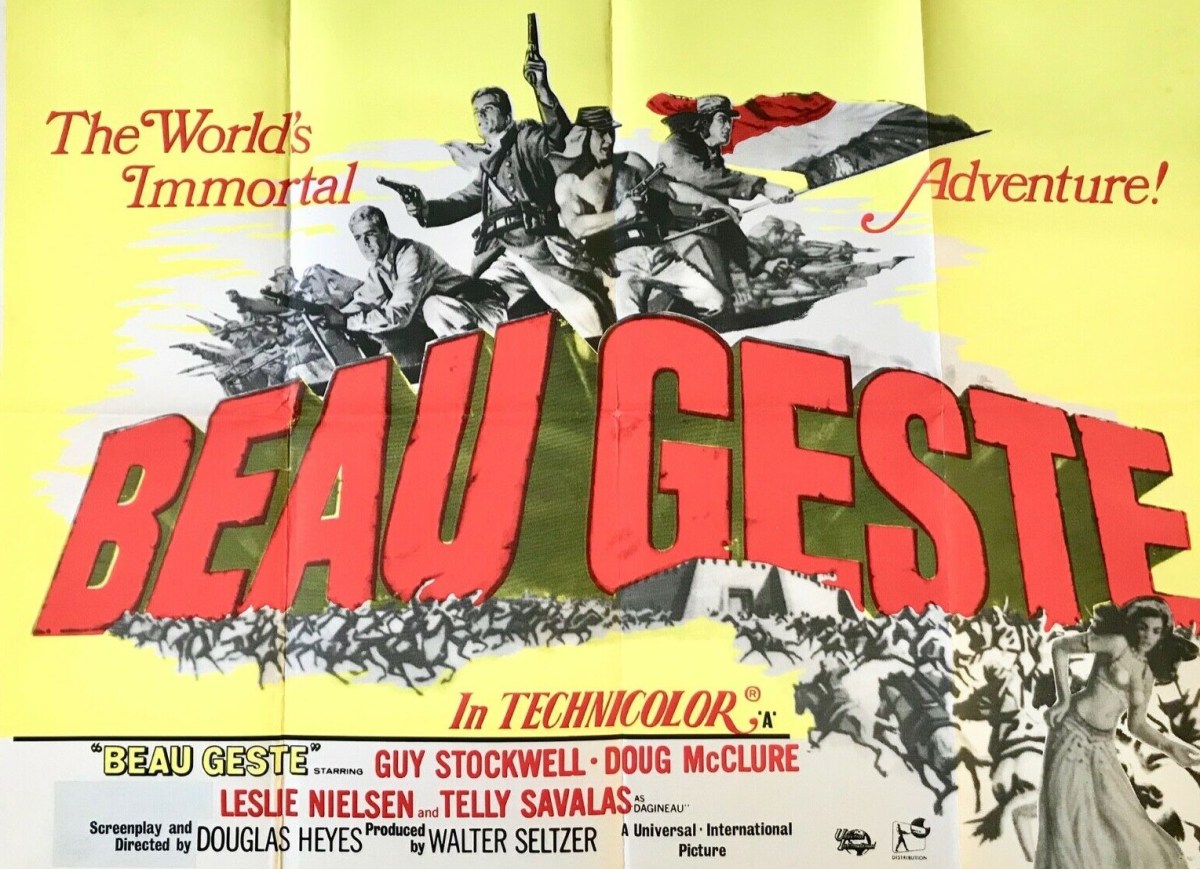

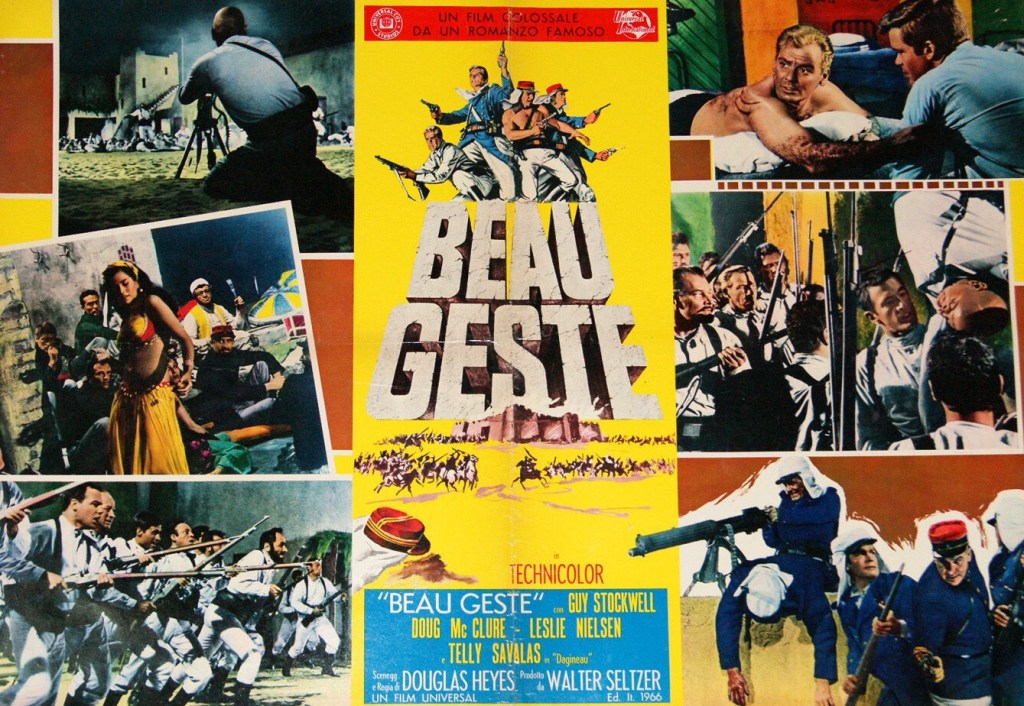

Two brothers battle inhospitable terrain, warring tribes and a sadistic sergeant major in a remake of the classic tale. The title translates as “noble and generous gesture” and is a pun on the name of hero Michael Geste (Guy Stockwell), an American hiding out in the French Foreign Legion in shame for being involved, innocently as it happens, in embezzlement. His attitude is markedly different to the “scum of the earth” who make up the battalion and his quick wit and refusal to kowtow make him a target for Sgt Major Dagineau (Telly Savalas), a former officer busted to the ranks.

Dagineau delights in imposing hardship and devising mental torture, making some recruits including Geste walk around blindfold at the top of a cliff. Geste’s resistance to his superior is almost suicidal and he even volunteers to take a whipping on behalf of his comrades. “It’s me he wants,” says Geste, “if not now the next time.” At another point he is buried up to his neck in the blazing sun.

Joined by his brother John (Doug McClure), the battalion sets out as a relief force for a remote fort but when commanding officer Lt De Ruse (Leslie Nielsen) is seriously wounded, the sergeant-major takes charge. Under siege from the Tuareg tribe, honor, treachery, mutiny, fighting skills and courage all come into play in a final section.

The action and the various episodes and confrontations are strong enough and Geste has a good line in witty retort, but blame the casting for the fact that it turns into Saturday afternoon matinee material. It was always going to be a stretch to match Gary Cooper, Ray Milland and Susan Hayward from the 1939 hit version.

Stagecoach, remade the same year, was able to rustle up a bona fide box office star in Ann-Margret (Viva Las Vegas, 1964) and a host of supporting players with considerable marquee appeal including Bing Crosby (Robin and the 7 Hoods, 1964), Robert Cummings (Promise Her Anything, 1965) and Van Heflin (Cry of Battle, 1963). Nobody