Unusually nuanced thriller. Unusually lean, too, barely passing the 90-minute mark. There’s a Hitchcockian appreciation of the danger lurking in wide open spaces. And the background is the Middle America of annual fairs, marching bands, pie-eating competitions, rural pride in farming and marksmanship.

But there’s an undercurrent that will strike a contemporary audience. The contempt of big business for its customers. The sex trafficking, too, will sound an all-too-common note especially as the young women come from an orphanage set in the heart of homespun America in what appears to be a streamlined service.

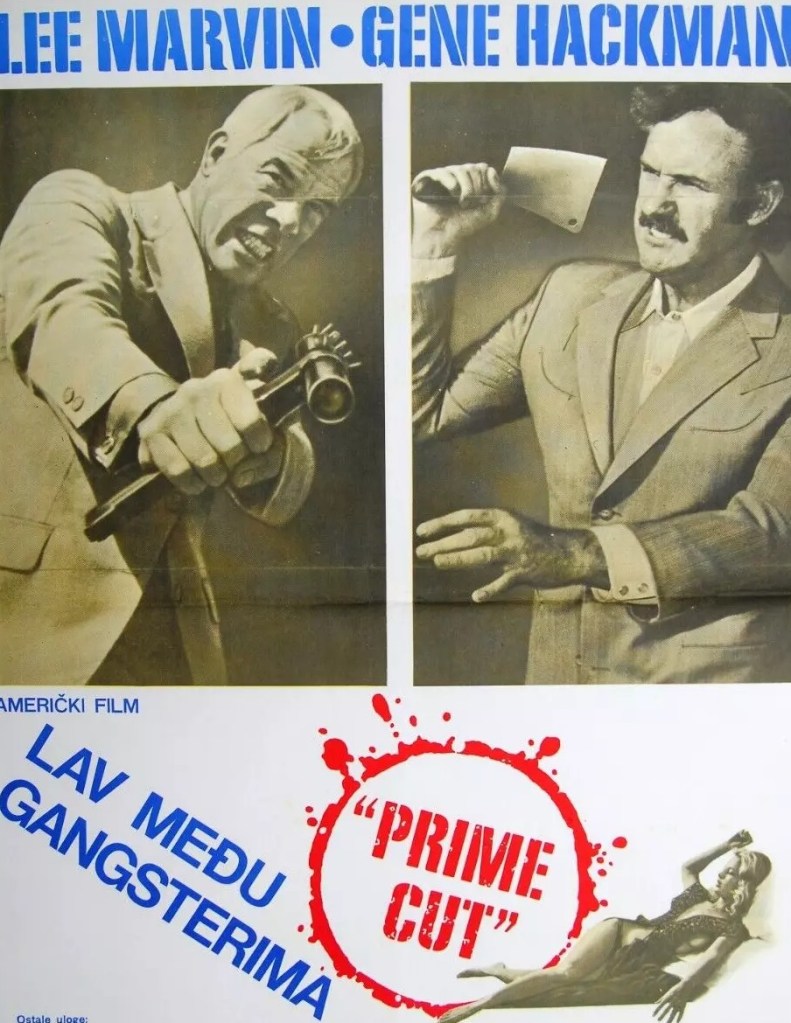

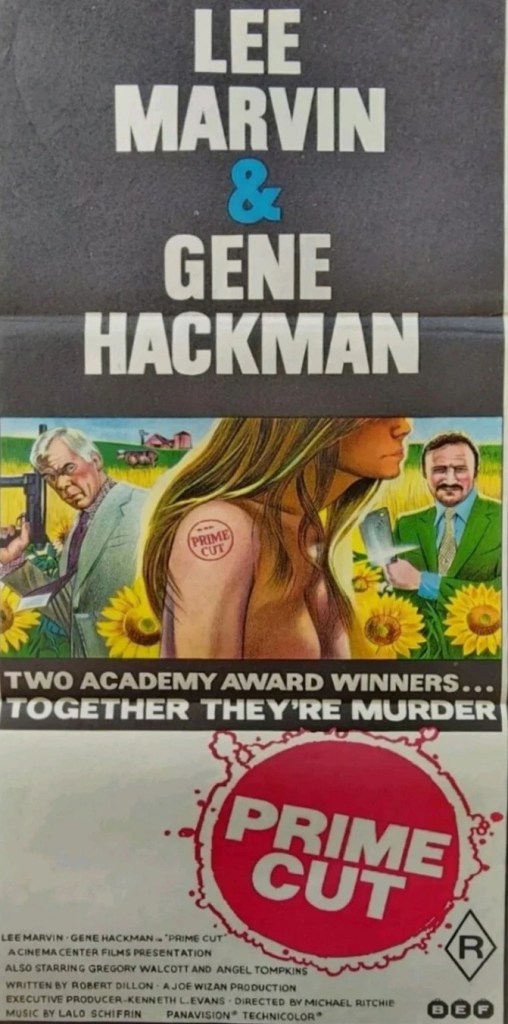

We shouldn’t at all take to hitman Nick (Lee Marvin) except that he’s got a code of honor and sparing with words. He’s been sent from Chicago to Kansas to sort out with what would later be termed “extreme prejudice” Mafia boss and meat-packer Mary Ann (Gene Hackman) who’s been skimming off the top. As back-up Nick is handed a trio of young gunslingers anxious to prove themselves while his faithful chauffeur owes Nick his life.

Mary Ann doesn’t just have a factory, he has a fort, a posse of shotgun-wielding henchman standing guard. So Nick has to plunge right in and confront the miscreant. As well as dealing with animal flesh, Mary Ann has a side hustle in sex trafficking, displaying naked women in the same straw-covered pens as his beef.

Responding to a whispered “help me” by Poppy (Sissy Spacek) Nick buys her freedom, but Mary Ann isn’t for knuckling down to the high-ups in Chicago and since he’s already despatched a handful of other hoods sent on a similar mission as Nick he’s intent on turning the tables.

The action, when it comes, is remarkably low-key and all the more effective for it. Swap a crop duster for a combine harvester and the head-high prairie corn for the usual city back streets and you realize someone has dreamed up a quite original twist on the standard thriller. No need for a car chase here to elevate tension, it’s already a quite efficient slow burn.

This could be an ode to machinery. The entire credit sequence is devoted to the way machines chew up cow flesh and turn it into strings of sausages and the like. The combine harvester chews up and spits out an entire automobile, grinding the metal through its maw. And then there’s the machinery of business, the ability, at whatever cost, to give the public what it wants, in whatever kind of flesh takes its fancy.

