Of all the lazy, incompetent streamers this has to take the biscuit. Not content with branding as new films made over half a century ago, now we have films being screened which clearly nobody has bothered to watch even once. Otherwise, how to explain a picture where the language lapses into Italian at critical moments without the benefit of sub-titles.

Which is a big shame because, confusing through the movie is, it takes an unique approach to the femme fatale angle and serves up a noted screen tough guy as one whose heart is genuinely broken – suck that up, pale imitators going by the name of Stallone, Schwarzenner, Willis et al.

Post-Bullitt (1968) but pre-The French Connection (1971) we open with a dazzling car chase where the pursued race up stairs rather than down as is the current trope and batter their way through closely-packed streets in the Virgin Islands. That’s before wannabe retired assassin Jeff (Charles Bronson) is gunned down, although he’s still capable of diving under a burning car to escape immediate detection.

Jeff is on the lam with lover Vanessa (Jill Ireland). Dumped in jail with time to repent (no, strike that), mull over his circumstances, in the meantime dodging a tarantula (a real one!) crawling over his body, and coming to the conclusion that the moll has set him up and has returned to her previous lover, ace racing driver Coogan (no idea who plays him, imdb doesn’t know either). Despite having abandoned his profession, Jeff, not getting the hang of the broken-hearted moping malarkey, decides he’ll come out of retirement for the usual one last job, this time laying waste to Coogan.

But someone spots him and he’s blackmailed by Mafia chief Weber (Telly Savalas) into continuing his murderous ways. But here’s a sting in the tail – a wonderful twist to end all twists: Weber is Vanessa’s husband. She’s not a femme fatale at all just a sexual butterfly who dances from one lover to the next with Weber’s tacit approval.

But, in fact, in another twist, she is, after all, the femme fatale to end all femme fatales, setting up Jeff to bump off Weber so that she and attorney lover (what, another one) Steve (Umberto Orsini), Jeff’s best buddy, can take over her husband’s organization now that it has gone legit. And in the final twist to end all twists this ends with Jeff’s broken heart turning him suicidal (beat that Schwarzenneger, Stallone, Willis et al).

This is a very down’n’dirty Italian thriller, dashing from deadbeat locale to Southern Belle balls, from rusting riverboats to swampland, from factories to fashion shoots, the confusion factor infused further by the sudden incursions into Italian, often in mid-scene, as if this was some kind of artistic coup, determined to leave the viewer baffled.

Despite going the whole nine yards in the broken-heareted department, Jeff isn’t quite the full-blown romantic, an attempted rape of Vanessa in New Orleans only interrupted by (wait for it) three thugs beating another character to death. Naturally, Jeff isn’t the kind of good bad guy who intervenes, and these characters, even more naturally, have nothing to do with the plot (except as Jeff points out it’s a violent city after all). But what the hell, it’s that kind of film.

I’ve cutting Amazon Prime a big break here with my rating, because despite the language problems, it’s a cut above your normal thriller, and Charles Bronson (Red Sun, 1971) before being typecast by Death Wish (1974) gives a very good account of himself, certainly a lot more to do than just grimace, and, heck, you even feel sorry for him twisted inside out by emotion. Telly Savalas (A Town Called Hell, 1971) is a bit more polished and emotionally aware than his usual villain.

You might be tempted to call Jill Ireland (Rider on the Rain, 1970) the stand-out. She still can’t act for toffee, but she is well suited to playing this kind of jinxed minx, whose beauty snags dupes well below her league. And (spoiler alert) she does let it all hang out, indulging in copious nudity.

