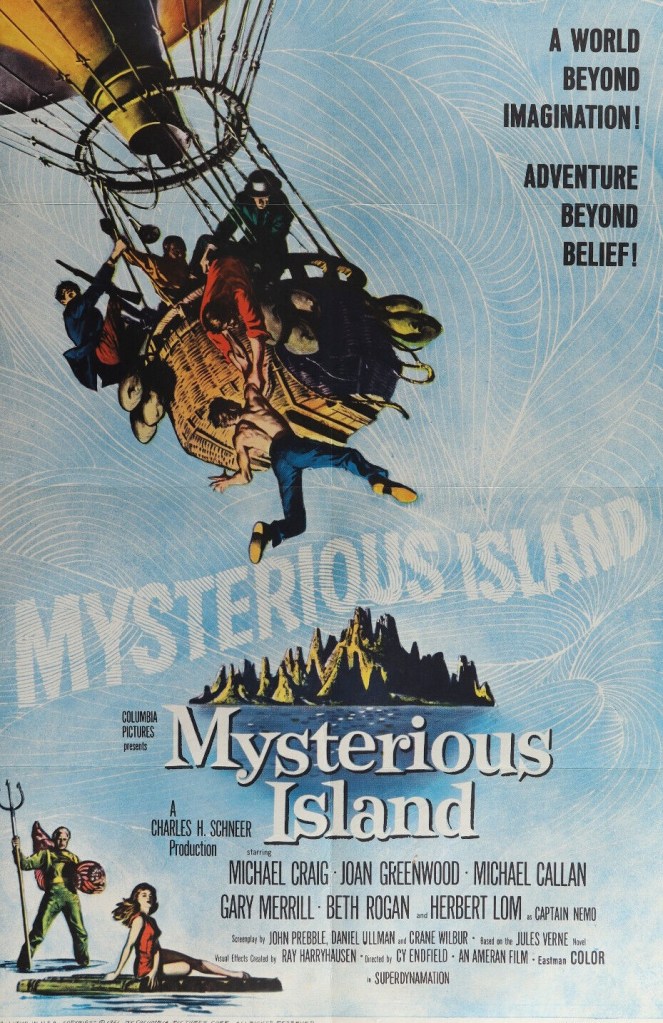

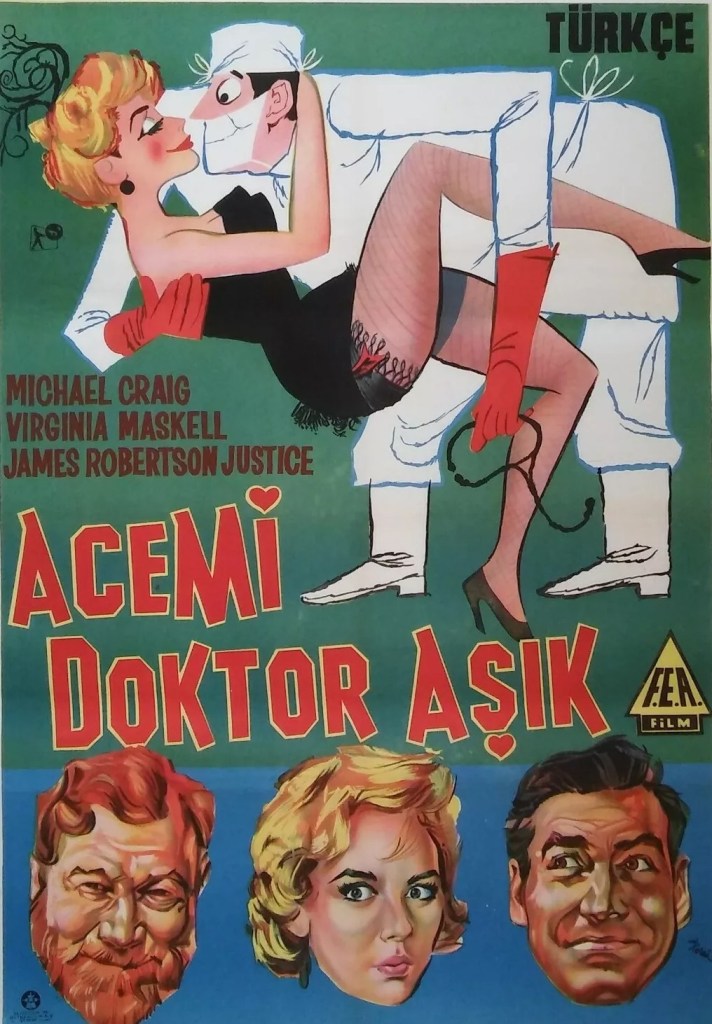

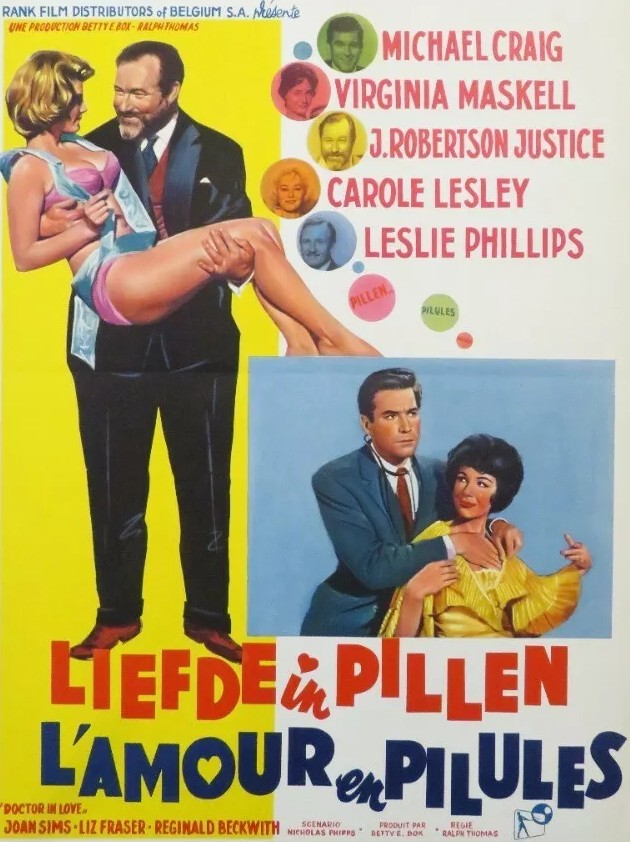

Chortled all the way through. You can see why it was the biggest film at the British box office in 1960. Dirk Bogarde had turned up his nose at repeating the character for the fourth time and went off to make more serious pictures like Victim (1961) which, it transpired, dented his box office appeal. Replacement Michael Craig (Mysterious Island, 1961), while brawnier, passes this particular screen test with flying colors though he has his work cut out to hold his own against such practised scene stealers as James Robertson Justice (Mayerling, 1968) and Leslie Phillips (The Fast Lady, 1962) and once Virginia Maskell (The Wild and the Willing, 1962) enters proceeding her coolness makes the camera her own.

I was surprised how much this relied on innuendo. But this is a gentler exercise in smut than the sniggering guffawing Carry On approach. And there’s little chance of it descending into misogyny since the females hold all the aces. The plot is episodic and none the worse for that and even a diversion into a strip club, which might suggest a narrative clutching at straws, proves a surprising highpoint.

Basic story shifts Dr Hare (Michael Craig) out of hospital and into general practice which provides ample comedic opportunity via patients and colleagues. But, first of all, just to confuse matters and as if the producers were worried the series might not survive outside the boundaries of St Swithins Hospital, the tale begins with him returning to hospital with what turns out to be jaundice.

Cue the booming interventions of Sir Lancelot Spratt (James Robertson Justice) and the first of the love stories wherein Hare and Dr Hinxman (Nicholas Parsons) are rivals for flighty Nurse Sally Nightingale (Moira Redmond), who, in the first of many knocks to the male ego, while playing off one against the other goes off with another man. Before she does, Dr Hinxman takes revenge by prescribing all sorts of medications which will leave Hare so indisposed he is unable to respond to the nurse’s ardor.

