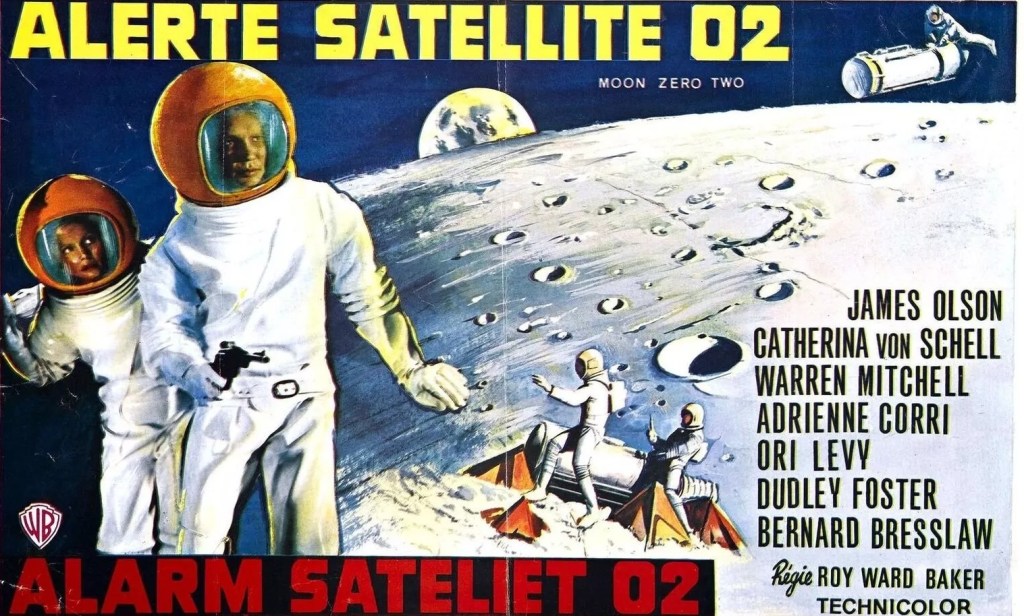

Not much that’s redeemable from this British sci fi effort. Maybe the idea of the “dirty universe” clogged up by waste with salvage hunters retrieving bits of old satellites and space objects. Or maybe an early version of “unobtainium,” the rare mineral that’s going to make someone very rich, in this a solid block of sapphire and some mined nickel. Or maybe the colonizing of the Moon for gain rather than the advance of science.

But that’s about it. Takes about 30 minutes for a story to emerge, the rest of the time taken up with info dumps and character background, so we know that ace pilot Bill (James Olson) was the first man on Mars and wants to repeat the same feat for Mercury, Jupiter and other distant planets and would rather become a salvager than lower himself to become a passenger pilot. His girlfriend Liz (Adrienne Corri) is an officious official and threatens him with being grounded on safety grounds.

But that kind of bureaucracy is par for the course in British sci fi which liked to clutter up the narrative with accountants (The Terronauts, 1967, et al) and various levels of officialdom. And there’s another British trope. Take a well-known comedian and turn him into an unlikely tough guy of sorts – Eric Sykes as an assassin in The Liquidator (1965) would be in pole position but Carry On regular Bernard Bresslaw runs him close here as a gun-toting bodyguard.

Or maybe the Brits just like a hybrid. Stick some comedy into sci fi. Certainly the animated credits suggest this is going to major on comedy, which turns out not to be the case unless you were laughing at how inept the whole project is.

Especially when director Roy Ward Baker simply resorts to slo-mo to suggest loss of gravity in space. And when the space outfits look as if they were run up by someone’s ancient auntie. Just to show the bad guy is a bad guy, entrepreneur J.J. Hubbard (Warren Mitchell) wears a monocle. He hires Mike to go find the sapphire asteroid and bring it back to the Moon, where it can be dumped on the “far side”, well away from any nosey parkers, to make it look as if it had landed there on its own, thus bypassing Space Law.

But Mike’s already made the acquaintance of Clem Taplin (Catherine Schell) who’s hiked up from earth to search for missing geologist brother and once Mike’s located the sapphire he heads out into the far side of the Moon to find the brother. They find him all right but by this point he’s just a skeleton though he has uncovered nickel deposits. He’s been killed by Hubbard and the couple are ambushed and have to shoot their way out (the efficacy of bullets in space in never explained) in a manner that suggests, as the posters liked to proclaim, a “space western.”

Mike gets his revenge by stranding all the bad guys he hasn’t already killed on the sapphire in space.

It would have probably been okay if any of the actors had shown any screen spark. But they’re all lumpen, although perhaps you can blame the restraints of the space costumes, or maybe even just the script. Oddly enough James Olsen would make his mark in sci fi adventure The Andromeda Strain two years later, but that had both better direction (by Robert Wise) and a more intriguing script (from Michael Crichton).

You might as well have wrapped up Catherine Schell (On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, 1969) in cotton wool for all the impact she was able to make. Warren Mitchell (The Assassination Bureau, 1969) looks as if he’s desperately trying to stifle a grin.

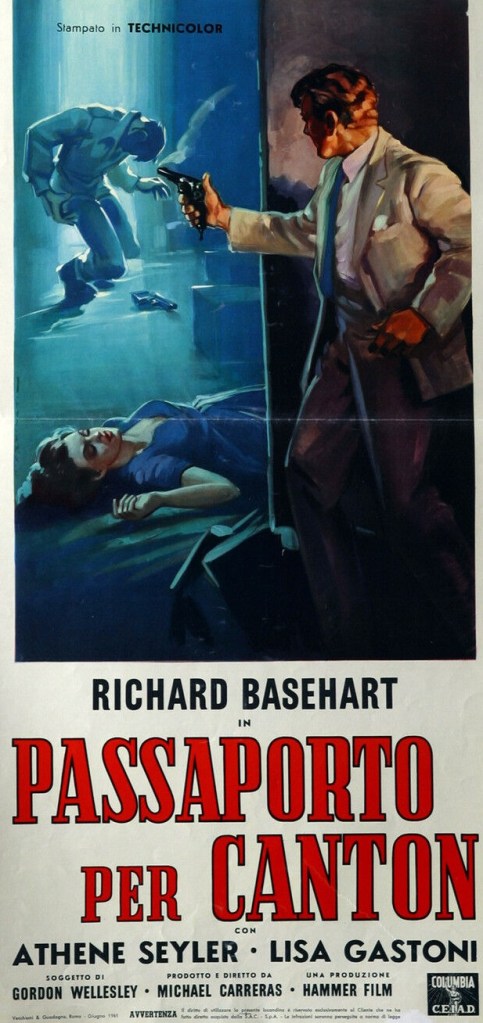

Hammer boss Michael Carreras (The Lost Continent, 1968) wrote the screenplay, and produced, so he should at least share the blame with Roy Ward Baker (Quatermass and the Pit, 1967).