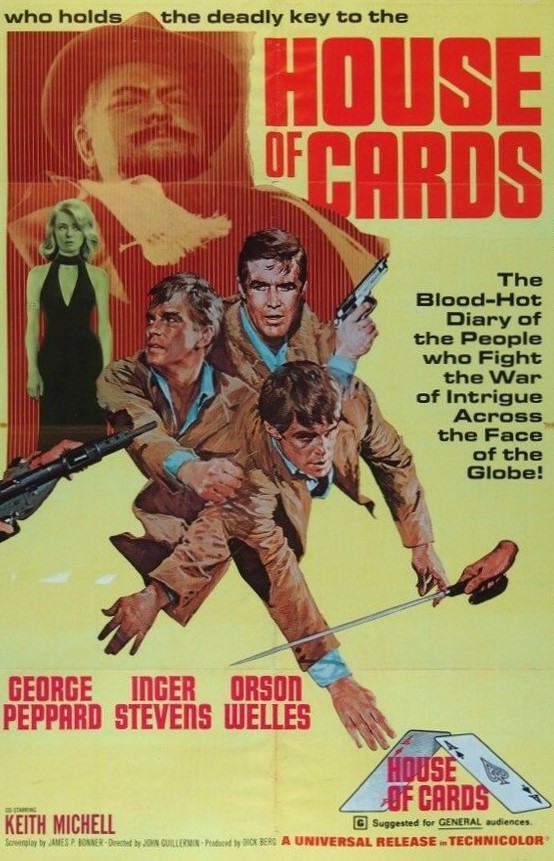

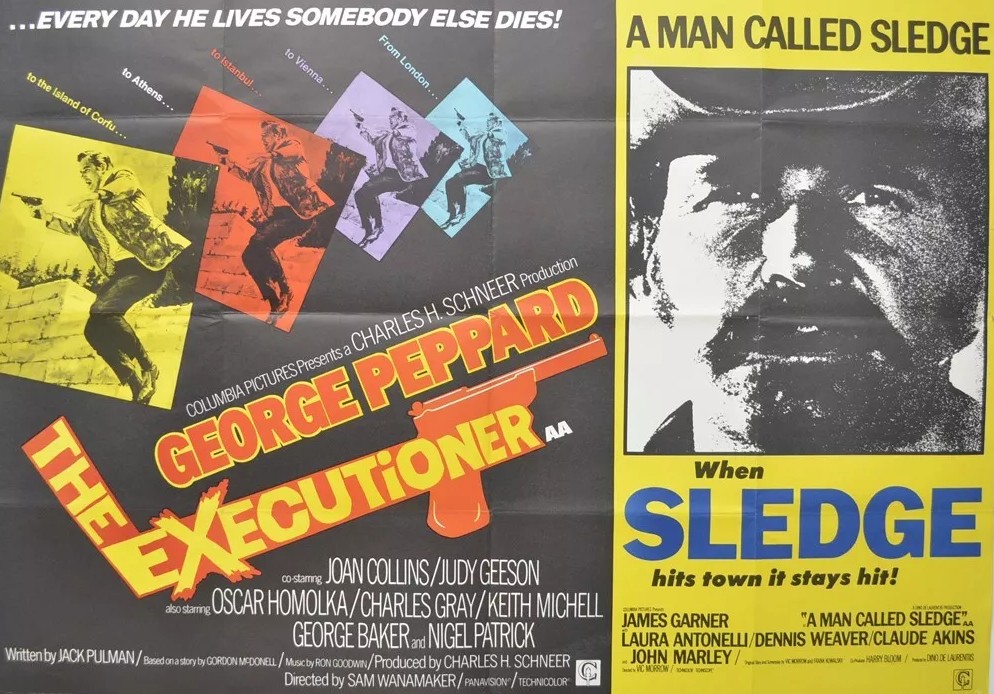

Minor gem. One of the espionage films of the era ignored by audiences because it lacked the verve of James Bond, no car chases or bedhopping hero to maintain interest when the narrative stretched credulity. Ignored by critics because it starred the vastly underrated George Peppard. Yet if you wanted an actor to show pain, to suffer from humiliations to his dignity, there was no one better, in part because on screen (and apparently in real life) arrogance was key to his persona. Here, you can add confusion to that mix of unwelcome emotions.