Back in civvy street, as a GP, Dr Hare has to fend off predatory female patients and secretary Kitten Strudwick (Carole Lesley) and deal with standard comedic issues such as the boy who gets his head jammed in a cooking pot and the less common task of explaining the facts of life to a 40-year-old virgin. His boss Dr Cardew (Nicholas Phipps) is under the thumb of a wife who has shipped out to California only to summon her husband every now and then. The ever-amorous Dr Burke (Leslie Phillips) fills in and is the prime mover in an episode that involves strippers Dawn (Joan Sims) and Leonora (Liz Fraser). There’s a particularly good reversal in a drunken scene where the totally inebriated Wildewinde (Reginal Beckwith) completes all the police drunk tests (if that’s what they’re called) with ease.

When Dr Burke is incapacitated, his place is taken by Dr Nicola Barrington (Moira Redmond). And that should have been enough of a plot to see the picture through but the movie doubles down on complication. Dr Barrington fends off Dr Hare and when Nurse Nightingale reappears Barrington in due course quits. Dr Spratt is also on board for further scene-stealing duties including ruling the roost in a strip club and undergoing an operation.

The romantic situation is resolved, Dr Spratt is put in his place temporarily and our hero effects a return to the hospital.

I wouldn’t say the writing (by Nicholas Phipps) is of the highest caliber but the jokes come at an assembly line pace and the cast are superb, barely a cast member incapable of stealing a scene. You hire James Robertson Justice and Leslie Phillips at your peril. Without Dirk Bogarde hogging the scenery, this flows much better than others in the series, with the supporting cast being more than just foil to a star who was a major box office attraction at the time. And it helps that the women – Moira Redmond (Nightmare, 1964), Virginia Maskell, Carole Lesley (Three on a Spree, 1961), and Carry On regulars Joan Sims and Liz Fraser – are even more adept at scene-stealing than the men and not merely foil for misogynist jokes as in the Carry On series.

Director Ralph Thomas (The Wild and the Willing) seems to have found a new lease of life without having to deal with Dirk Bogarde and brings a certain verve to proceedings, especially in tripping up male ego.

Comedy is such an odd one to judge. Many a time I have sat through with scarcely a titter movies I’ve been told are hilarious. Other times I’ve been told to give them a free ride because they are making a point. So I stick to my own rule.

Make me laugh – I don’t care how – and this had me laughing all the way through.