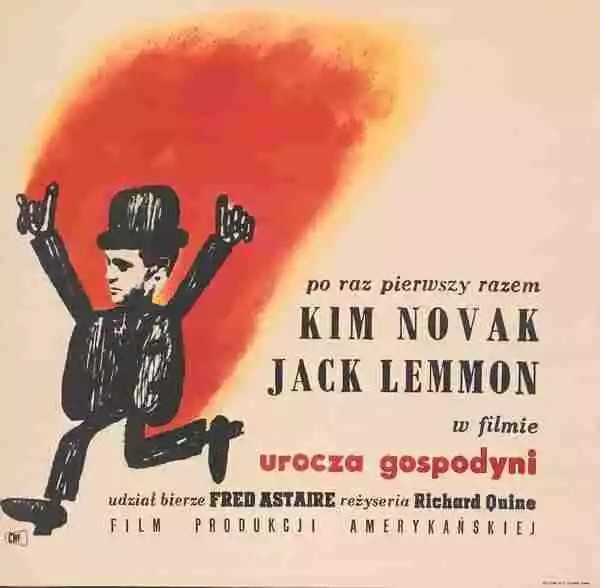

Botched job. Not an all-out stinker. Something that should easily have worked – and didn’t. Thanks to the principals involved. Biggest finger of blame points at Jack Lemmon (How To Murder Your Wife, 1965), who jitters and jabbers, arms waving, eyeballs swivelling, classic example of over-mugging the pudding.

But Kim Novak (Strangers When We Meet, 1960) is as bad for the opposite reason. She’s completely insipid. Sure, she’s meant to be playing someone frightened out of her wits but she could as easily be worrying about how to lay the table for all the energy we get.

Director Richard Quine (Strangers When We Meet) hardly gets off scot-free for allowing this to happen as well as quite bizarre shifts in tone from a fog-wreathed London straight out of Sherlock Holmes, to a denouement with Novak naked in the bath – Lemmon averts his eyes but the camera and hence the audience doesn’t – and a climax straight out of the Keystone Cops. I know Quine had a fling with Novak but it looks like he’s trying to share her physical charms with all and sundry, scarcely a scene goes by where’s she’s not in her underwear, night-time apparel, soaking wet one way or another or wearing revealing outfits. The “Notorious Cleavage” might have been a better title.

As I say, this should have worked. The story is straightforward enough, a mystery, red herrings aplenty, mysterious lurking figures, enough twists to give it edge.

Diplomat William Gridley (Jack Lemmon), newly arrived from the States, comes to view an apartment to rent in Mayfair only to find landlady Mrs Hardwicke (Kim Novak) most unwelcoming. Unfortunately for her, it’s love at first sight for him, so she can do no wrong. Which is unfortunate for him, for she is suspected of murdering her husband. That doesn’t sit well with Gridley’s boss Ambruster (Fred Astaire) who feels staff should be completely above board and not risk the good name of the U.S. by consorting with film noir style damsels.

