Adaptations of sprawling novels require a firm hand at screenplay stage. Exodus (1960), for example, excised the first couple of hundred pages depicting the first two millennia relating the history of the Jews in the Leon Uris bestseller. Hawaii (1966) sliced the James Michener epic in two, the sequel The Hawaiians (1970) taking up the slack. Otherwise, like here, you end up with a multi-generational sprawl.

The producers clearly felt that the endzone – two grandfathers warring over a grand-daughter that was also somehow a metaphor for the battle for Alaskan statehood – was too good to miss. Except author Edna Ferber (Giant, 1956) had already dealt with that problem, in her book beginning at the end, where feminist icon Christine Storm is given a voice and the story unfolds in flashback. Instead, it’s Christine who has to wait ages to make an appearance and scarcely in the manner outlined by the novelist.

Initially, ex-World War One soldier Zeb (Richard Burton) and Alaskan fisherman Thor (Robert Ryan) become friends after the latter saves the former from drowning, Zeb having lost his job in a cannery for fancying boss’s daughter Dorothy (Martha Hyer). The pair then decide to go into business together, Thor catching the salmon, Zeb canning them. But illicit love tears the incipient partnership apart, Thor’s fiancée Bridie (Carolyn Jones) falling for Zeb.

Finding banks are against funding a nobody, Zeb hits the mother lode in capitalizing his business by marrying the wealthy Dorothy, while a distraught Thor hits the snowy wastes and returns with an Eskimo son. Bridie hangs around long enough to sew the seeds of suspicion and take a hand in bringing up the baby, though holding back on the marriage that might seal the deal.

So then we are quickly onto the second generation. Thor’s son Einer (Barry Kelley) and Zeb’s daughter Grace (Shirley Knight) elope to the snowy wastes where, guess what, she gets pregnant, but, guess what, he is killed by a bear and she dies giving birth to Christine (Diane McBain).

So that takes us to the final act, Dorothy now also conveniently dead, grandfathers sharing custody, and the metaphor for the birth of Alaska in full swing. Zeb, now a greying ruthless industrialist who finds it easier to feed his multiple canneries by catching fish in traps as they exit the Alaskan rivers, opposes statehood, fearing legislation will curb his entrepreneurial tendencies and that, more to the point, he will be hardest hit by the taxation required to fund the government apparatus. Thor, meanwhile, has turned greying politician, fighting Zeb every inch of the way, Christine now mere collateral damage.

the date it appeared in the U.S.

It’s certainly a full-throated melodrama, and might have worked better if it had skipped a generation and got to the warring grandparents sooner, or worked the love triangle up to a higher pitch, but that might have felt like the bloodbath required to kill off Dorothy, Einer and Grace would have looked even more calculated. And it could have done with more actual high drama, fishermen battling mighty waves on the high seas, for example, as in The Perfect Storm (2000), and to be honest watching caught salmon shooting along cannery travelators is no substitute.

The other problem is that neither Richard Burton (Becket, 1964) nor Robert Ryan (The Wild Bunch, 1969) has settled into their screen persona. In the former’s case it’s the voice. Except in fleeting instances, we are deprived of his whisky-sodden sonorous tones. In the latter it’s the stillness, all the work done with the eyes or a grimace instead of an overworked marionette, body jumping, arms pumping. In both cases, and with the entire cast for that matter, there’s over-reliance on flashing eyes, a mainstay of overwrought melodrama.

If you’re searching out subtlety you’d have to watch the women, the look on Dorothy’s face on first meeting Bridie and recognizing a rival, the various expressions on Bridie’s face – for virtually the whole picture – as she observes the unobtainable Zeb grow even more distant, and Grace as she realizes she is being duped into a marriage of political convenience. And with so much story to pack in, the best scene in the picture just whizzes by, when, in the absence of the town doctor, Bridie is called upon to be midwife to Zeb’s child, knowing that it should, if only she had the courage at the time, be hers.

The Alaskan statehood element was, I imagine, lost on non-American audiences, the statehood metaphor probably lost on everyone except discerning critics, and as far as I can work out from the box office nobody anywhere gave two hoots for the picture. Bear in mind Richard Burton was far from a major star, having burned his boats after star-making roles in The Robe (1953) and Alexander the Great (1956) failed to provide the necessary glue to bind actor and moviegoer. In fact, Burton was so little in demand he was scarcely making a movie a year – and only The Robe entered positively in the box office balance sheet – until Cleopatra (1963) revived his career.

