Sometimes there’s nothing more satisfying than a well-plotted narrative that doesn’t overstay its welcome and comes with a sting – or two – in the tail. And in the B-picture world we can accommodate all sorts of venal characters and even hope – or at least wonder if – they will get away with their nefarious plans.

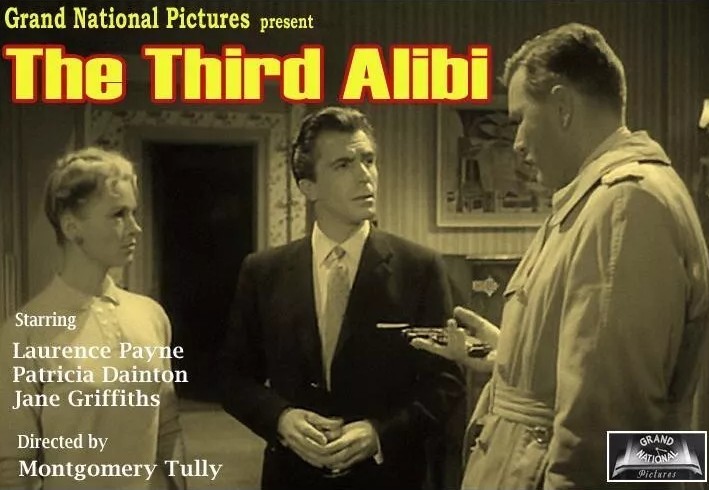

We might have sympathy for stage composer Norman (Laurence Payne) stuck in a soulless marriage with Helen (Patricia Dainton). Small wonder he seeks spice through an affair with divorced sister-in-law Peggy (Jane Griffiths). After all, being a creative is hard work and we want him to enjoy showbiz success.

But that’s until driving home at night he knocks down an old man and races off without stopping. Luckily, the old fella’s not dead, otherwise it would have been in the papers. But then he’s bounced into asking his wife for a divorce since Peggy has announced she’s pregnant. But Helen isn’t agreeable, not least because of her dislike for her sister. And Helen’s very ill, a heart condition, but for reasons best known to herself, won’t confide this to her husband.

So Norman is left with no alternative but to bump her off. He comes up with a very clever plan that will allow him to pretend not be at home when he kills his wife there and also dreams up one of these clever alibis for Peggy, who’s integral to his plan, by getting her to make a nuisance of herself at the cinema, so everyone recalls her both arriving and departing, allowing her to slip out of the theater for the period of time she needs to assist Norman.

But Helen overhears the conspiracy. And when Norman goes home to shoot his wife, using an unlicensed therefore untraceable pistol provided by Peggy (war heirloom) instead of his own licensed traceable gun, he discovers the house is empty.

When he returns to his lover, he finds her dead, shot through the head. As he rushes out, the police arrive. He’s only a suspect for a short time as his various alibis hold up. Helen appears to be standing by him. But then the police find his gun in the bushes outside the dead woman’s house.

When Helen confesses to the police that her husband has demanded a divorce, that puts her in the firing line. Except she’s got a perfect alibi. She stole the idea from the conspirators, making her visit to the cinema easily remembered by the staff both at the start of the movie and the end. It’s pretty much an unbreakable alibi unless any other witness can finger her.

Norman protests his innocence of course. And the irony is we know he’s innocent, but our sympathies are now with the killer, Helen, which twists around our preconceptions.

After all, not only is she the injured party in the romantic stakes, but she’s very ill, so needs all the audience sympathy she can get. So the audience, against its better judgement, is batting for her.

But, suddenly, twist number one, they don’t have to. Because the strain is all too much, and she has a heart attack and drops dead. And, surely, it won’t be long before Norman can find a way out of his predicament. And he believes he has the very thing.

There’s a nosy old neighbor who takes too close an interest in visitors to the house. So he must have seen Norman arrive there at the very time his lover was shot. The neighbor is brought in.

He’s a poor old soul. And blind. The result of being knocked over by a car a few weeks before.

What a cracking ending to a cracking tale. I always wonder why these kind of stories don’t get resurrected for some sort of portmanteau series, in the manner of Tales of the Unexpected. Although there’s little fat on them, a bit of judicious trimming would make them ideal for a one-hour television slot and this one, in particular, is little more than a three-hander, so wouldn’t cost much.

Each of the main characters is well drawn, each allowed a moment to stretch their emotional muscles. Solid, if not spectacular, acting from Laurence Payne (Crosstrap, 1962), Patricia Dainton (The House in Marsh Road, 1960), and Jane Griffiths (The Double, 1963), and impressive turn from John Arnatt (A Challenge for Robin Hood, 1967) as a doughty cop.

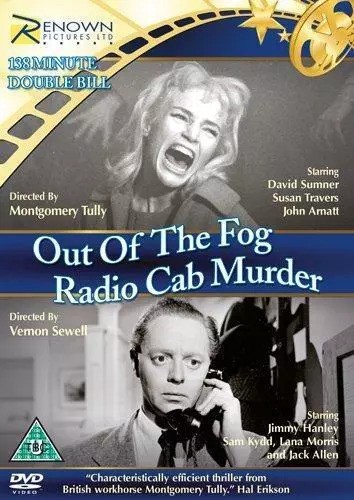

Written by Maurice J. Wilson (The House in Marsh Road) and director Montgomery Tully (The House in Marsh Road) from a play by Pip and Jane Baker. Tully is in fine form at the helm, wasting no time in driving this towards ironic conclusion.

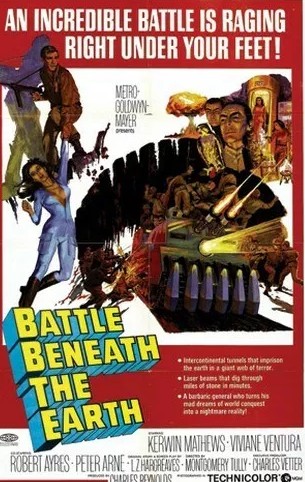

I’ve been clocking up a few from the Tully portfolio in the last month or so. Astonished to find he directed another seven pictures this decade, so I might, in due course, complete the collection.

Enjoyable.