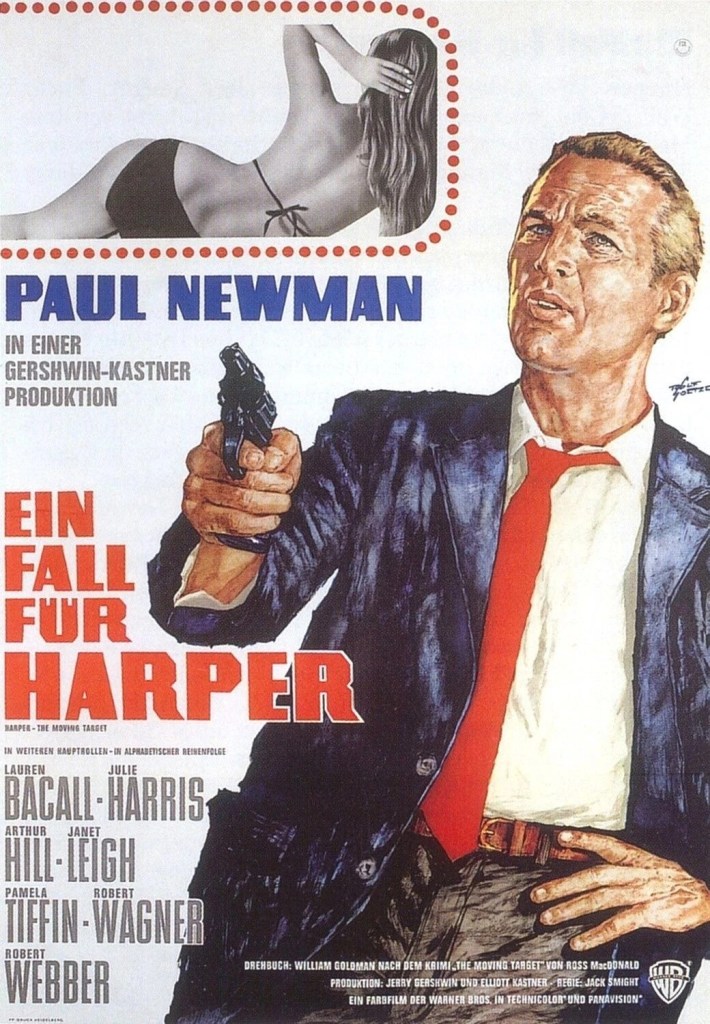

Inventive screenplay by William Goldman (Masquerade, 1965), the ideal combination of witty lines and others that strike to the heart, and Paul Newman’s most naturalistic performance, and a family at each other’s throats, create a genuine addition to the private eye genre. Punch-ups are limited, generally the sleuth comes out worse, his skull an easy target apparently for any villain wanting to give him a good biff.

Most people remember the celebrated credit sequence. But, in fact, most people do not. They remember that this is a guy who will reuse old coffee grinds, which is as good a character definition as you’re going to get. But the opening sequence says much more – he sleeps in a pull-out couch, he falls asleep with the television on, dunking his face in ice suggests a hangover, and – the killer – he sleeps in his office. You won’t forget the ending either, the freeze frame, as fed-up Harper (Paul Newman) just gives up on the stupidity of mankind. And just before that there’s a delicious moment when crippled mother Elaine Sampson (Lauren Bacall) trills to the daughter she loathes Miranda (Pamela Tiffin) in a voice that would denote happiness but is anything but, “I’ve got some news for you,” as she looks forward to informing the child that the father she adores and that Elaine equally loathes is dead.

Not surprisingly, Harper’s on the verge of divorce from wife Susan (Janet Leigh), but he still hankers after being a knight in shining armor, those few days every year when he puts the world to rights rather than chasing down errant husbands in seedy hotel rooms.

The tale is a tad convoluted, involving initially tracking down Elaine’s estranged missing millionaire husband that turns into kidnapping and then murder with a side order of a fake cult headed by Claude (Strother Martin) that’s a front for an illegal immigrant operation, and going through the gears, character-wise, with malicious wife, an extremely flirtatious Miranda who gets her come-uppance when she tangles with Harper, faded alcoholic star Fay Estabrook (Shelley Winters) and junkie Betty (Julie Harris) sometime lover of lothario pilot Allan Taggert (Robert Wagner).

Two distinctive thugs Dwight Troy (Robert Webber) – Fay’s husband – and Puddler (Roy Jenson) offset the dumbest of dumb cops led by Sheriff Spanner (Harold Gould) and lovesick attorney Albert Graves (Arthur Hill), Harper’s longtime buddy, who pines for Miranda.

Torture comes in two guises – the junkie gets the treatment from Dwight and Harper is put through the wringer listening to the endless whining of Fay as he tries to pump her for information. Harper avoids beatings and takes beatings and various characters bounce through doors with a gun – both Taggert and Graves save Harper from being shot.

Harper’s got a slick way about him, but mostly his charm is used to weasel information. He hasn’t got enough of it left to work on his wife.

When Harper’s not racing his sports car along twisting mountain roads, the action shifts to a cult temple, the docks and an abandoned oil tanker. Even when Harper works out who’s in on the kidnapping, it turns out he’s now got a murder to solve since someone’s bumped off the kidnappee.

Despite the endless complications, this whizzes along, helped enormously by Paul Newman’s (Cool Hand Luke, 1967) winning characterization. He’s brought a new trick to his acting arsenal, mastering a method of not listening to a conversation by tilting his head away from the speaker, and there’s a number of novel gestures. The scene where he rejects Miranda is a cracker. Tough guy running short of a soft center, he makes a very believable human being. And he’s got his work cut out because Lauren Bacall (Shock Treatment, 1964) is on scene-stealing duties. As is Pamela Tiffin (The Pleasure Seekers, 1964) though she can hardly match the older woman for arch delivery.

It’s a top-notch cast all the way down. Fans of Strother Martin (Cool Hand Luke) will enjoy his fake healer, Arthur Hill (Moment to Moment, 1966) is engaging, Robert Wagner (Banning, 1967) adds another notch to his rising star bow while Robert Webber (Don’t Make Waves, 1967) emanates menace with his “old stick” routine. Shelley Winters (The Scalphunters, 1968) is a great lush, Julie Harris (The Split, 1968) a junkie trying to pretend she’s not and Janet Leigh (Psycho, 1960), having kicked her husband out, still hoping he might come back in more acceptable form.

Jack Smight (The Third Day, 1965) directs with some zap. This should have had everyone singing the praises of crime writer Ross MacDonald, who in inventing the character (Lew Archer in the original) had inherited the Raymond Chandler mantle, but instead they came away whistling Dixie for screenwriter William Goldman.

Class act.