Beginning a scene with the aftermath of slaughter has become a modern thriller trope – see The Equalizer 3 (2023), The Accountant 2 (2025) for the most recent examples – but this is where the idea began and it’s how this picture opens, the only survivor of the massacre being the wife Sarah Booth (Joan Collins) whom our hero John Shay (George Peppard) covets. An immediate flashback shows them consummating their love. So you’re guessing there’s something of the James Bond in Shay, carrying on an illicit love affair.

But in fact that’s just one of the clever titbits of misdirection director Sam Wanamaker (The File of the Golden Goose, 1969) throws our way. And, gradually, we realize this is not so much about dirty dealings in the espionage business, the usual hunting down of a double agent, our hero clashing with disbelieving and frosty upper class bosses, but more about how the flaws in human nature turn characters inside out.

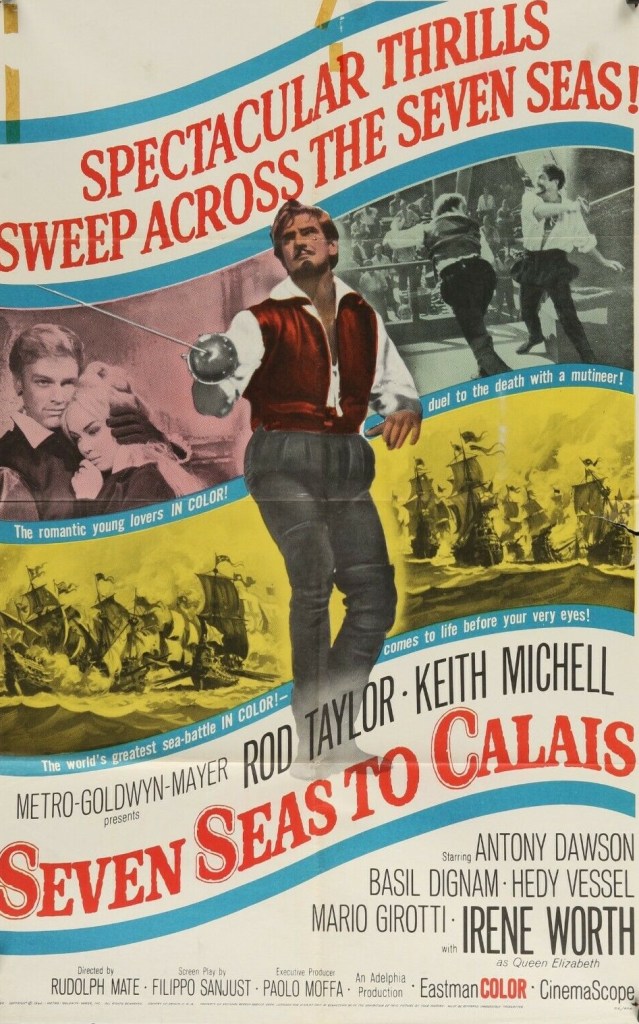

It’s no surprise that Shay is an outsider, not with that American accent standing out a mile in the British secret service run by the cut-glass accents of the likes of Col Scott (Nigel Patrick) and Vaughn Jones (Charles Gray). He’s not a member of the club, old boy. He bristles at not belonging – “belong to me!” wails girlfriend Polly (Judy Geeson). And he’s been passed over by love of his life Sarah for another agent Adam Booth (Keith Michell) not because the latter has wealth and status but because Shay’s mind is too often elsewhere.

Though you are initially led to believe that Shay is having an affair with Sarah, that turns out to be far from true, although the glances he casts at her are enough to make Polly think they still are. And part of the reason his superiors distrust his assertion that Adam is a double agent is because they think he just wants rid of his rival so he can make another play for his former lover.

Shay is so convinced that he is right that he gets Polly, who also works in the secret service but in the backroom department, to sneak out top secret files. When he stitches up enough information to make the case against Adam, it backfires and he’s suspended. But then, egged on by a discovery by top boffin Crawford (George Baker) working on some top secret stuff, he decides to kill Adam and chuck the body out of a plane into the English Channel – hence becoming the executioner of the title.