in the cast of Beau Geste could compare. Apart from the Spanish-made Sword of Zorro (1963), Guy Stockwell usually came second or third in the credits, as did Doug McClure (Shenandoah, 1965) while Telly Savalas, despite or because of an Oscar nomination for The Birdman of Alcatraz (1962), was viewed as a character actor.

But that was the point. Universal gambled on turning the latest graduates from its talent school into major box office commodities. The set pieces and the action are well handled and while there are excellent lines especially in the verbal duels between hero and villain, it’s not helped by the most interesting character being Dagineau, who, despite his failings, accepted his fall from grace, worked his way back up the career ladder, believing brutality the only way to control the soldiers, and in the end out of the two is the one who has the greater sense of honor, refusing to allow a lie to befoul the truth, rejecting the notion of when the legend becomes fact print the legend, And it’s a shame that the movie has to present his character in more black-and-white terms rather than invest more time in his background or accept his version of reality.

Telly Savalas (The Scalphunters, 1968) steals the show with a performance of considerable subtlety. Guy Stockwell (Tobruk, 1967) is little more than a stalwart, the heroic hero, with little sense of the irony of his situation. Doug McClure (The King’s Pirate, 1967) presents as straighforward a matinee idol. If you only know Leslie Neilsen from his later spoof comedies like Airplane! (1980) you will be surprised to see him deliver a dramatic performance as the drunken commander who still insists, in an echo of El Cid, in rising from his sick bed to lead his troops. Normally this kind of macho movie – The Magnificent Seven (1960) and The Dirty Dozen (1967) prime examples – throws up burgeoning talent who go on to make it big. It’s one of the disappointments here that this does not occur.

This was the second and final movie of Douglas Heyes (Kitten with a Whip, 1964).