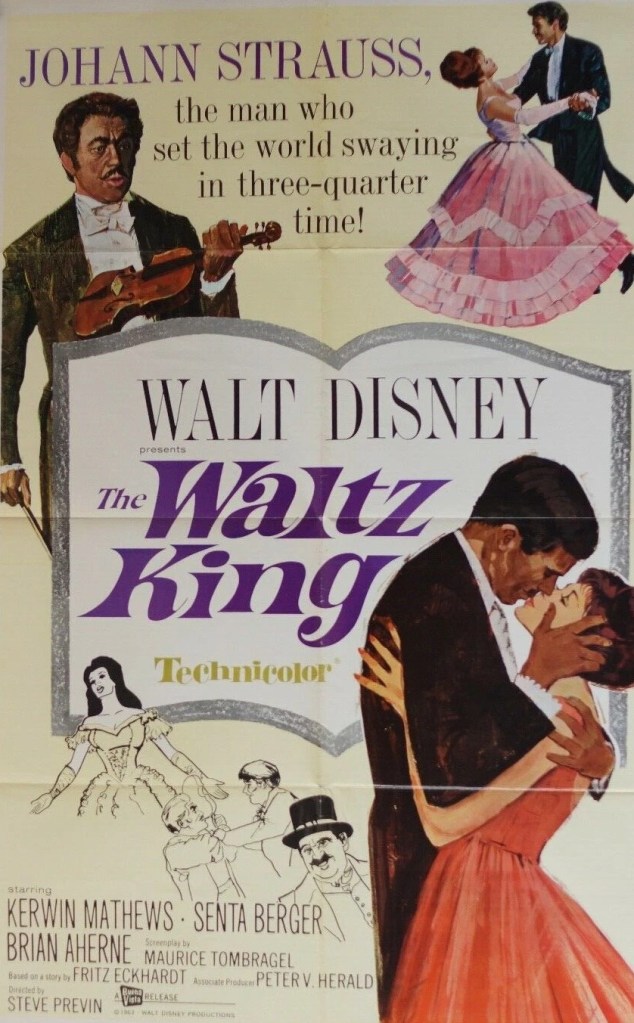

The Twist, the Macarena, Twerking, none of these routines can hold a candle to the Waltz, which has dominated the dance world for centuries. You think maybe Queen invented the idea of audience participating in a tune by dancing and clapping in “We Will Rock You”, well, that had been an integral element of waltzes with a faster rhythm equally for centuries.

