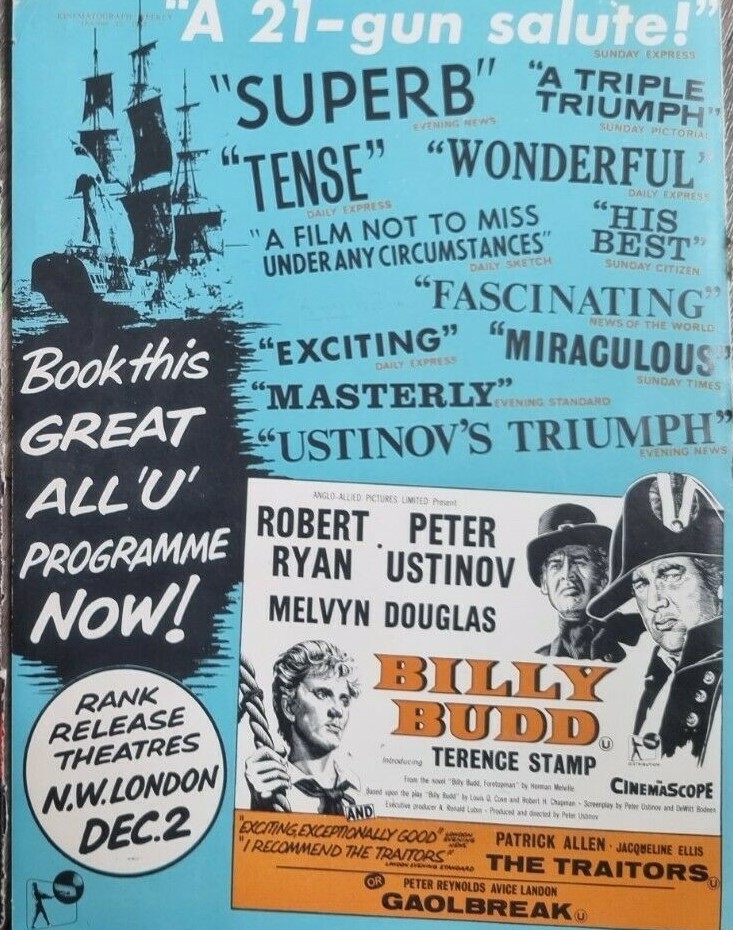

Unfairly muscled out by lavish roadshow Mutiny on the Bounty (1962) but covering similar territory minus sailors going off-piste on a South Pacific island. Peter Ustinov outranked fellow triple hyphenates Billy Wilder (writer, producer, director) and John Wayne (actor, producer, director) in that he could add acting to his other skills (writer, producer, director) and in some respects he was actually better remembered as a noted raconteur on late night television shows. I was surprised to discover he was actually well versed in the directing malarkey by the time he came to helm Billy Budd, four previous excursions dating from the late 1940s and most recently Romanoff and Juliet (1961). He was better known at this point as an Oscar-winner for Spartacus (1960). He would win another for Topkapi (1964) and go on to direct another three pictures.

Billy Budd is a claustrophic affair that you’ll need a bit of a history lesson to understand. The British Navy had two methods of recruiting sailors. The first was the more honest, awaiting a supply of volunteers. The second, the most dodgy legal proces ever invented, involved grabbing any likely candidate and forcing – “pressing”- them into service. Normally, this caper took place on land and gangs of recruitment officers did the business, hence the term “press gang.”

However, I was unaware that in times of war – this is set during the Napoleonic War – the British Navy could board any passing merchant vessel and commandeer any of its crew. In this case, Captain (actually Post Captain if you’re being technical about it) Vere (Peter Ustinov) hijacks only one sailor, Billy Budd (Terence Stamp).

Quite why it’s only this singleton is never explained. There are a couple of other irregularities that run against making this a tight ship in terms of narrative construction. The first is, that in the first of two critical incidents, our otherwise charming and chatty Budd is suddenly struck dumb with a stammer, the first time such an affliction has put in an appearance. The second is that, in consequence, Budd strikes an officer, the bullying Master-at-Arms Claggart (Robert Ryan) who hits his head while falling and dies.

Now even I know, and I’m hardly a naval scholar, that striking an officer is punishable by death. The fact that Claggart has a Capt Bligh disposition, inclined to find any opportunity to bring out the lash, makes no difference to the outcome. So while it seems that court martial provides dramatic scope, here the outcome is never in doubt. This isn’t Queeg on The Caine Mutiny, which is a more complicated affair, where the captain’s sanity is questioned.

So where the narrative should have built up in intensity, it largely flounders and depends (successfully as it happens) on audience appreciation of Budd as an innocent abroad.

That said, like Mutiny on the Bounty, it reveals the remarkable lack of recourse to any higher authority on ship should the highest authority either carry out or endorse cruelty. The minute he’s on the ship Budd is exposed to the sadistic will of Claggart who has condemned a sailor to a pitiless flogging for reasons that cannot be explained. Budd soon learns that Claggart has accomplices who will sabotage a crew member’s gear so that he will be put on a report, accumulation of sufficient black marks resulting in automatic flogging without interference from the captain.

While Vere is hardly in the Capt Bligh category and most of the time comes across as relatively amiable, our introduction to him is firing a shot across the bows of a merchant ship that doesn’t want to stop in case its crew is press ganged. He is quite ready to invoke the rules to get what he wants and is enough of a disciplinarian that the crew kowtow to him. He might feel a touch of remorse that Budd is the sacrificial lamb to the Royal Navy’s rule of law, but he’s hardly going to go against procedure.

So mostly what we’ve got is the acting. Terence Stamp (The Collector, 1965), in his debut, was Oscar-nominated and you can see why and in some senses this is the career-defining role before acting affectations and mannerisms took over. Robert Ryan (The Wild Bunch, 1969) is very effective as the sinister Claggart. And there are a host of other British names to look out for – David McCallum (Sol Madrid/The Heroin Gang 1968), Ray McAnally (Fear Is the Key, 1972), Paul Rogers (Three into Two Won’t Go, 1969) and Niall McGinnis (The Viking Queen, 1967) among the foremost.

Ably directed by Ustinov who wrote the screenplay with Dewitt Bodeen (Cat People, 1942) based on the original Herman Melville novel and a stage adaptation by Louis O. Coxe and Robert H. Chapman.

Worth seeing for Stamp’s performance.