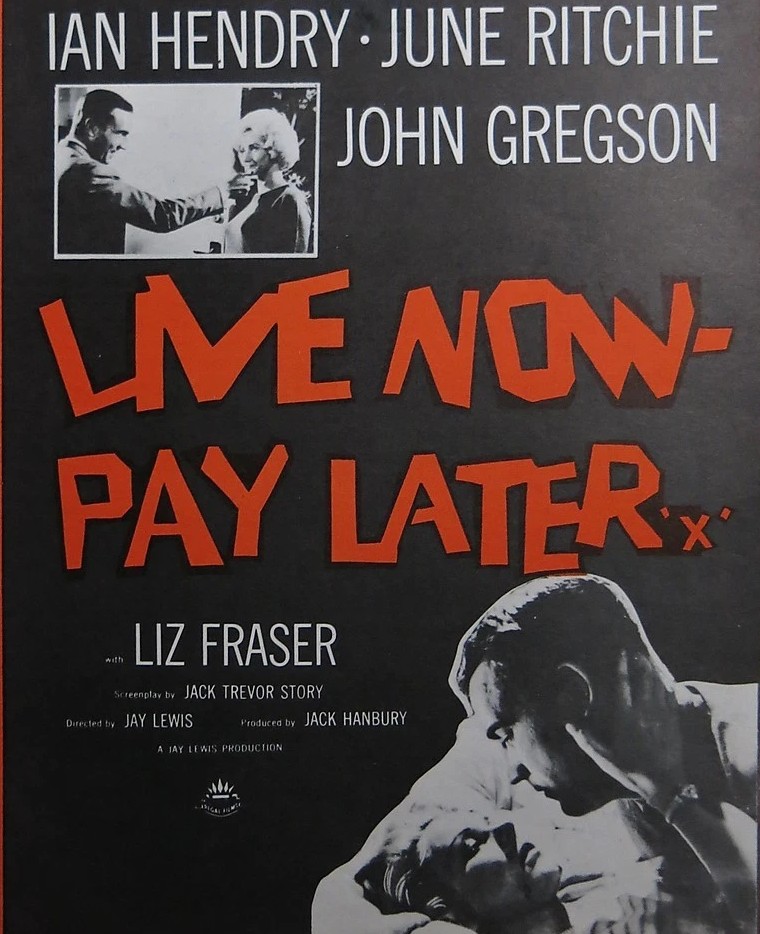

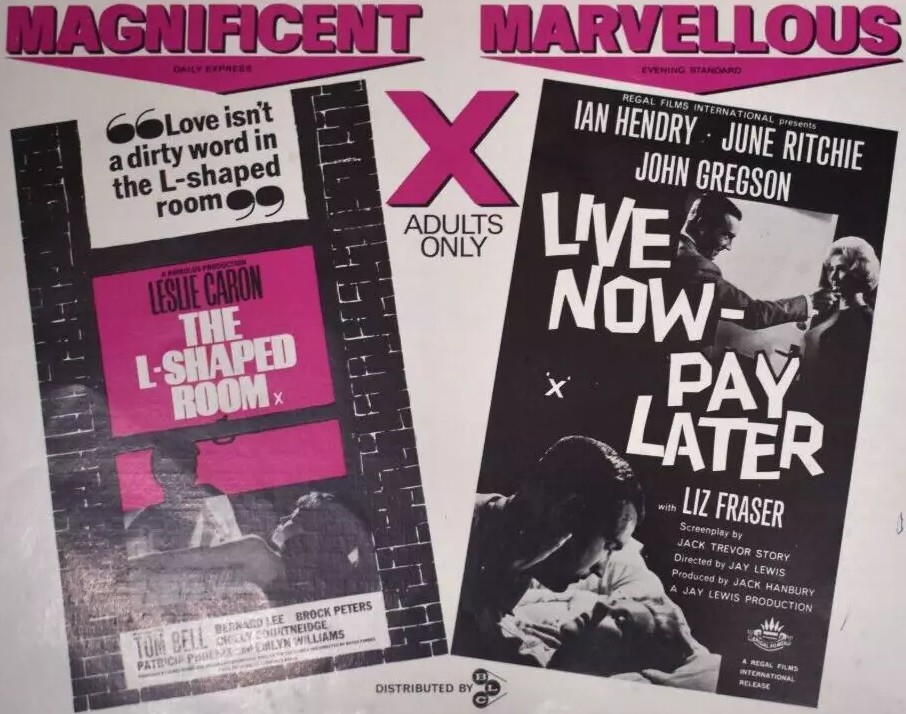

While on the one hand this is one of the saddest movies you’ll ever see, lives crushed by debt, the tone is so mixed the reality gets lost in the characterization of the kind of chancer who would later be epitomized by the likes of Alfie (1965). But whereas the Michael Caine character has oodles of charm and eventually comes good, here equally charming ace salesman Albert (Ian Hendry) never sees the error of his ways.