You’ll remember the combine harvester sequence and the shootout in the cornfields, but you will come away with much more than that. Remember I mentioned nuance. Sure Mary Ann is an arrogant gangster and you’d think with hardly an ounce of humanity, but that’s until you witness his relationship with his simple-minded brother Weenie (Gregory Walcott). That could as easily have fallen into the trap of cliché sentimentality. Instead, there’s roughhouse play between the pair and it’s all the more touching for being realistic.

There’s a tiny scene where one of the young hoods asks Nick to meet his mother, in the way of a young employee wanting to show off that he was working for a top man. And Nick also goes out of his way to praise what’s on offer at the fair from a couple of women anxious for praise.

One of the tests of a good actor is what they do when they enter an unfamiliar room. Your instinct and mine, like ordinary people, would be to look around not just lock eyes on the person you’ve come to meet. So when Poppy wakes up in a luxurious hotel room she doesn’t go into all that eye-rubbing nonsense, but instead marvels at her surroundings. And although she hangs on his every word – and his arm – Nick isn’t in the seduction business, instead spoiling the young woman with expensive clothes.

There are several other scenes elevated just by touches. The credit sequence ends with a shoe appearing among the meat being processed – Mary Ann’s victims don’t sleep with the fishes but with the sausages. Poppy recalls a childhood spent in a rural wonderland, squirrels, rabbits, the splendors of nature, and reveals a lesbian relationship with another orphan Violet that is the most innocent description of love and sexual exploration you’ll ever hear.

Violet is the victim of multiple rapists. Weenie has passed her onto a bunch of down-and-outs for the price of a nickel. When Nick unclenches her clenched fist you’ll be horrified to see how many nickels tumble out.

Lee Marvin (Point Blank, 1967) is at his laconic best and Sissy Spacek (Carrie, 1976) makes a notable debut but Gene Hackman (Downhill Racer, 1969) overplays his hand.

Director Michael Ritchie (Downhill Racer) was on a roll, following this with The Candidate (1972), Smile (1975), The Bad News Bears (1976) and Semi-Tough (1977) before the execrable The Island (1980) badly damaged his career.

Written by Robert Dillon (The French Connection II, 1975).

Well worth a look.