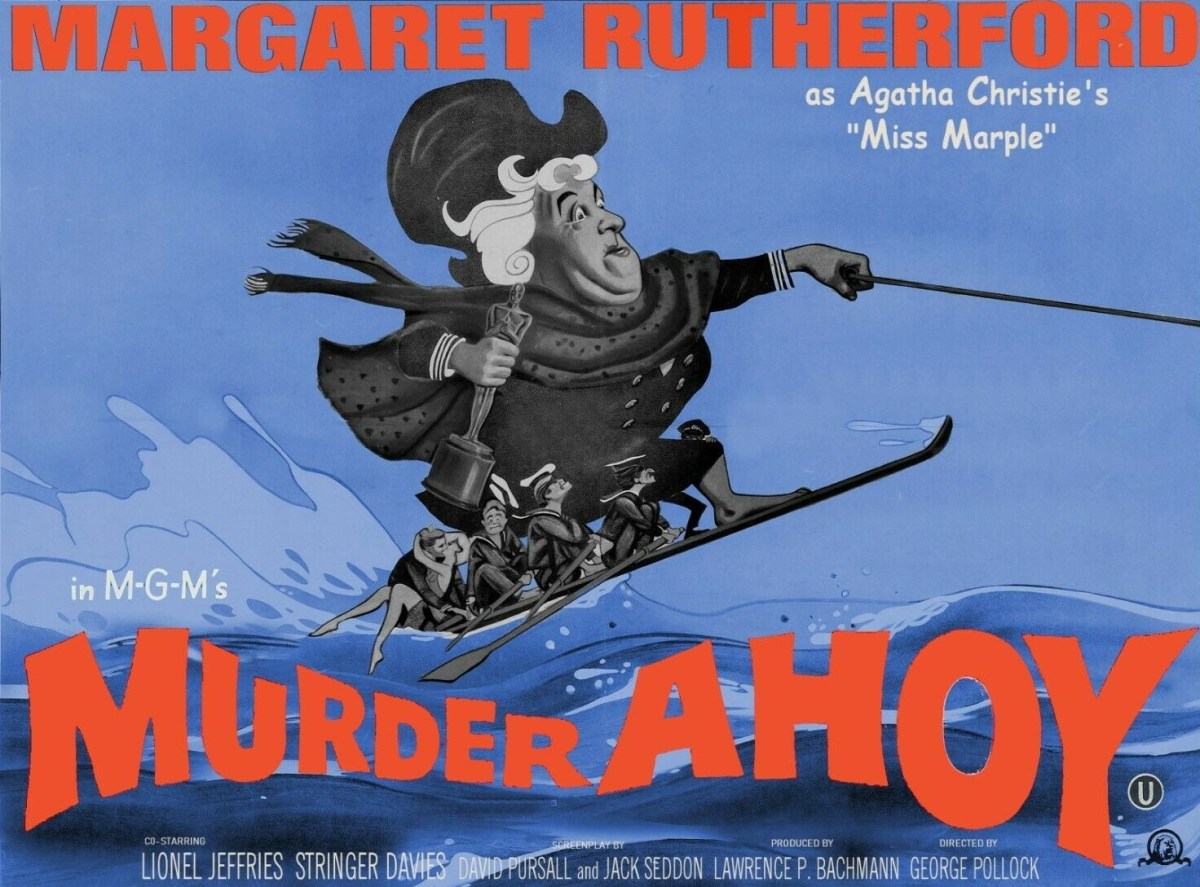

Ambruster is already in cahoots with Inspector Oliphant (Lionel Jeffries) and it’s not long before Gridley is enrolled to act in an undercover capacity, sneaking into her bedroom, finding a gun in a drawer and overhearing suspicious phone calls all the while continuing to romance her. Meanwhile, he’s woken up in the middle of the night with her playing an organ. He’s such a clumsy clot he manages to set fire to a garage, which attracts front page headlines and puts his career in jeopardy.

Anyway, various red herrings later and Ambruster somewhat mollified after falling for Hardwicke’s charms himself, we discover that her husband isn’t missing after all, but when he turns up, she shoots him dead and so ends up in court charged with his murder. His death, while convenient, is treated as accidental.

But the fun’s only just beginning. What could have been a shade close to film noir or the kind of romantic thriller Hitchcock turned out in his sleep, now takes a quite bizarre turn. It transpires that her husband, a thief, has hidden stolen jewels in a candelabra which, because she’s short of cash, she has sold to a pawnshop. This emerges in the aforementioned bathtub contretemps. But Hardwicke is being blackmailed by the witness whose evidence cleared her. Said witness has made off with the jewels and now plans to kill off the real witness. So they all end up at a retirement village in, where else, Penzance. Gridley has to save the real witness from being run off the edge of a cliff in a wheelchair while Hardwicke and the fake witness would have had a real old catfight if either of them could have managed to land a punch, instead of hitting the ground or falling backwards into bushes, so the entire climax suddenly takes a distinct comedic turn.

There’s not even a decent performance from Fred Astaire (The Midas Run, 1969) or Lionel Jeffries (First Men in the Moon, 1964) to lift proceedings. In fact, the best performance comes from villain Miles Hardwicke (Maxwell Reed) who rejoices in lines like, “ I like you better when you’re frightened.”

Written by Larry Gelbart (The Wrong Box, 1966) and Blake Edwards (The Great Race, 1965), which would make you think comedy, and that this was a spoof in the wrong directorial hands, except that Edwards was responsible for Experiment in Terror / Grip of Fear (1962) so knew how to extract thrills.

Coulda been, shoulda been – wasn’t.