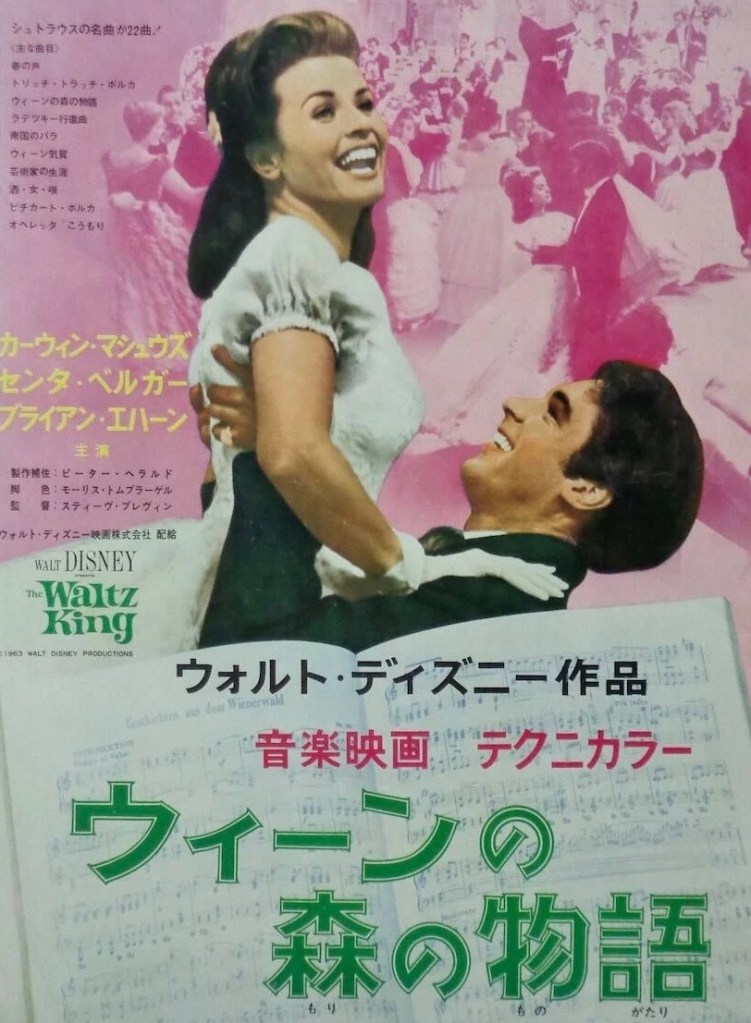

The movie had an unusual trigger. Walt Disney, taking time out from overseeing theme parks and enjoying a period of dominance in Hollywood, had spent some time in Vienna which resulted in this film and the same year’s Miracle of the White Stallions about the World War Two escapades of the Spanish Riding School in Vienna.

As you know I am a conscientious researcher in the matter of Senta Berger Studies and came to this via that connection, but I have always enjoyed movies about creativity whether it is struggling writers, struggling painters, struggling sculptors and struggling composers – you notice the prefix “struggling” is an essential component of such films.

And this will chime also with a contemporary obsession – the nepo baby. There already was a Waltz King in Vienna – Johan Strauss’s (Kerwin Matthews) father (Brian Aherne) also called Johan. He didn’t want this son following in his footsteps not so much because he feared the competition but because he disdained his own work, being at the beck and call of greedy concert promoters and music publishers, being assailed by hundreds of female fans behaving in much the same way as female fans during the rock/pop era, though instead of throwing underwear onto the stage they were apt to bombard the composer with bouquets of flowers each delivered with a note expressing ardent passion.

Father Johan Strauss (known to classical music fans as Johan Strauss I) insists son Johan Strauss ( Johan Strauss II in the classical music business) enter a proper profession, one where position in society was not dependent on the whims of the public. So the young lad was forced to become a lawyer, moonlighting as a violinist with other orchestras hoping his father would not find out. When old man Strauss did find out he was apt to take strenuous action and destroy the young man’s violin.

The elder Strauss was so powerful in his field that music publishers did not dare take on any of the works of his son. So it was lucky that in order to persuade a music publisher to listen to his composition he sits down at a piano in the shop and begins to play at the same time as opera singer Henriette Treffz (Senta Berger) is present. She likes the music and takes a shine to Johan and coughs up so he can employ his own orchestra.

The old man is so angry at being usurped that he conspires to wreck the son’s debut concert by employing a small army of people to hiss, boo and catcall and disrupt the event. Luckily, that plan fails and audiences applaud and the son is on his way. Paternal enmity continues but that matters less as Johan Strauss II becomes a brand name, although he’s subjected to the by-product of fan mania when jealous husbands threaten him with a duel.

But just as The Who and other bands aspired to something more than popular music, so Johan wanted to move beyond the simplicity (in musical terms) of the waltz and up the classical music hierarchy by putting his mind to creating operettas and more sophisticated tunes. That battle involved finding his own voice and once again overcoming opposition.

This being a Disney confection it skirts over politics. Father and son were on opposite sides during the failed Austrian Revolution of 1848 – Strauss Snr composing one of his most famous pieces, the Radetsky March, as a result, the son out of royal favor for a long time. Nor is there time to regale audiences with how Strauss Jr changed his religion to get out of a tricky second marriage.

But like most biopics about classic composers including such Oscar-acclaimed fare as Amadeus (1984) this is a jukebox piece and if nothing else takes your fancy you can sit back and listen to the Johnan Strauss II’s greatest hits which include “The Blue Danube Waltz,” Die Fledermaus and Tales from the Vienna Woods.

Kerwin Matthews (Maniac, 1963) is solid enough in role that in a Disney picture requires less than the likes of Amadeus. And anyway he makes the mistake of signing on for a picture with Senta Berger (Kali-Yug, 1963) who is at her dazzling best. Brian Aherne (Lancelot and Guinevere, 1962) almost twirls his moustache as villain of the piece.

Director Steve Previn (Escapade in Florence, 1962) does a decent enough job with the music an eternal get-out-of-jail-free card. Written by Fritz Eckhardt (Rendezvous in Vienna, 1959) and Maurice Trombagel.(Monkeys, Go Home!, 1967).

Lightweight, for sure, but entertaining and informative enough.