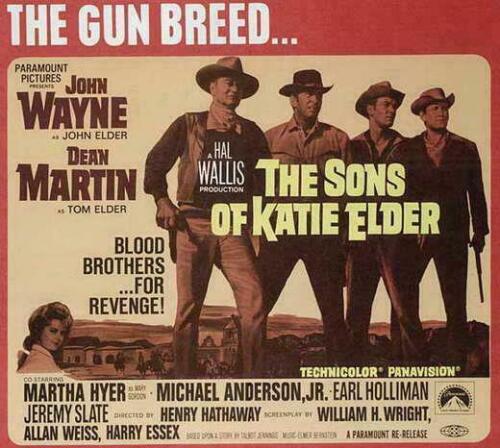

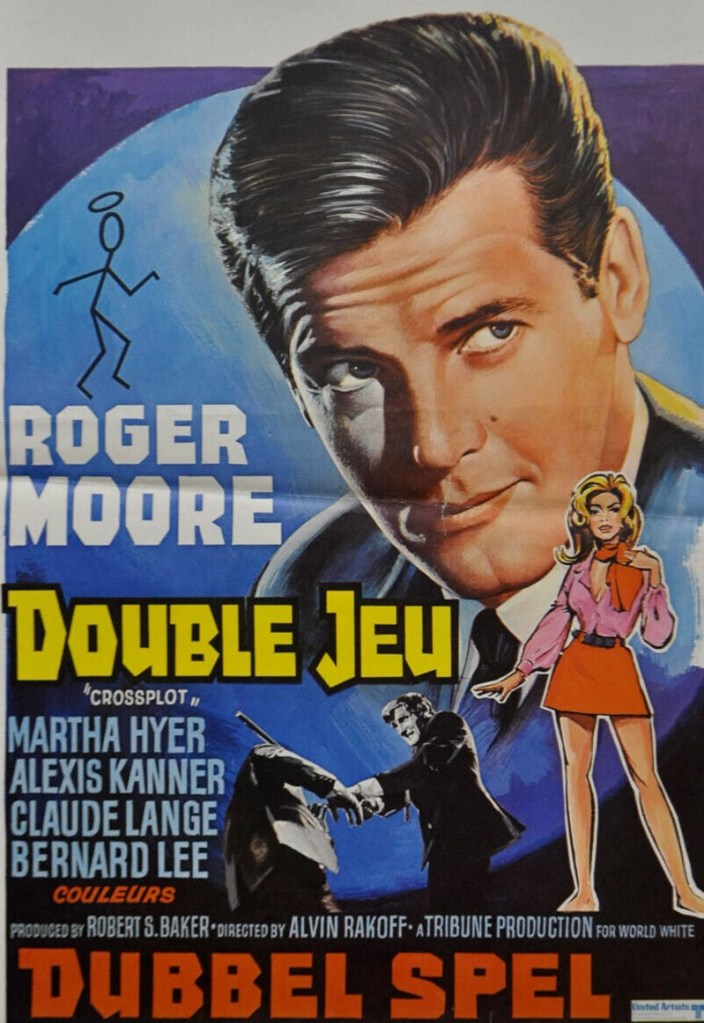

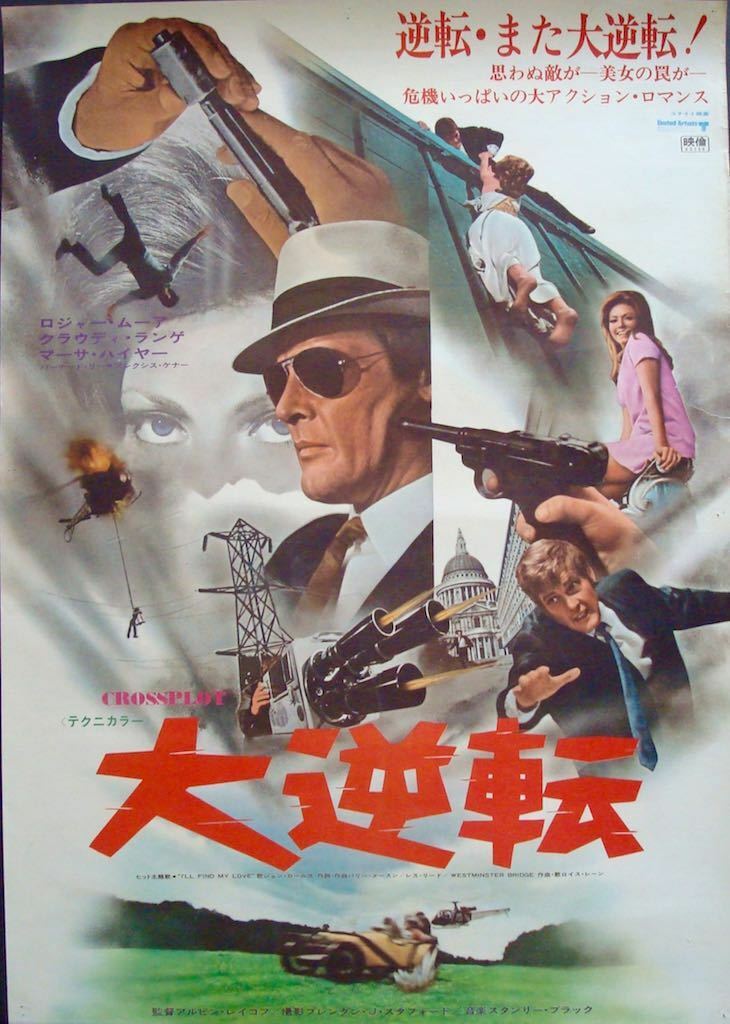

So with a cut-price Burton and an over-extended Robert Ryan there’s little the women can do to rescue the picture, though Carolyn Jones (How the West Was Won, 1962), Martha Hyer (The Sons of Katie Elder, 1965), the debuting Diane McBain (Claudelle Inglish, 1961) and Shirley Knight (The Group, 1966) put in more heartfelt performances.

Vincent Sherman (A Fever in the Blood, 1961) directed from a screenplay by Harry Kleiner (Bullitt, 1968). One look at the gem George Stevens created from Giant and all you can see here is missed opportunity.