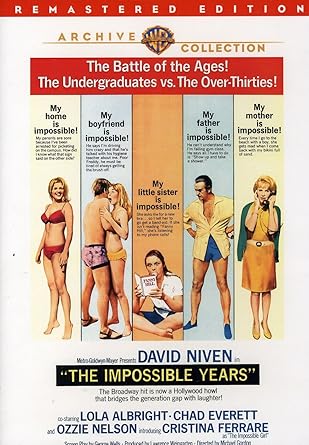

Generation gap comedy driven by unmentionables and the prospect of perplexed father getting more pop-eyed by the minute. By default, probably the last bastion of morality before censorship walls – the U.S. Production Code eliminated the following year – came tumbling down and Hollywood was engulfed in an anything goes mentality. Denial enters its final phase, quite astonishing the mileage achieved by not letting the audience in on what’s actually going on.

Psychiatrist lecturer Jonathan (David Niven) finds his chances of promotion potentially scuppered after lissom teenage daughter Linda (Christine Ferrare) is arrested at a demonstration carrying a banner bearing an unmentionable word. That brings to the boil the notion that Linda may not be quite so sweet as she appears, Jonathan previously willing to overlook minor misdemeanors like smoking and speeding. But it turns out Linda may also have lost her virginity, that word also verboten, and may even be, worse, illegally married.

So the question, beyond just how manic her parents can be driven, is which male is her lover: the main candidates being a trumpet-blowing teenage neighbor and let) or laid-back artist hippie who has painted her in the nude.

Innuendo used to be the copyright of the Brits, in the endlessly smutty Carry On, series, but here the number of words or phrases that can be substituted for “sex” or “virgin” must be approaching a world record, but delivered with gentle obfuscation far removed from the leering approach of the Brits.

It’s a shame this movie appeared in the wake of bolder The Graduate (1967) because it was certainly set in a gentler period and its tone has more in common with Father of the Bride (1950). Setting aside that most of the adults, for fear of offending each other, can’t ever say what they mean, the actual business of a young woman growing up and demanding freedom without ostracising her parents is well done, Linda stuck in the quandary of either being too young or too old to move on in her life.

The scenes where that issue is confronted provide more dramatic and comedic meat than those where everyone is grasping, or gasping like fish, for words that mean the same as the other words they refuse to utter.

Parental issues are complicated in that Jonathan has set himself up as an expert on dealing with the problems growing children present. He views himself as hip when, as you can imagine, to younger eyes, he’s actually square. And he’s also worried his younger daughter Abbey (Darlene Carr) will start to emulate her sibling.

Compared to today, of course, it’s all very innocent and I’m sure contemporary older viewers might pine for those more carefree times. It doesn’t work as social commentary either, given the rebellion that was in the air although it probably does accurately reflect how adults felt at confronted by children growing up too fast in a more liberal age.

David Niven (Prudence and the Pill, 1968) brings a high degree of polish to a movie that would otherwise splutter. He’s playing the equivalent of the stuffy Rock Hudson/Cary Grant role in the Doris Day comedies who always get their comeuppance from the flighty, feisty female. That fact that it’s father-and-daughter rather than mismatched lovers only adds to the fun. And there were few top-ranked Hollywood actors, outside perhaps of Spencer Tracy (Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, 1967) who audiences would be interested in seeing play a father.

The unmentionable conceit wears thin at times but Niven and Cristina Ferrare (later better known as the wife of John DeLorean) do nudge it towards a truthful relationship. Former movie hellion Lola Albright (A Cold Wind in August, 1961) is considerably more demure as the Jonathan’s wife. Chad Everett (Claudelle Inglish, 1961) breezes in and out.

Although at times giving off a “beach party” vibe, it manages to examine the mores of the time.

Director Michael Gordon has moved from outwitted controlling mother (For Love or Money, 1963) to undone controlling father without dropping the ball. It’s based on the Broadway play of the same name by Robert Fisher and Arthur Marx.

Lightweight for sure but worth it for David Niven and the sultry Ferrare.