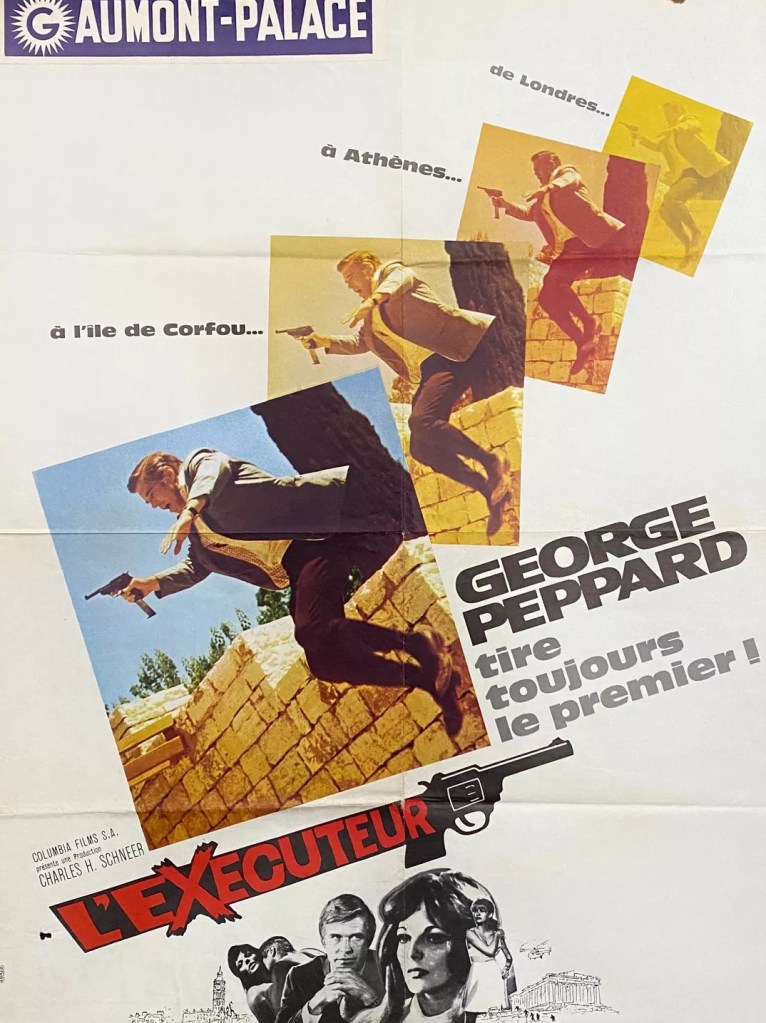

Then the twist is truly in when Shay takes Adam’s place on a mission to Greece, which has also been planned as a second honeymoon for Adam and Sarah. This latter fact doesn’t dissuade Shay from making a romantic play for Sarah. However, there are nefarious dealings afoot espionage-wise but in what proves the first of many miscalculations Shay comes unstuck and is beaten up by the opposition and Sarah kidnapped. The ransom the Soviets demand is Crawford.

The massacre that we saw at the start solves that problem.

But it turns out Shay has let desire for Sarah muddle his brain for Adam was not a secret agent. Shay has been further duped into that belief by Crawford who also has romantic designs on Sarah, though it has to be said in her defense that Sarah has encouraged neither of these potential suitors.

There is one final twist but that’s just another nail in the coffin.

So what sets out to be a different kind of spy thriller turns into the polar opposite of what audiences might have expected, playing more on the human frailty of the hero than hitherto in the genre.

George Peppard is excellent, especially when expressing emotional pain and confusion, continuing a superb run of acting roles – ignored by the critics of course but tossing his screen persona away – that ran from Rough Night in Jericho (1967) and P.J. (1967) to Pendulum (1969). Judy Geeson (Brannigan, 1975) has the better female role as the disgruntled but faithful girlfriend. Aside from the occasional acidic remark, Joan Collins (Subterfuge, 1968) is strictly there for the glamor. Written by Jack Pulman (Best of Enemies, 1961) from a story by Gordon McDonnell (Shadow of a Doubt, 1943).

Well worth a look.