One of the dichotomies of the tale is that despite his earnings and his financial wheezes on the side Albert never has enough money to fund his lifestyle – snazzy sports car, great clothes – and lives in a squalid flat while ostensibly living the dream, string of women on the side. Like Werner Von Braun (I Aim at the Stars, 1960), he can’t face up to consequence much less take responsibility for his actions. But he’s not the only one using easy credit as a means of moving up in society, his boss Callendar (John Gregson) has taken up golf with a view to rubbing shoulders with estate agent Corby (Geoffrey Keen), whom he views as rising middle class without being aware that Corby also has unsustainable delusions of grandeur, hosting dinner parties for local politicians, ensuring his house is filled with desirable items.

Without doubt Albert is a superb salesman, adept at not only overcoming initial customer reluctance but persuading them to invest in far more than they ever dreamed. He is so good that his boss is more than willing to overlook his various pieces of chicanery.

But too often the comedy gets in the way. The idea that Albert can weasel his way out of any difficult situation – twice he dupes the man coming to repossess a car on which he has evaded payments for years – take advantage in unscrupulous fashion of any opportunity (he takes over an empty flat, steals the orders of rivals) and even offers advice on how to outwit, legally, bailiffs, sets him up as the kind of character (the little guy) who can defeat authority. But cheap laughs come at the expense of more serious purpose.

He leaves a trail of destroyed lives in his wake. He abandons his illegitimate daughter, fruit of a supposed long-term fling with Treasure (June Ritchie). One of his many married lovers, Joyce (Liz Fraser), wife of Corby, commits suicide – and he then proceeds to blackmail the husband. Albert’s boss is on the verge of losing out to a bigger rival.

For women, he is at his most dangerous when being kicked out, at his most persuasive and charming when trying to weasel his way in. He always finds some new woman and generally has a few on the go at the one time. The only time he appears to have any standards is when he walks away from one lover on discovering that her husband is a scoutmaster and therefore the seduction has required little skill.

But all Albert’s charm can’t disguise the brutality of debt. The arrival of the bailiffs strikes terror in hearts. A dream can turn to dust in an instant. Consequent shame unbearable. And there are no shortage of characters pointing out to Albert how heinous his actions are.

Ian Hendry (The Hill, 1965) captures the smooth-talking salesman. June Ritchie (The World Ten Times Over, 1963) has a meaty role as does Liz Fraser (The Family Way, 1966). John Gregson (The Frightened City, 1961) is unrecognizable while Geoffrey Keen (Born Free, 1966) essays the kind of grasping businessman that would become his forte. Nyree Dawn Porter (The Forsyte Saga, 1967) has a small part.

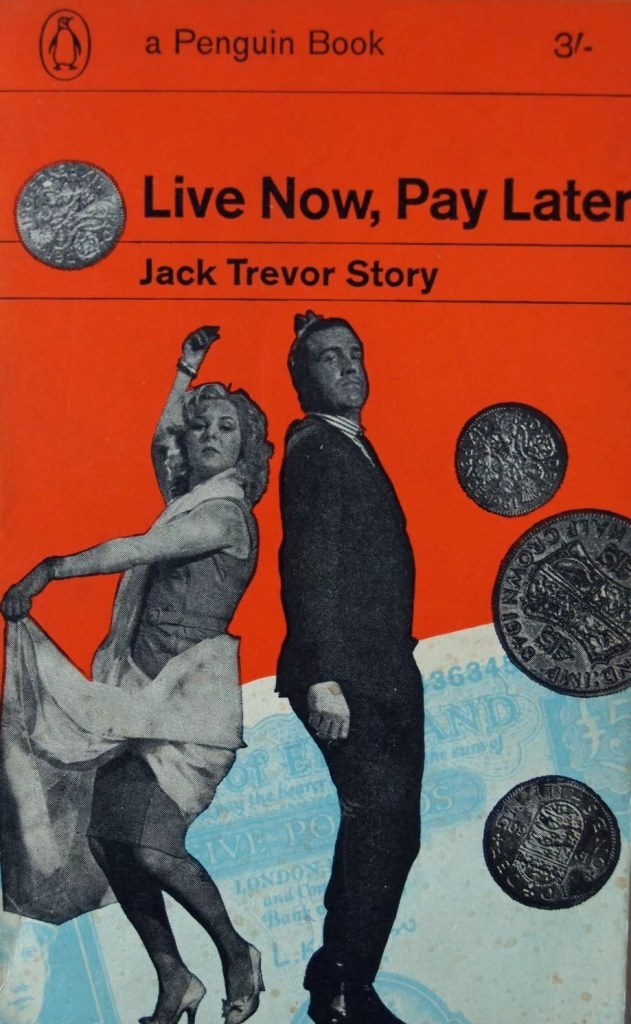

Directed somewhat unevenly by Jay Lewis (A Home of Your Own, 1964) from a script by Jack Trevor Story based on the bestseller by Jack Lindsay.

Prophetic.