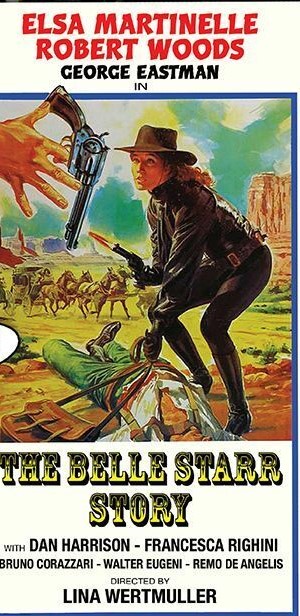

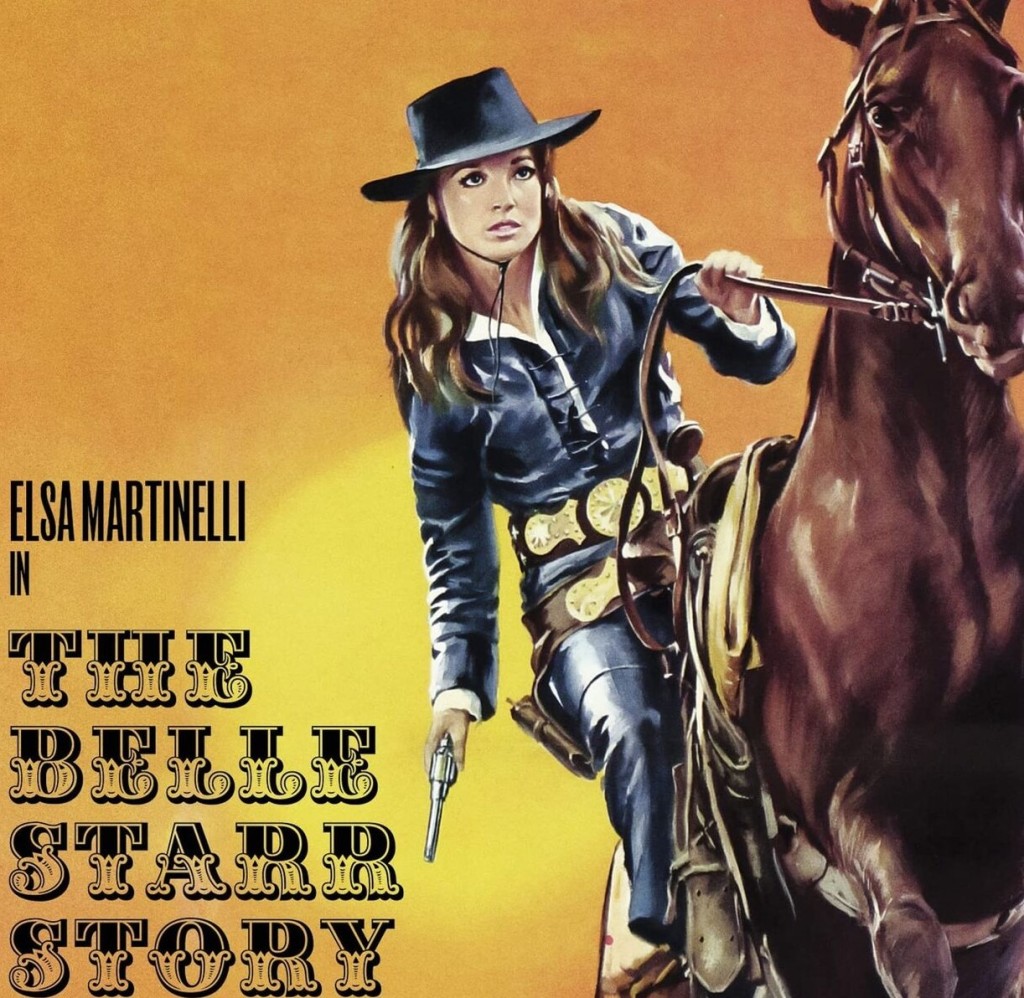

Directed with some flair by Sergio Sollima (The Big Gundown, 1967) and extra marks for coaxing unusual performances from the three principals. Six screenwriters (can’t you tell) put this together including Lina Wertmuller (The Belle Starr Story, 1968). Great score by Ennio Morricone.

Given I couldn’t understand half of what was going on thanks to streamer disinterest in sub-titles, I was still very impressed. Worth a watch.

NOTE: Amazon Prime has this under the title Family but once the credits roll it switches to original title Violent City.

Youtube has the trailer.